Christopher Wan

The future of grocery stores will be a win-win for both stores and customers.

On one hand, stores want to decrease their operational expenditures that come from hiring cashiers and conducting inventory management. On the other hand, consumers want to decrease the friction of buying groceries. This friction includes both finding high-quality groceries at consumers’ personal price points and waiting in long lines for checkout. The future of grocery stores promises to alleviate, and even eliminate, these points of friction.

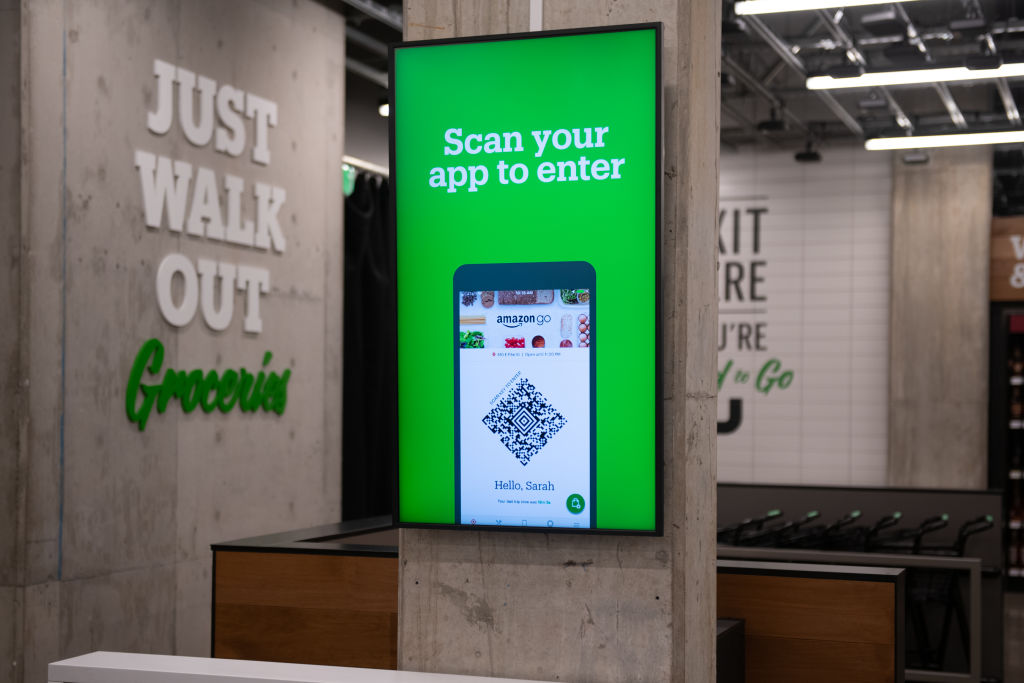

Amazon’s foray into grocery store technology provides a succinct introduction into the state of the industry. Amazon’s first act was its Amazon Go store, which opened in Seattle in early 2018. When customers enter an Amazon Go store, they swipe the Amazon app at the entrance, enabling Amazon to link purchases to their accounts. As they shop, a collection of ceiling cameras and shelf sensors identify the items and places them in a a virtual shopping cart. When they’re done shopping, Amazon automatically charges for the items they grabbed.

Earlier this year, Amazon opened a 10,400-square-foot Go store, about five times bigger than the largest prior location. At larger store sizes, however, tracking people and products gets more computationally complex and larger SKU counts become more difficult to manage. This is especially true if the computer vision AI-based system also must be retrofitted into buildings that come with nooks and crannies that can obstruct camera angles and affect lighting.

Perhaps Amazon’s confidence in its ability to scale its Go stores comes from vertical integration that enables it to optimize customer experiences through control over store format, product selection and placement.

While Amazon Go is vertically integrated, in Amazon’s second act, it revealed a separate, more horizontal strategy: Earlier this year, Amazon announced that it would license its cashierless Just Walk Out technology.

In Just Walk Out-enabled stores, shoppers enter the store using a credit card. They don’t need to download an app or create an Amazon account. Using cameras and sensors, the Just Walk Out technology detects which products shoppers take from or return to the shelves and keeps track of them. When done shopping, as in an Amazon Go store, customers can “just walk out” and their credit card will be charged for the items in their virtual cart.

Just Walk Out may enable Amazon to penetrate the market much more quickly, as Amazon promises that existing stores can be retrofitted in “as little as a few weeks.” Amazon can also get massive amounts of data to improve its computer vision systems and machine learning algorithms, accelerating the speed with which it can leverage those capabilities elsewhere.

