Newly released documents reveal Immigration and Customs Enforcement is tracking and targeting immigrants through a massive license plate reader database supplied with data from local police departments — in some cases violating sanctuary laws.

The documents, obtained by a Freedom of Information lawsuit filed by the American Civil Liberties Union and released Tuesday, reveal the vehicle surveillance system collects more than a hundred million license plates a month from some of the largest cities in the U.S., including New York and Los Angeles, both of which are covered under laws limiting police cooperation with immigration agencies.

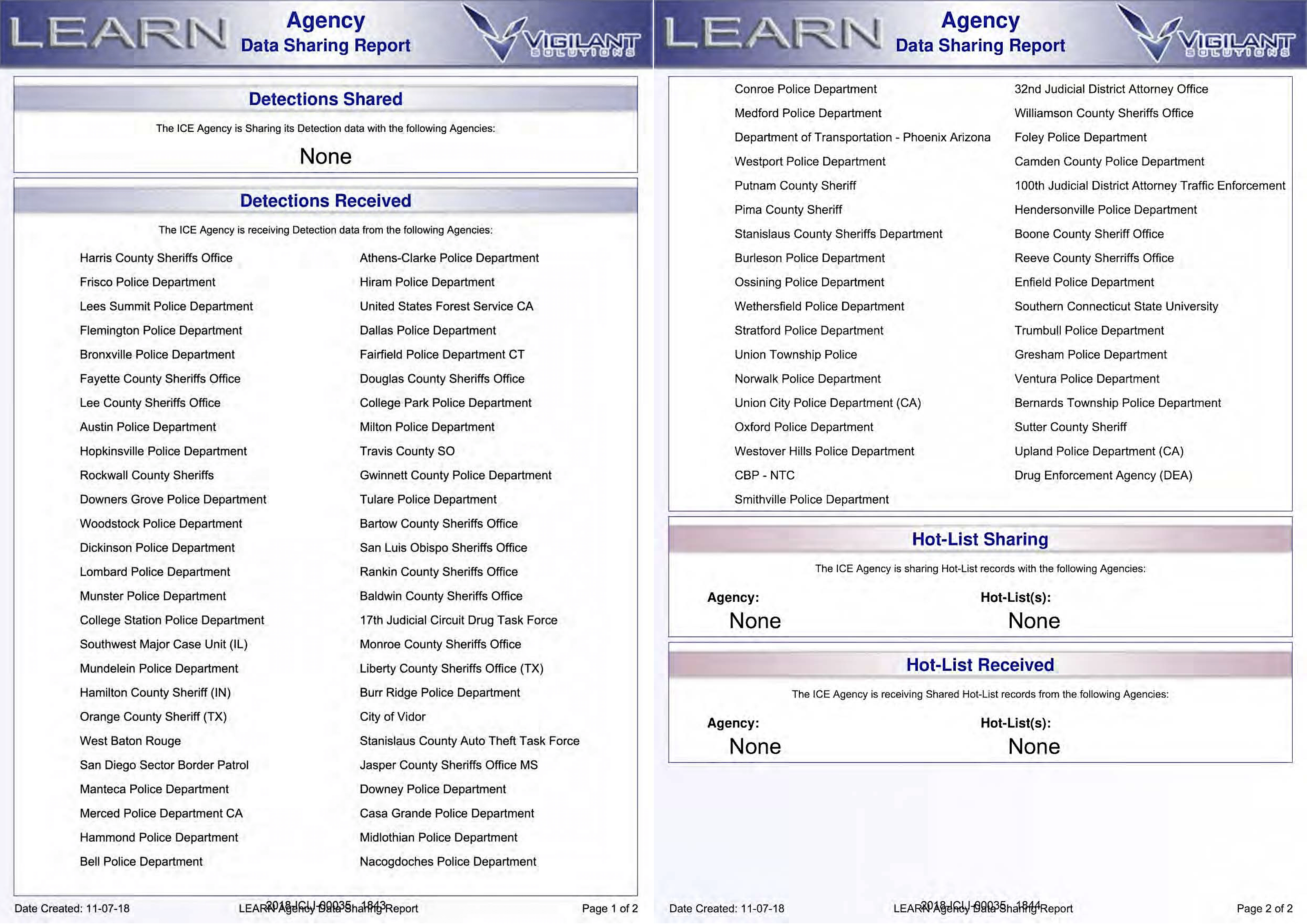

More than 9,000 ICE agents have access to the database, run by Vigilant Solutions, feeding some six billion vehicle detection records into Thomson Reuters’ investigative platform LEARN, to which police departments can buy access.

