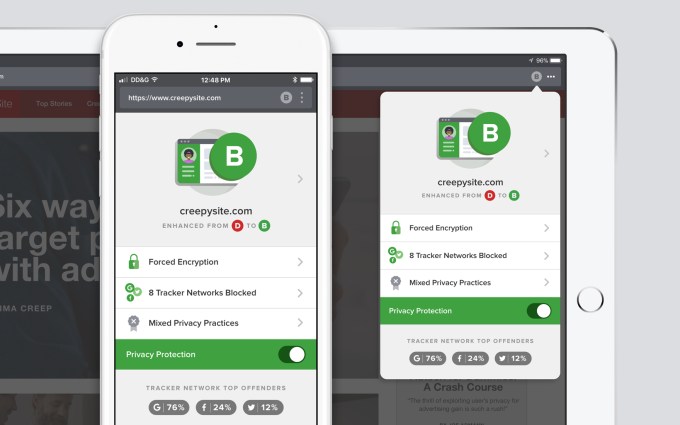

Some major product news from veteran anti-tracking search engine DuckDuckGo: Today it’s launched revamped mobile apps and browser extensions that bake in a tracker blocker for third party sites, and include a suite of other privacy features intended to help users keep surfing privately as they navigate around the web.

The apps and browser extensions are available globally for Android, iOS, Chrome, Firefox and Safari as of now. (DDG tells us Opera is also on its radar but there’s no launch date yet.)

“Our vision has been to set the standard of trust online,” says CEO and founder Gabe Weinberg, discussing the new products. “[To date] we’ve been really focused on the search engine because it’s really complicated to compete with Google in their core market. But now that we feel we can handle that we are making progress on this broader vision of protecting people across the Internet.

“What we’re really trying to do is move beyond a search box… What we realized from talking to people, especially over the last two years, is that privacy risks have gone completely mainstream.

People really want a mainstream, simple solution for privacy.

“People really want a mainstream, simple solution for privacy.”

DDG’s aim is to create a ‘use anywhere’ privacy tool that combines access to its private search engine with tracker blocking and a bundle of other “privacy essentials” — such as an encryption protection feature that automatically sends a user to an encrypted version of a website (if there is one), instead of accepting a default non-encrypted version.

Also new: DDG is serving up a privacy rating for each website visited. This grade is based on how many hidden trackers a site is deploying; whether it’s encrypting your connection; and also considering the site’s own privacy policy (for the latter activity DDG is partnering with terms of service rating initiative, ToS;DR, but also notes that “most privacy policies still remain unstudied” so says it’s going to be helping that organization rate and label “as many websites as possible” too).

“The unfortunate reality is that hardly any sites really deserve an ‘A’ on privacy,” says Weinberg on this. “We can get most sites up to a ‘B’ if we can… block all the trackers and get encryption. Then the gulf between the ‘B’ and the ‘A’ is actually their privacy policies.

“Unfortunately… even if things are blocked and encrypted then the site itself can still collect data as a first party and sell it. And so to really get an ‘A’ rating the privacy policy needs to be vetted.”

For tracker blocking, he says DDG is using some technology from EasyList and Disconnect but also “running through our own tests to try to add to that, as well as make it so that less websites break when you use it”. (To be clear, it’s not doing any ad-blocking; it’s just blocking third party trackers.)

Weinberg claims the tracker blocker is “very effective now”, leaning on the open source community’s expertise, but says DDG also wants to build on the tool and add more privacy and blocking technologies over time — suggesting, for example, a feature that could thwart hidden cryptocurrency miners, which can get embedded on websites, as something else he’d like to add in future.

Asked how DDG’s approach stacks up compared to Mozilla-backed private search browser Cliqz, which last year acquired the Ghostery anti-tracker tool so is playing in a pretty similar space, Weinberg argues the rival product isn’t “really integrated”. “They’re more going after a pure browser situation whereas what we’re saying is, anywhere you are, on any device or major browser, we can augment it to help protect your privacy there in a seamless way,” he says.

“In general, I think that privacy is mainstream and people want simple, seamless solutions and they just don’t exist — until now,” he continues, adding: “We expect most of our search engine users to accept and use the extension and the app because it really extends their privacy protection.

“And beyond our user base, I think this is something that all consumers could benefit from — so we’re hoping that it gets downloaded widely.”