In Amazon’s third and latest act, Amazon in July announced its Dash Cart, a departure from its two prior strategies. Rather than equipping stores with ceiling cameras and shelf sensors, Amazon is building smart carts that use a combination of computer vision and sensor fusion to identify items placed in the cart. Customers take barcoded items off shelves, place them in the cart, wait for a beep, and then one of two things happens: Either the shopper gets an alert telling him to try again, or the shopper receives a green signal to confirm the item was added to the cart correctly.

For items that don’t have a barcode, the shopper can add them to the cart by manually adding them on the cart screen and confirming the measured weight of the product. When a customer exits through the store’s Amazon Dash Cart lane, sensors automatically identify the cart, and payment is processed using the credit card on the customer’s Amazon account. The Dash Cart is specifically designed for small- to medium-sized grocery trips that fit two grocery bags and is currently only available in an Amazon Fresh store in California.

The pessimistic interpretation of Amazon’s foray into grocery technology is that its three strategies are mutually incompatible, reflecting a lack of conviction on the correct strategy to commit to. Indeed, the vertically integrated smart store strategy suggests Amazon is willing to incur massive fixed costs to optimize the customer experience. The modular smart store strategy suggests Amazon is willing to make the tradeoff in customer experience for faster market penetration.

The smart cart strategy suggests that smart stores are too complex to capture all customer behaviors correctly, thus requiring Amazon to restrict the freedom of user behavior. The more charitable interpretation, however, is that, well, Amazon is one of the most customer-centric companies in the world, and it has the capital to experiment with different approaches to figure out what works best.

While Amazon serves as a helpful case study to the current state of the industry, many other players exist in the space, all using different approaches to build an aspect of the grocery store of the future.

Cashierless checkout

According to some estimates, people spend more than 60 hours per year standing in checkout lines. Cashierless checkout changes everything, as shoppers are immediately identified upon entry and can grab products from the shelf and leave the store without having to interact with a cashier. Different companies have taken different approaches to cashierless checkout:

Smart shelves: Like Amazon Go, some companies utilize computer vision mounted on ceilings and advanced sensors on shelves to detect when shoppers take an item from the shelf. Companies associate the correct item with the correct shopper, and the shopper is charged for all the items they grabbed when they are finished with their shopping journey. Standard Cognition, Zippin and Trigo are some of the leaders in computer vision and smart shelf technology.

Smart carts and baskets: Like Amazon’s Dash Cart, some companies are moving the AI and the sensors from the ceilings and shelves to the cart. When a shopper places an item in their cart, the cart can detect exactly which item was placed and the quantity of that item. Caper Labs, for instance, is pursuing a smart cart approach. Its cart has a credit card reader for the customer to checkout without a cashier.

Touchless checkout kiosks: Touchless checkout kiosk stations use overhead cameras that verify and charge a customer for their purchase. For instance, Mashgin built a kiosk that uses computer vision to quickly verify a customer’s items when they’re done shopping. Customers can then pay using a credit card without ever having to scan a barcode.

Self-scanning: Some companies still require customers to scan items themselves, but once items are scanned, checkout becomes quick and painless. Supersmart, for instance, built a mobile app for customers to quickly scan products as they add them to their carts. When customers are finished shopping, they scan a QR code at a Supersmart kiosk, which verifies that the items in the cart match the items scanned using the mobile app. Amazon’s Dash Cart, described above, also requires a level of human involvement in manually adding certain items to the cart.

Notably, even with the approaches detailed above, cashiers may not be going anywhere just yet because they still play important roles in the customer shopping experience. Cashiers, for instance, help to bag a customer’s items quickly and efficiently. Cashiers can also conduct random checks of customer’s bags as they leave the store and check IDs for alcohol purchases. Finally, cashiers also can untangle tricky corner cases where automated systems fail to detect or validate certain shoppers’ carts. Grabango and FutureProof are therefore building hybrid cashierless checkout systems that keep a human in the loop.

Advanced software analytics

The world of atoms has lagged behind the world of bits in understanding user behavior. In the online world, cookies and sophisticated data analytics and management tools have enabled companies to track consumers’ digital footprint and behavior. However, most traditional brick-and-mortar stores lack the rich storyline of customer journeys throughout the store and only have a snapshot of the ending: What shows up on the customer’s receipt.

