Steve Vassallo

More posts from Steve Vassallo

The following is an excerpt from The Way to Design, a guide to becoming a designer founder and to building design-centric businesses. Adapted and reprinted with the author’s permission.

Until very recently, success in Silicon Valley required focusing almost single-mindedly on an organization’s technical prowess. It meant having an unimpeachable technical founder, 10X engineers, a relentless devotion to computing dominance. Expending valuable time on anything else — particularly design — was evidence of distraction from the real work of the company.

But things have changed dramatically in just a few short years, and increasingly, design has become as indispensable as technology. Three things are responsible for this remarkable shift. First, whether you’re working on hardware or hosted software, the underlying technology to prototype, produce, and launch products has only become better, cheaper, and faster over the last 25 years. Free and easy-to-use CAD software, 3D printing, and crowdfunding have made it easier and faster than ever to design, sell, and ship.

Where once engineers used to rely on raw programming languages to create software; today, they build from open-source libraries and preexisting technology platforms. In the consumer internet world in particular, the marginal cost of software is zero—and design is now the differentiator.

“The expectation for a new company is so much higher now,” Airbnb’s Joe Gebbia said to me when I interviewed him, “because what they did in six months [10 years ago] someone could do now in a week.” And therefore, “People have to come with more value.”

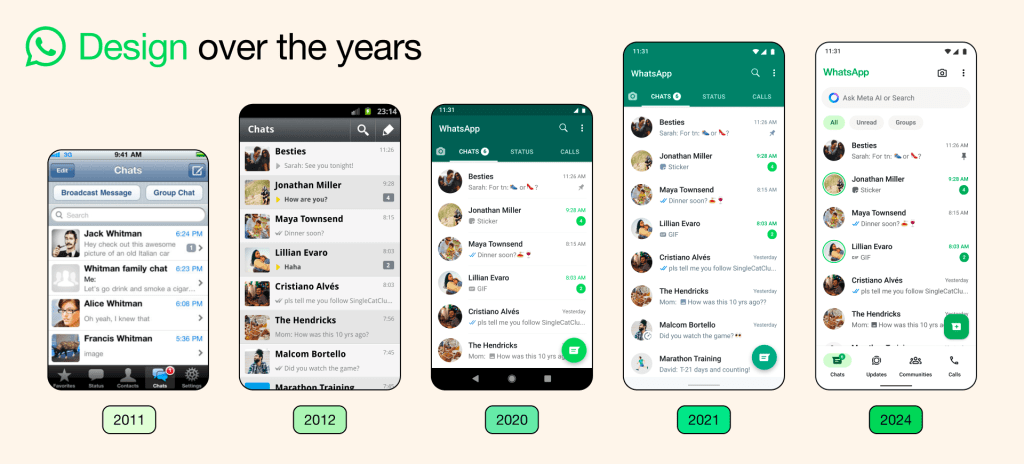

The second reason that design has moved center stage is that consumer expectations have evolved. Businesses, even in the very recent past, weren’t doomed to certain failure because of a weak emphasis on design. The bottoms of drawers across the free world are littered with poorly designed products that sold well because of brilliant sales and marketing. But the public has come to expect more.

Thanks to the work of visionaries like Bill Moggridge, David Kelley, and Steve Jobs, people want user-devoted, frictionless experiences in their interactions with technology. Jobs’ influence is especially pronounced. Perhaps no single product has reshaped what people expect of designed technology more than the iPhone. Ever since its release a decade ago, consumer demand for useful, beautiful product experiences have grown more insistent.

In contrast, you can follow the trail of Palm’s death crawl all the way back to its chief marketing officer saying, “Design is a commodity.”

Photo: Vasily Pindyurin/Getty Images

Seek And You Shall Design

The final reason that design has become essential is that its scope and meaning have changed. When most laypeople hear the term “design,” what comes to mind are things like a Dieter Rams stereo receiver, a Noguchi coffee table, one of the homes featured in Dwell, a Giugiaro concept car, maybe a well-turned brand logo.

I’m a craftsman at heart and I honor this form of design. But “design” has come to mean much more than craft. John Arnold, perhaps the originator of the design movement at Stanford, taught a course called “How to Ask a Question.” His belief was that “Each of man’s advances was started by a question….Knowing what questions to ask and how to ask them is sometimes more important than the eventual answers.”

That’s what design is at the most profound level, and what I’m talking about when I talk about design in this book. It’s not aesthetics. It’s knowing what questions to ask and how to ask them, be it about a small product or a planetary system.