“The public has a right to know when a government agency — especially an immoral and rogue agency such as ICE — is exploiting a mass surveillance database that is a threat to the privacy and safety of drivers across the United States,” said Vasudha Talla, staff attorney with the ACLU of Northern California, in an email to TechCrunch.

Talla, who sued ICE to release the documents, said the government “should not have unfettered access to information that reveals where we live, where we work, and our private habits.” Critics have noted several high-profile cases of police misusing and improperly accessing license plate data.

Automatic license plate readers (ALPR) scan and detect license plates, along with the time, date and location from thousands of cameras installed across the country to spot criminals and fugitives with warrants out for their arrest. The ACLU previously called it one of the new and emerging forms of mass surveillance in the United States. Companies like Vigilant feed data collected from ALPR cameras into databases accessible to law enforcement and federal agencies, which the ACLU accused ICE of using to find and deport immigrants.

ICE has a “hot list” of more than 1,100 license plates of suspects, felons or other subjects of interest, according to the documents released. Plates on the hot list trigger an alert to ICE that the vehicle has been spotted, including where and when.

“Hot lists are just one method by which ICE agents can track drivers with this system,” said Talla.

ICE spokesperson Matthew Bourke said the agency does not break down how many hot list detections led to deportations or removals from the U.S.

Thomson Reuters spokesperson Jeff McCoy declined to comment. Vigilant Solutions did not respond to a request for comment.

It’s the third effort by ICE to secure access to the database in the past five years, after earlier attempts in 2014 over privacy concerns and 2015 over price negotiations failed. The agency rushed to secure the contract before a planned hike in cost by Thomson Reuters toward the end of 2017.

ICE spent $6.1 million on its latest contract in February 2018, gaining access to 80 law enforcement agencies covering almost two-thirds of the U.S. population. To allay fears of potential misuse, the agency was required to pass a revised privacy impact assessment explaining how ICE can and cannot use the license plate data. In one released email to an NPR reporter, ICE said agents “can only access data” uploaded by police departments if they elect to share it through the system.

