Update (October 21st 11:30 am PT)

With the help of NASA, ESA has located their failed Schiaparelli lander.

NASA’s Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter, a Mars-orbiting satellite equipped with cameras, was able to image the Schiaparelli landing site. In the before and after images above you can see a large dark dot above a smaller white dot.

Preliminary analysis suggests that the smaller white dot on the bottom is the parachute and back shield that were jettisoned away from the lander. The larger feature is likely to be the bigger-than-expected impact site of the lander. Schiaparelli probably free fell for too long and, when it landed, it kicked up dust and debris, creating the impact feature we see in the image.

. @NASA Mars Reconnaissance Orbiter has imaged changes on #Mars surface linked

to #ExoMars @ESA_EDM https://t.co/QN4BqV7xIR pic.twitter.com/BD7XKhB1oO— European Space Agency (@esa) October 21, 2016

Next week, MRO’s high-resolution camera, HiRISE, will be used to image the location and hopefully reveal more about the scene of the landing.

Original (October 20th)

Yesterday morning, the European Space Agency hoped to become the second entity in history to operate a robot on Mars. Unfortunately, things didn’t go as planned. ESA’s Schiaparelli rover is on the surface of Mars, but all signs point to a hard landing and a broken robot.

The good news, however, is that Schiaparelli was only one part of ESA’s ExoMars mission. Schiaparelli, which has been described as an experimental lander, was joined by an orbiter known as the Trace Gas Orbiter. TGO was successfully inserted into Martian orbit and is working properly.

With TGO, ESA now has two operational satellites around Mars, providing scientific data to scientists here on Earth.

Even though the Schiaparelli lander seems to have been a failure, ESA was able to collect engineering data from the spacecraft during its descent. This information will enable the ExoMars engineering team to understand what went wrong, and what they’ll need to do differently in the future.

What Went Wrong?

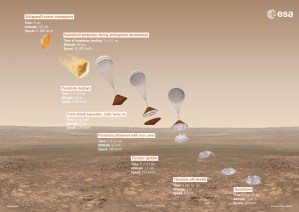

ESA needs more time to make sense of the wealth of data they’ve collected, but early analysis suggests a problem occurred in Schiaparelli’s final moments of descent, specifically when it was scheduled to jettison its parachute and heatshield, and when firing its thrusters before touchdown.

Here’s what was supposed to happen:

Over the course of six minutes, the lander had to decelerate from traveling 21,000 km/hour at an altitude of 122.5 km to traveling around 7 km/hour at just 2 km above the surface.

Schiaparelli actually achieved most of this deceleration (from 21,000 km/hour to 1,700 km/hour) simply by moving through the Martian atmosphere. The lander was protected during this violent phase by an aerodynamic heatshield.

This first phase went as planned.

After that, Schiaparelli had to deploy a large parachute to further slow its descent.

This stage also went accordingly.

Once the lander moved down to 7 km above the surface, its front heatshield was supposed to separate from the lander and a radar altimeter on board was designed to tell Schiaparelli how fast it was moving and how far away from the surface it was.

Then the time came when Schiaparelli was supposed to jettison its parachute and the remainder of its heatshield. It’s at this point when things went awry.

“Following this phase, the lander definitely did not behave as expected.” Andrea Accomazzo, Head of the Solar and Planetary Missions Division at ESA

In a press release, ESA stated that the ejection seems to have happened earlier than expected.

In a nominal descent, after the parachute and heat shield were jettisoned away from the lander, Schiaparelli would have fired its thrusters to slow itself to around 4 km/hour. At this point, the lander was supposed to turn the engines off and free fall the rest of the way to the ground. It’s crushable structure on the bottom of the spacecraft was designed to cushion the fall.

Data suggests that Schiaparelli’s thrusters did, in fact, fire, but that they switched off sooner than expected. Right now, they’re not sure how far away from the surface Schiaparelli was when this all happened.

What we know for sure is that ESA landed a robot on the surface of Mars, but things didn’t go as planned, and that robot isn’t working at this moment in time.

History Repeating itself?

Unfortunately, this scenario is all too familiar for ESA.