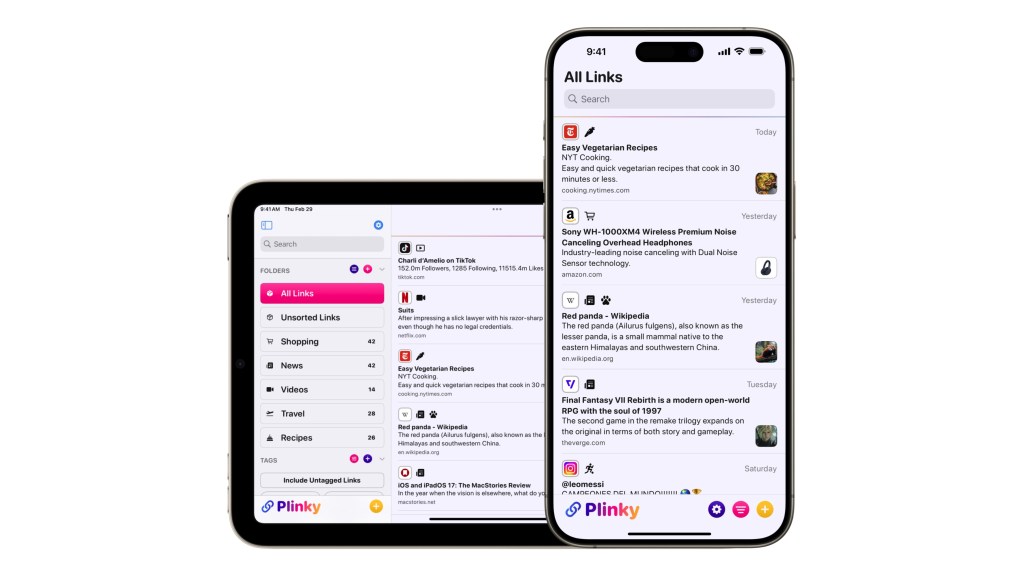

I met the designer-founder of Pocket, Nate Weiner, at a design event at Stanford and later invested in his startup. When I interviewed him for my project on designer founders, Weiner told me that at his company, Pocket, the automatic retort to any questions regarding feasibility is, “Anything is a possible.”

“Can we do this is? is the wrong question to ask. It’s Why should we do this? How should we do this?…It doesn’t matter what ideas you have, it’s all about Does this solve the problem?” Weiner says. In a world in which you can build anything, the onus for entrepreneurs has shifted from figuring out if you can build something to understanding whether it’s worth building it in the first place. And that’s why design is now more than window dressing.

Photo: Yuri Arcurs/Getty Images

Design is The What

What should you be building? What’s the right opportunity to go after? What’s the right problem to solve? Asking the right question is half the answer. Design is not about the drapes or the drop shadows. Design is a messy, holistic, human-centric process for solving problems—not just stylistic problems, but problems of all manner and level of importance.

Ask Diego Rodriguez, Global Managing Director at IDEO, which airline he thinks is the best design-led and in his opinion it’s not Virgin America, despite the care that that airline puts into things like lighting and pilot’s jackets. “Cool, but that’s all veneer,” he says. Instead, Diego thinks the real design genius in the industry is Southwest Airlines’ co-founder and former CEO Herb Kelleher, who “completely rethought the paradigm of how you get on an airplane.”

Kelleher solved an efficiency problem and, in doing so, turned Southwest into one of the safest and only consistently profitable airline in the country. These kinds of solutions aren’t necessarily pretty, but they’re innovative and effective.

This notion of design lines up with the most recent scholarship on creativity, which Scott Klemmer, cofounder and director of the Design Lab at UC San Diego, summed up as, “You need to know the things that you need to know to solve the problem. And you need to not believe things that will get in the way of solving the problem.”

Viewed from this perspective, design is about searching out a product’s or an organization’s purpose—the problem it solves—and then painstakingly making sure every facet of the solution supports this purpose.

Design is a way of thinking.

Was Lost But Now I’m A Founder

Where do we go from here? It’s my conviction that the 21st century will be the designer’s century, because I believe that design is the greatest lever for building the greatest companies to come. The most interesting innovation is happening at the top of the stack—at the interface with end users— where technology development intersects with design and where a swipe right or a hold might decide the next breakout business.

Unfortunately, despite how indispensable design is today, a stark gap persists: Not many people running top companies come from design backgrounds. According to the most recent data I could find, only 15 percent of the members of FounderDating claim design as their primary skillset. And, as its former CEO said, once you correct “for people who are more design-appreciators than designers, it’s probably closer to 6 percent.”

Yes, there are notable exceptions. But there should be more. And there will be—if designers start seeing themselves more often as entrepreneurs. As the builders not just of products, but of companies. Leaders not just of design but of people. Designers must embrace the entrepreneurial spirit.

When I left Stanford and began my career in product development at IDEO, I was set up with a $15,000 workstation and a $20,000 CAD package sold by expensive sales reps and accompanied by a one-week training course in Boston. My prototypes cost $50,000 and were made in machine shops on equipment that ran upwards of half a million dollars. When we were ready to release for mass manufacture, we sent drawings and, in some cases, 3D files to toolmakers who spent 12 weeks hogging out hardened steel tools that cost no less than $100,000 per part.

Slowly, my product would wind its way through the labyrinth of distribution, ultimately landing in retail stores which required their own care and feeding — point of purchase displays, end caps, promotional materials, in some cases, training. And for all of this hard work, you might earn 40 points of gross margin, less than the end retailer that served as a shelf and not much more.

Today, 20 years later, you can design a product with the freeware version of SketchUp, make your first rapid prototype on your own desktop MakerBot, raise $100,000 in crowd-funding on Kickstarter, purchase $5,000 soft tools from PCH, set up virtual distribution with Shipwire or Amazon or both, and market and sell directly to your customers off your own website.

The tools really are in your hands now. But the cardinal question that every aspiring designer founder needs to answer before embarking on their entrepreneurial odyssey has changed. It is no longer: Can you build the product? The starting point is now: Why are you building it at all?

Comment