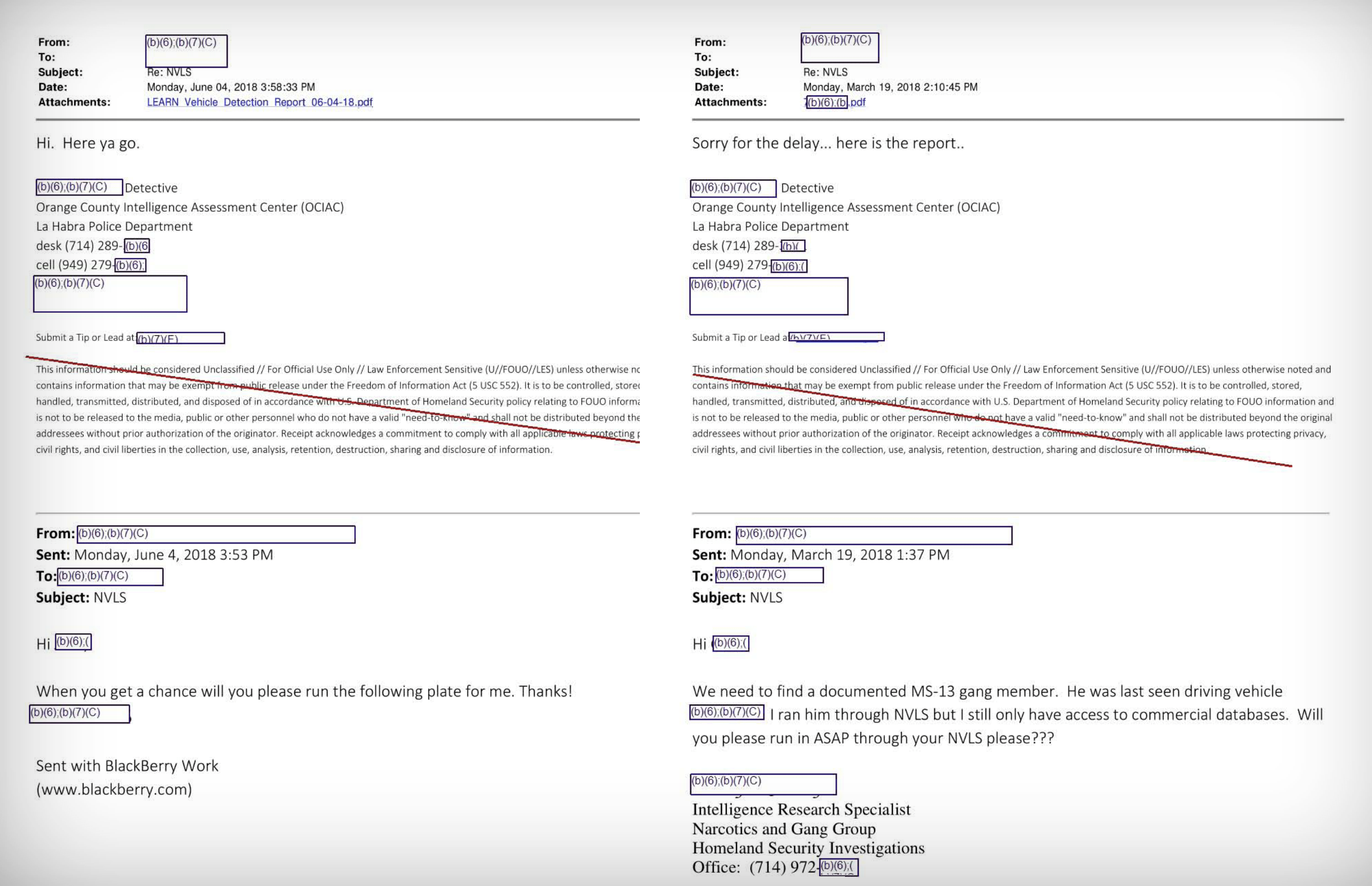

But the ACLU found emails of ICE agents directly contacting local law enforcement officers to ask for license plate search data, circumventing the database.

Over a years-long effort, one ICE agent — whose name was redacted by the government — sent several requests to a La Habra police detective by email asking for license plate data.

La Habra is one of 169 police departments in California, and is one of dozens of departments known to use ALPR. But the city’s police department is not on Vigilant’s list of law enforcement partners that supply license plate data to ICE, the documents show.

We asked La Habra Chief of Police Jerry Price if turning over records to ICE was in violation of California’s sanctuary status, but he would not comment.

“By going to local police informally, ICE is able to access locally collected driver location data without having to ask for formal access to the local system through the LEARN network, which could trigger local oversight or concern,” said Talla.

Other police departments were named as partners that actively feed data into the ICE-accessible database, like Upland, Merced and Union City — three cities in California, which in 2018 passed state-wide laws that offer sanctuary to immigrants who might be in the country illegally or otherwise subject to deportation by ICE. The laws prohibit law enforcement in the state from sharing of license plate data with federal agencies, said Talla.

When reached, Union City Police Department chief Victor Derting did not comment. Spokespeople for Upland and Merced police departments did not respond to a request for comment.

The ACLU called on the immediate end to the license plate information sharing.

The documents also revealed how ICE initially considered trying to keep the database a secret, arguing that disclosing the capability would “almost immediately diminish its effectiveness as a law enforcement tool.”

Amid a controversial and questionable national emergency declared by the Trump administration, ICE remains a divisive agency more than ever. Last year, 19 of the top ICE investigators that investigate serious criminal cases, like drug smuggling and sex trafficking rings, called on the government to distance their work from ICE’s enforcement and removal operations unit, which investigates immigration violations and handles deportations.

In January, TechCrunch revealed dozens of ALPR cameras are still exposed on the internet — many of which are accessible without a password.

Updated with Thomson Reuters’ decline to comment

Smart home tech makers don’t want to say if the feds come for your data

Comment