For instance, stores have no idea whether a customer picked an item and put it back down or how much time a customer spent looking at an item, etc. Therefore, it is worth noting that many of the cashierless checkout companies described above also bundle their hardware with software analytics for the store. This analytics will help stores and customers in a couple of ways:

Inventory management: Understanding user behavior is crucial for inventory management. The future of groceries will enable stores to examine customer behavior during a visit and potentially across different visits. As a result, stores will be able to optimize their product availability. For example, Focal Systems is building the “operating system” for inventory management. Using inexpensive cameras deployed on store shelves, Focal Systems collects data about store utilization and employee performance to reduce stores’ operational costs.

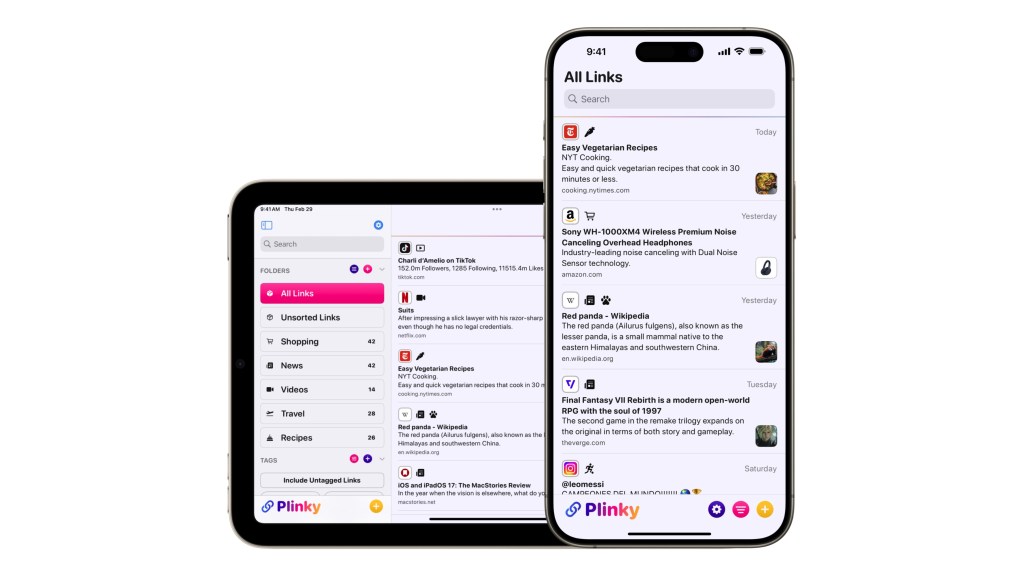

Custom promotions: Stores may even offer tailored advertisements to customers as they shop in the store. SIRL, for instance, is building a mobile app and SDK for indoor GPS and traffic analytics, enabling much richer data collection and insights into customer behavior. First, SIRL onboards stores by integrating with existing store planograms and providing a simple companion app to update those planograms in real time. Once a store is onboarded, customers can enter the store, open a mobile app that helps them navigate the store, scan products for more information and take advantage of real-time marketing discounts. Advertisers can use SIRL’s customer information like product dwell time and shopping cart items to show customers more timely relevant ads.

Robots

Many stores will also use robots that work alongside humans, either helping to fulfill customer orders in the backroom or interacting with customers and employees on the store floor.

Microfulfillment centers (MFCs): MFCs are small robotic systems that rapidly fulfill customer orders. MFCs require a small footprint relative to traditional fulfillment centers, and as a result, MFCs can be located in urban areas or in underutilized space within an existing store.

While MFCs do occupy a separate position in the e-commerce value chain because they help solve the last-mile delivery problem, MFCs also play a role in the future of grocery stores. Imagine a future where you can go to a store, place an order for certain uniform products (e.g., Coke), and go about shopping for nonuniform products (e.g., fruits, vegetables).

The MFC in the back of the store can assemble all the uniform products, and when you’re done shopping, you have all of your products ready to go. Fabric, Takeoff, and Alert Innovation are some of the leaders building and installing MFCs.

Store monitoring: Some companies are using robots that glide up and down grocery aisles to monitor product price and availability. Simbe Robotics, for instance, built Tally, a robot that uses a combination of sensors, computer vision and data tracking algorithms to manage a store’s inventory. Tally notifies store employees when it notices incorrect prices on a product or when a shelf needs restocking.

Similarly, Ahold Delhaize, which owns Food Lion, Giant and Stop & Shop in the United States, ordered 500 robots from Badger Technologies. At the beginning of 2020, Walmart also partnered with Bossa Nova Robotics to use the latter’s robots in its stores. However, Walmart recently decided to discontinue this partnership, citing concerns about how shoppers react to seeing a robot working in a store and finding not enough of an improvement in revenue or metrics to justify the expense.

