With limited prospects for growth, one of the iron laws of economic downturns is that advertising is among the first budgets to be cut.

Advertising revenues have already cratered at many alt-weekly newspapers, which heavily rely on local events and restaurants that have been shuttered in the wake of the COVID-19 outbreak. BuzzFeed even went so far (as they do) to label it a “media extinction event.”

Clearly it’s bad times, but I wanted to get a lot more granular around the data for ad rates, particularly around top startups. So I compiled a list of a little more than 100 unicorns across a variety of sectors and explored how the prices of their search engine keywords have changed with the global pandemic that is sparking a global recession.

The results aren’t surprising — there has been a collapse in prices for almost all ads (with some very interesting exceptions we will get to in a bit). But the variations across startups in their online ad performance says a lot about industries like food delivery and enterprise software, and also the long-term revenue performance of Google, Facebook and other digital advertising networks.

A quick overview of the data

It’s common for startups to buy their own keywords on search engines like Google and the App Store. Owning that top rank guarantees that their own company’s page is the first result a user sees and prevents competitors from buying their name, potentially intercepting customers.

For this analysis, I selected more than 100 United States-based startup unicorns; using Google Search, Google Keyword Planner and, at times, prodigious patience, I collected information on the ad rates and performance for each startup’s name as well as who was advertising on it.

Searches on Google for ad placement were based on desktop Safari and were conducted from New York City in English. Google uses a variety of signals to calculate its search engine results — including ads — and the experience of users using other browsers and in other geographies may be radically different.

Even in this economy, startups are buying their own names

The first thing I investigated was whether when searching for a startup, that startup had purchased an ad for its own search query. My analysis shows that 49 of the 103 unicorns I investigated bought the ad placement for the names of their own startups, or just shy of 50%.

The startups that did and did not buy their names spanned all verticals and industries, and there didn’t seem to be any particularly specific pattern to this activity. In consumer, Airbnb was still buying its own query on Google, while Warby Parker was strangely absent from my search. Fintech startups like SoFi, Stripe, Brex and Robinhood (and others) mostly bought their own names, as did most enterprise startups like Snowflake, Airtable, Confluent and Gusto.

There were a couple of surprises. Coursera wasn’t purchasing its name, even though work from home is in full effect and it would seem to me to be an obvious buyer right now, given the demand for online courses. Toast was still purchasing its name, despite the fact that it operates a point-of-sale system for restaurants that have been ravaged by the shut down of many public establishments.

One interesting dynamic though is that companies are not bidding for their competitors’ names very frequently. Out of 103 companies, only 13 had ads placed from competitors in my searches.

Some interesting data materialized here. Only one search — for Monday.com and Asana — had competitors bidding for each other’s keywords, with Monday.com also having an ad from Smartsheet on its SERP (search engine results page). Meanwhile, Postmates isn’t advertising on its own keyword, but direct competitor Uber Eats is. Over in the enterprise space, DevOps platform GitLab wasn’t advertising for its keyword in my search, but CircleCI was. Finally, erectile dysfunction startup Hims bought its query in direct competition from Roman and Keeps (perhaps some truth to the theory that there will be a coronavirus baby bump in nine months).

Despite the fact that almost all of these unicorns are in competitive markets, very few seemed to be facing competition to buy their ad space, which is surprising, given how cheap the numbers are (as we will now see).

Unicorn keywords have fallen off a cliff

Let’s start with some disclaimers and nuances about ad rates in SEM (feel free to skip a bit if you’re an expert here). Google and most SEM networks operate on an auction model, in which higher bidders for ad space are more likely to see their ads selected for placement. For any keyword, spending more dollars per placement generally guarantees more impressions.

Given the options that most search engines offer for choosing an audience, there are almost infinite combinations you can select to optimize exactly the person that sees your ad and what price you want to pay to reach that audience with that query. The ad rates discussed here are generalized and are just that — they don’t necessarily show sub-audiences that might be highly lucrative that would be missed by these general overviews.

Now, all that said, let’s look at some interesting notes from the data I collected.

I looked at the historical range offered by Google for typical CPMs (cost for 1,000 impressions) for ads and compared that to what an ad buyer could purchase prospectively in April. Overall, the general price for ad space against these unicorns has stayed the same for about half of the 103 startups I looked at, but for the other half, ad prices have declined, in some cases by massive proportions.