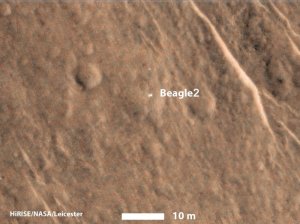

Nearly thirteen years ago, ESA sent an orbiter and a lander to Mars as part of their Mars Express mission. While the Mars Express orbiter was successfully inserted into orbit, the Beagle 2 lander was declared lost after repeated attempts to communicate with the robot were unsuccessful.

Unfortunately, no concrete reason was found for why the Beagle 2 landing didn’t go as planned. For scientists and engineers, that doesn’t really help when it comes to innovating and refining their methods for the next go-around.

What’s different about Schiaparelli is that the ESA team was able to obtain more engineering information about its descent. This is incredibly important, as it will help them understand what worked and, hopefully, what went wrong. ESA can use that information to better their chances of a successful landing in the future.

Mars is Hard

Landing on Mars is incredibly difficult for a few reasons. To get to Mars, a spacecraft must travel at incredibly high speeds – ExoMars, for example, was traveling at 21,000 km/hour. Then, the spacecraft has to decelerate to 0 km/hour (landing) – without destroying itself (soft-landing).

Now, to do that, successful missions have used a combination of a few different technologies: parachutes, retro-thrusters, sky cranes, and air bags.

To understand why you need a combination of descent technologies you need to know that Mars has a thin atmosphere. While it’s about 100 times thinner than Earth’s, the Martian atmosphere is still thick enough to rough-up your spacecraft as it zips through at thousands of km/hour (requiring a heavy heatshield that will later need to be jettisoned).

And although parachutes are very effective in slowing down and stabilizing a Mars rover, the atmosphere is too thin to rely on them alone.

This means that, in addition to a heatshield and parachute, a lander will need something else to bring it safely to the ground. Additional components add complexity and additional ways the mission can fail. Not to mention the fact that all of these things have to happen at precise moments, in a precise order, extremely quickly, and autonomously.

If all you needed was a heat shield and a parachute, ESA may have an operational robot on Mars today. But that’s not the case, because Mars is hard. In fact, only seven spacecraft in history have successfully touched down on the red planet – all of them from NASA.

Despite Everything, Science Awaits

The failure of Schiaparelli, shouldn’t overshadow the success of TGO. After traveling for seven months and 300 million miles, TGO was successfully inserted into orbit around Mars. ESA now has two operational satellites (Mars Express is the second) orbiting a planet that’s millions of kilometers away, and that is an incredible feat.

Update from Deputy Flight Director Micha Schmidt: @ESA_TGO is in excellent shape this morning! #ExoMars

— ESA Operations (@esaoperations) October 20, 2016

TGO’s orbit will bring it to within 400 kilometers of the Martian surface in order to collect scientific data from the atmosphere. For reference, the International Space Station orbits the Earth at an altitude of 400 kilometers.

I’ve detailed the science goals of TGO in a previous TechCrunch article.

The instruments on board the orbiter will be used to detect and characterize trace gases in the Martian atmosphere with an improved accuracy of 3 orders of magnitude compared to previous measurements.

Scientists are particularly interested in characterizing the presence of small amounts of methane that have been detected in the Martian atmosphere. This piques researchers’ interests because living organisms produce large amounts of methane here on Earth. While there are also purely geological processes that produce the gas, it’s a good starting point for those searching for life on Mars.

To make matters more interesting, methane is short-lived on geological time scales. Its presence suggests that there’s an active source producing the gas on Mars today. Further research is required to determine where the methane is coming from.

The Trace Gas Orbiter will also be used to map hydrogen levels just beneath the Martian surface. Locations where hydrogen is found may indicate water-ice deposits, which could be useful for future crewed missions. Landing locations for crewed missions may be influenced by these findings since water-ice can be leveraged to generate potable water or rocket fuel.

TGO and Schiaparelli made up Phase 1 of the ExoMars mission. ExoMars-Phase 2 is scheduled to launch in 2020 and will deliver a European rover and a Russian surface platform to the Martian surface. It will be interesting to see how, if at all, information from the Schiaparelli failure will affect the landing strategy for ExoMars Phase 2.

Comment