Why now?

The current grocery store paradigm has ossified over the last 100 years, so why is the door to the future of grocery stores opening up now? The answer lies in the immense technological development we’ve seen converging to enable the transformation of grocery stores today. Many of the companies innovating in the space use at least one of the following technologies:

Artificial intelligence (AI) and robotics: Increasing sophistication in artificial intelligence algorithms is perhaps the largest facilitator of the future of grocery stores. Nearly all of the companies in the space are using computer vision to track which items customers are taking from shelves. Computer vision in facial recognition technology is also important as a biometric identification tool to understand who is entering the store and making purchases. Finally, AI in robotics is also crucial in the development of MFCs that autonomously pick, separate and fulfill customer orders.

Sensors: The last couple of decades, we have witnessed a proliferation of different sensors, many of which are being deployed in conjunction with computer vision in the store of the future. Indeed, computer vision alone may not be enough to detect ambiguities in product placements since cameras are, for the most part, only placed on the ceilings of stores. For instance, small items like individual pieces of candy on a bottom shelf may be partially or fully occluded.

As a result, companies like Zippin and Caper Labs are equipping their shelves and carts with weight, pressure, infrared and acoustic sensors to detect what items are being added and removed. This sensor fusion, the ability to aggregate inputs from multiple sensors, has helped companies improve their accuracy in detecting changes to shelves and carts.

Computing power and connectivity: AI algorithms need vast amounts of computing power to train and deploy accurate models. Furthermore, with cashierless checkout and robots, these algorithms are sometimes deployed at the “edge,” meaning that the cameras, robots and sensors in the stores themselves run the algorithms to draw inferences and make decisions as customers are shopping. Today’s advanced graphics processing units (GPUs) and custom application-specific integrated circuits (ASICs) enable this “edge computing.”

When edge computing is unavailable, processing can be done in the cloud, thanks to large advances in data connectivity and cloud computing, but sending the information to the cloud adds latency that wouldn’t work as seamlessly in these real-time decision-making situations.

Radio-frequency Identification (RFID): RFID uses electromagnetic fields to automatically identify and track tags attached to objects. It also obviates the need for manual barcode scanning at checkouts. RFID has traditionally been used in the high-end retail industry to detect theft, but some companies have implemented cashierless checkout by attaching RFID tags to all of a grocery store’s products.

Indeed, established industry players like Avery Dennison and Panasonic are selling RFID technology to grocery stores. DeepMagic, a startup acquired by Standard Cognition last year, built cashierless checkout kiosks using a combination of computer vision and RFID. The downside to RFID is that the time and expense of attaching RFID to each product remains high. The average price of RFID in the early 2000s was approximately $.50/tag, and while the price has plummeted to about $.08/tag today, that remains a relatively high operational cost for cheaper grocery items.

Challenges

While the technological trends are pointing to an inevitable transformation of the grocery store, this transformation is by no means sure to happen immediately. Indeed, the following barriers may prolong the dominance of the current grocery store paradigm and delay the timeline for change.

Edge cases: The problem, as with many other emerging technologies utilizing artificial intelligence, is that AI can achieve 95% or 99% accuracy, but to ensure a truly delightful end-to-end customer experience, an AI system needs to achieve 99.99999% accuracy. In the case of grocery shopping, the typical case is easy to cover. An individual shopper puts items into their cart and checks out. However, what if they pick up an item, walk around, decide they don’t need it anymore, and leaves it on a different shelf? What if they are shopping with their friends, some of whom pick items up on their behalf? The devil’s in the details and edge cases matter.

Companies need to solve these edge cases in a way that is organic to user behavior. In the interim, many stores have included a human in the loop to review these edge cases when the user leaves the store. Some stores also fix the customer’s receipt shortly after the customer leaves if the store detected an anomaly.

Some companies like Amazon (discussed above) have tried to simplify the problem by resorting to smart carts instead of smart shelves. While smart shelves inevitably become entangled with many of the edge cases described above, smart carts offer a simpler value proposition: Automatically charge the shopper at the end of their shopping journey for whatever is in their cart, regardless of who is with them and what they did with other products.

High capital expenditures: The corollary to the point above is that as you train and deploy your AI to solve more edge cases, you need more compute power and powerful hardware, therefore increasing your capital expenditures. The number of GPUs for each camera or robot will vary depending on the amount of data the system produces and the algorithmic complexity of the model. This, in turn, can vary based on the type of algorithms, the type of GPUs, the resolution of the input to the model, the downsampling of the images, the resolution of the cameras and the frames per second of the cameras.

