After some katzenjammer about just how many comments were submitted to the Federal Communications Commission (FCC) regarding its notice of proposed rulemaking (NPRM) dealing with net neutrality, the governmental agency confirmed today that nearly 4 million comments were in fact submitted.

Some had alleged that either several hundred thousand comments were missing, or perhaps that the agency had overstated the number of comments that it had received. As it turns out, the comments were missing, but they were not lost.

The FCC today released a blog post that was at once exculpatory, and funny. Here’s the FCC’s explanation of how the comments in question didn’t make it out into the public:

[I]t’s important that people understand that much of the confusion stems from the fact that the Commission has an 18-year-old Electronic Comment Filing system (ECFS), which was not built to handle this unprecedented volume of comments nor initially designed to export comments via XML. This forced the Commission’s information technology team to cobble solutions together MacGyver-style. […]

In parsing the XML files in question, it appears that nearly 680,000 of the comments were not transferred successfully from ECFS to the XML files. This is due to a technical error involving Apache Solr, an open source tool the FCC used to produce the XML files. We plan to fix this problem by issuing a new set of XML files after the New Year with the full set of comments received during the reply period.

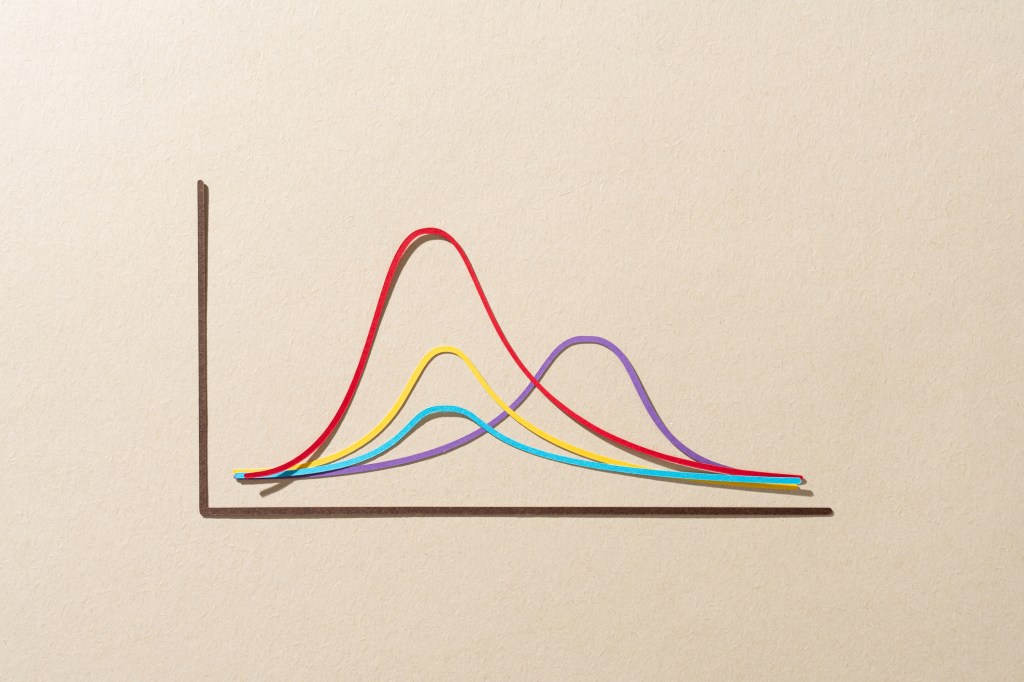

There is a scrap about what percentage of the comments that the FCC has received have been in favor of net neutrality, or opposed to it. Initial analysis had the tilt firmly in favor of passing a new open Internet regulatory structure. Later perusal of comments noted a potential slant in the other direction.

It will be interesting to see what the final tally says, when the data is public and properly parsed.

The FCC is expected to debut new net neutrality regulations in February or March. There is talk of the new Congress, with its new majority, working to either undermine the capability of the FCC to enforce net neutrality, or perhaps even pass a new legal foundation for it to use, allowing it to avoid trying to bend Title II of the Communications Act to its will.

For now, we know that net neutrality has been precisely as polarizing in the public as we previously thought. Someone get the FCC some new servers.

Comment