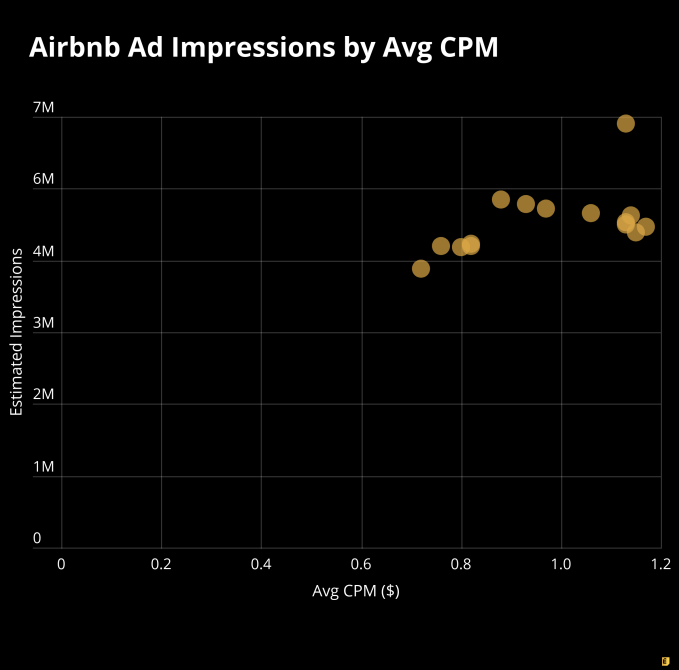

Among the biggest collapses was around Airbnb, which is in the thick of one of the greatest slowdowns of tourism of all time and is clearly not a keyword anyone targeting tourists or hosts are looking to reach anymore. Take a look at this chart, which shows the average CPM against the expected traffic as reported by Google Keyword Planner:

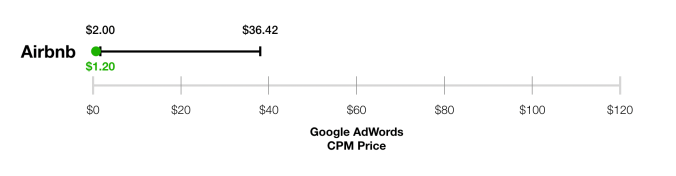

Let’s take an average CPM of $1.20 and compare that to Airbnb’s historical range as reported by Google:

Right now, you can buy millions of “airbnb” page views on Google for essentially pennies, far below historical norms.

Now, as with most travel advertising, many of the keywords that advertisers target are about destinations or particular modes, such as “flights to Scotland” or “hotels in Miami.” Yet, the fact that neither Airbnb nor its competitors are pushing the price of its own query up is an insightful vignette into the challenging times facing the tourism industry.

Let me move on to another example… ezCater does corporate catering — and perhaps understandably, there is much less demand for catering when everyone is working from home. Even so, the company and its competitor Cater2.me were both advertising when I did my searches earlier today, perhaps indicating that even in a challenging market, the low prices for Google Ads are still attractive. Google puts the company’s historical range for average CPM at $3.39 to $92.23, and today, you can get the CPMs at the very low end of that range.

Another category that has seen prices drop precipitously is small-business-serving unicorns like website-builder Squarespace and lender Kabbage, which also saw huge declines in advertising directed at their keywords. Kabbage’s historical range has been around $16.00 to $54.36, but again, you can pull in 1 million page views on that keyword today for around an average CPM of $12.

What causes ad rates to drop? Obviously demand from advertisers, but it can also include the keyword bringing in lower-quality traffic. For instance, if most people searching for Airbnb or ezCater are coming to cancel their orders, then others won’t want to advertise to try to attract that user.

Finally, there is some bright news, at least for Google’s performance. Some keywords are actually getting a bit more expensive, including for Flexport, Checkr and Fair. Those perhaps make sense — Flexport handles global shipping and logistics, which is obviously a stressful point for many companies. Meanwhile, Checkr does background checks for employees, and given the turnover we are seeing in the labor force, more background checks will have to be conducted. Used-car marketplace Fair may be getting popular because a downturn often pushes families to consider their vehicle options (even more so now that shelter-in-place is the order of the land for half of Americans).

Some final thoughts on ad placement competition

I want to do one final bit of analysis here. Google also offers a “competition index” from 0 to 100, which is the percentage of ad slots filled by the number of ad slots available. In other words, when Google offers supply around a keyword, does anyone pay to take it?

Among the 100+ unicorns I looked at, only two had scores of 100 on Google’s metric: Hims and Away, the smart luggage company. A couple of others, including Toast, 23andMe and Kabbage, also had fairly competitive keywords.

What was surprising, though, was how many company names faced almost no competition at all. HashiCorp (whose funding I wrote about recently), Nextdoor, Palantir and Affirm all had almost no competition for their keywords. I don’t want to over-analyze the data — it’s just a sketch of what’s going on — but clearly there are few to no competitors looking to try to grab some eyeballs.

So what’s the takeaway? Clearly some of the most competitive startups are facing a lot less competition, at least in the search engine ad market. Rates remain quite low for many top unicorns, and while almost half are paying to buy their own name, clearly their competitors are less inclined to spend money these days on capturing the attention of those users. All of which is to say that the economic dislocation underway right now portends huge changes for the strategies around search engine marketing.

Comment