A startup trying to outfit a grocery store with AI may then be stuck in a cap-ex Catch-22: If it pursues an edge computing approach, then stores would need to be outfitted with immense data storage and processing capabilities. On the other hand, if it pursues a cloud computing approach, then it would either incur significant capital expenditure to build out its servers or incur significant operating expenditure to use an existing cloud provider like AWS or Azure. Meanwhile, thanks to Moore’s law, the cost and performance of compute will continue to decrease, so perhaps the timing for the future of grocery stores may still be, well, in the future.

Customization and scalability: In today’s competitive landscape, companies are taking a modular approach, where the development of the technology is modularized from the ownership of the store itself. In other words, stores like Trader Joe’s purchase the hardware and software from other companies rather than developing it themselves. The problem, though, is that onboarding a new store incurs significant costs. For instance, stores come in different shapes and sizes but need to be outfitted with cameras on the ceilings and sensors on their shelves.

Stores need to share their entire inventory of items for the startup to catalog and train their algorithms on. Stores need to share entire planograms of their store layouts. Stores may even need to renegotiate contracts with their local internet service providers, given the amount of communication between the edge and the cloud. All of these costs may make the status quo more attractive.

To reduce this complexity, some companies are taking a more integrated approach by owning not only the software and hardware but also aspects of the physical store itself. Amazon Go, for instance, began with this fully integrated approach although it recently began licensing its software to other stores. AiFi offers Nanostore, a mini, physical store that AiFi can rapidly build, deploy and integrate with its own cashierless checkout. Other stores can then purchase a Nanostore and fill it with its own products.

Privacy and regulation: Futuristic grocery stores will identify and track shoppers as they go about their shopping journeys, raising privacy concerns. Companies offering cashierless checkout and advanced software analytics will therefore need to comply with regulations such as the European General Data Privacy Regulation (GDPR) and the California Consumer Privacy Act. Many states and municipalities within the United States have also begun rolling out regulations on facial recognition technology, which could complicate the biometric identification task.

Portland, for instance, recently passed the most stringent ban on facial recognition in the country. This regulation bans the use of facial recognition not only by the government, but also by private entities in public spaces. Increasing and varying regulation in this space among various jurisdictions may fragment the speed of innovation.

Market uncertainty with e-commerce creep: I’d be remiss if I didn’t at least raise the possibility that e-commerce could completely dominate traditional commerce in the coming years and subsequently obviate the need for most grocery stores. With the rise of apps like Amazon Prime Now, Instacart and Shipt, combined with COVID-19 pandemic, online grocery sales have grown 40% during 2020 to a 3.5% share of total groceries expenditure.

While that figure is low today, if we assume a continued 40% compound annual growth rate, e-groceries would become 100% of total groceries expenditure within the next 10 years. Even if e-commerce does come to dominate, though, some players may be safer than others. For instance, microfulfillment centers will play an important role in e-commerce because it helps solve the last-mile delivery problem, and custom promotions can be used to market new products to customers whether a store exists.

Comparing different elements of the grocery store of the future

| Edge case complexity | CapEx | Scalability challenges | Regulation | Threat from e-commerce predation | TRL* | |

| Cashierless checkout | ||||||

| Smart shelves | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ |

| Smart carts | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↑↑ |

| Touchless kiosk | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑↑ |

| Advanced software | ||||||

| Inventory management | ↓ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↑ | ↓ | ↑↑ |

| Custom promotions | ↓↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↑ | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↑↑↑ |

| Robots | ||||||

| Micro-fulfillment centers | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↑↑↑ | ↓ | ↓↓↓ | ↑↑ |

| Store monitoring | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↑↑ | ↓↓ | ↓ | ↑↑ |

*TRL: technology readiness level

While tomorrow’s grocery stores will certainly be an awesome paradigm shift from the status quo, we at Bessemer also have our eyes peeled for the day after tomorrow. What tectonic shifts will occur in the next couple of decades, or longer? Perhaps virtual reality will become sophisticated enough that we can shop for real items in virtual grocery stores. Perhaps we’ll see the rise of mobile ministores that travel to us, rather than requiring us to travel to them.

Or, perhaps gene-editing and lab-grown meat will become so cheap and widespread that customers can reorder previous purchases with exact precision, down to the molecular level. Whatever the case may be, the future of groceries is an exciting industry, and certainly one that we are excited to dig into. Tell us what you think at grocery@bvp.com.

Amazon is now selling its cashierless store technology to other retailers

Comment