DuckDuckGo has been profitable since 2014, according to Weinberg. (It makes money not by tracking and profiling its users, as Google does, but by serving ads based on the search terms being used at the point of each search, and also from affiliate revenue.) Hence now feeling flush enough with cash to work on expanding beyond the core private search offering.

Last year DDG’s search engine served up just under 6BN private searches — with usage up around 50 per cent on 2016 levels. (Given it doesn’t track individual users it can’t really break out firm user metrics but Weinberg says third party estimates peg users at around 25M at this point.)

On the growth point, DDG says that over a third (36%) of all searches ever entered in its ten-year lifespan were conducted in 2017 alone. So the usage spike it got in 2013, after NSA whistleblower Edward Snowden’s revelations about government mass surveillance programs, has evidently turned into some sustained momentum.

tl;dr, privacy isn’t just a passing fad. Because mass surveillance isn’t just a government activity. The commercial web is lousy with trackers and data brokers too — and Weinberg argues web users are increasingly waking up to how they are being stalked around the Internet.

“In the last couple of years mainstream people have really opened up to the idea that the Internet’s pretty creepy out there — and it’s in large part due to Google and Facebook,” he says. “And in particular that they’re amassing unprecedented amounts of personal information on each person.”

The pair’s use of online tracking for online profiling to power their respective hypertargeted advertising platforms is “at best, annoying”, argues Weinberg, “and at worst causing major political upheavals, like the Russian ad interference” (such as in the US election and the UK’s brexit referendum, to name just two examples on that front).

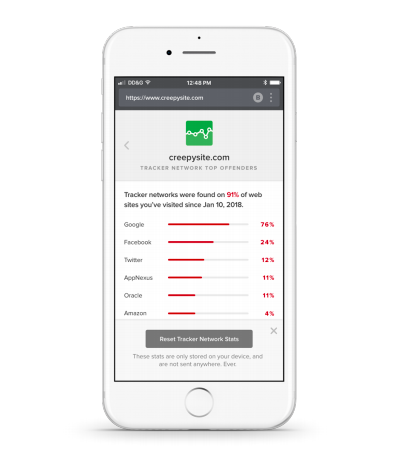

He cites figures that trackers used by Google are now on 76% of the top million websites and Facebook’s trackers are on 24% of pages — saying it drops off “pretty quickly after that”, with Twitter on just 12%.

Literally any site you visit you’re likely to have Facebook, Google watching you there.

“I think people are aware now that hidden trackers are around, and slurping up their personal information. What they don’t realize, though, is how pervasive Google and Facebook trackers are,” he suggests.

“Literally any site you visit you’re likely to have Facebook, Google watching you there. That’s the piece that I think people are starting to wake up to now.”

The other problem that he argues is exacerbated by mass surveillance ad-targeting online business models is filter bubbles — aka the strategy of platforms using people’s own biases as a tactic to keep them clicking by reductively feeding them more of the same stuff.

And, again, concern about the societal impact of filter bubbles has increasingly become a mainstream discussion point in recent months and years.

Weinberg explains that the tracker blocker aspect of DDG’s new products group trackers into networks to try to make it easier for people to understand which companies are responsible for tracking you. So instead of just saying something generic — like it’s ‘blocking 25 trackers’, as a typical anti-tracker tool might — users of DDG’s tool will be told which tracker networks are being blocked and “what their purpose is”.

“When people realize the harms… of filter bubble and pervasive ads those emotionally resonant with people and they’d like to get rid of them. And this is the easiest way to do that,” he adds.

In the European Union, an updated online privacy framework, GDPR, will apply from May. This regulation makes explicit mention of online profiling, including a right for people to object to this kind of activity — and some privacy experts suggest it could cause big upheavals for adtech and online profiling.

But asked for his take on GDPR’s implications for profiling, Weinberg isn’t confident it will be much of a barrier to the web’s two main commercial surveillance entities: Facebook and Google.

“I’m a big fan of the regulation and I’m hopeful that a lot of these kind of more hidden data brokers that don’t have consumer relationships are really going to get caught out with it because they can’t get consent,” he says. “But unfortunately, the way I see it is — Facebook and Google — I don’t think they seem like they’re going to be as affected by the regulation.

“Because while consent will be required in much more vigorous ways, I think that they’re going to push that through their products. And then people will end up consenting.”

“I think you need a different consumer backlash as well — either people literally leaving the services. Or, in this case, in between: Blocking all their hidden trackers across the web. And not waiting for them to take any major action to curb their surveillance,” he adds.

Comment