I have been on a bit of an EdTech binge writing spree the past few weeks. Part of the reason is that I feel the vast majority of educators and entrepreneurs are finally realizing that Silicon Valley didn’t get it right the first time with our approach to technology and the classroom.

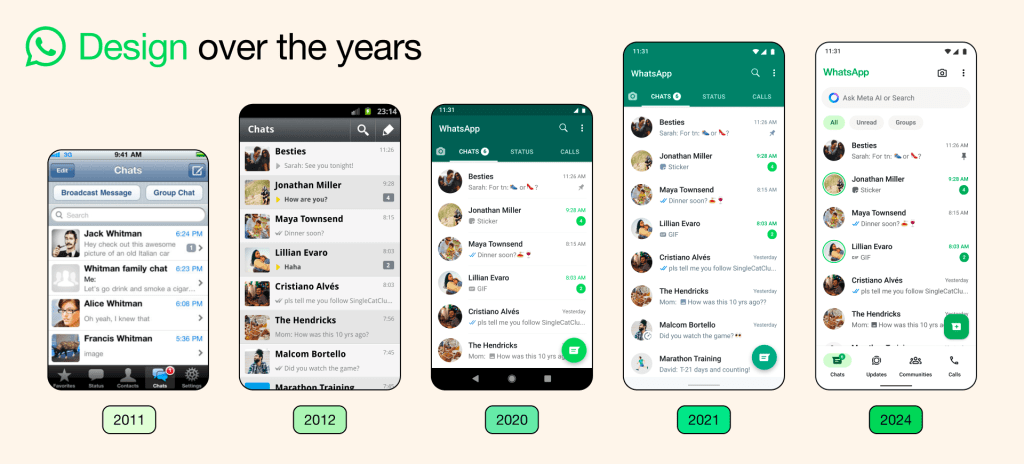

Certainly, some content is more freely available than before, an absolutely wonderful improvement for access and equality. However, the day-to-day work of education hasn’t changed all that much, despite the hype emanating from startups. While Silicon Valley has argued that it would revolutionize education, the reality is that at its best, it has augmented the classic model and not replaced it.

The other reason for my interest is more personal: I am currently teaching my first class of students. In this case, three dozen Korean college students from a top-ranked local university who are taking a class on startups and entrepreneurship.

It’s amazing to me how unprepared I was for the actual pedagogical challenges of educating my students. I had asked one professor about teaching before leaving on this trip, and the response I received was “You’ve been a student all your life, so teaching should be easy.” When it comes to advice, you really do get what you pay for.

Unfortunately, that sort of thinking is endemic not just to elite professors at Ivy League schools, but also the technologists who think they are going to revolutionize the classroom. Teaching is perceived to be the easy part of education, as if there is something else that has greater import. We know that students with better teachers perform significantly better than peers with worse teachers, so clearly, teaching matters.

My own experience this past week is telling. My challenges started almost immediately when I agreed to teach this class on startups. What should I teach? How should my course be structured? I have five hours of class per day to schedule for two weeks, and I can’t just lob content at students and expect them to understand what is going on, particularly in the summer when expectations for studying are (acceptably) lower.

So I did what any person in the 21st century did, and I searched Google. It was here that it hit me just how basic our pedagogical thinking really is.

What works in the classroom? How should different students be educated differently? As I searched Google, there were, of course, plenty of examples of entrepreneurship and startup courses, but little information about which ones were actually successful.

Other questions popped up. How do I develop the right kinds of in-class activities and assignments to reach the learning outcomes I am looking for? Should I use the same course structure for a summer accelerated course as with a course designed for a full semester?

I was hoping for a more data-centric approach, some sort of A/B testing of curricula so that I could understand which courses or pedagogical approaches were most successful. Given the success of online education, random experiments with content would seem to be easy to accomplish. Yet, such work has barely started.

Given the inordinate amount of attention that is paid to consumer products as well as data science in Silicon Valley, I would have expected far more action here. I am sure the MOOCs have some insights from their courses, which is great. However, those insights are rarely shared with me, the teacher looking to build the right kind of educational experience for my students.

The problem with EdTech then is not necessarily our approach, but rather our focus. While data is critical to education, we’ve been stressing the wrong kind of consumers for too long. We have always taken students to be the “ultimate” consumer in education – they are the ones who are receiving the education, and often paying for it as well.

However, there is another side in this market, and that is the educators. Despite all the technology gains made by students, educators have received just a handful of useful tools to help with better management of their classrooms and the learning process. There have been far fewer “revolutionary” attempts to transform teachers than to just entirely replace the education experience.

I don’t think we are ever going to take humans out of education. Education is fundamentally a social process, and even if we replace some elements of this process with computers, there will always be room for humans to help their students in an effective manner.

Startups should think through how they can rebuild the experience of teaching a class. How can I be alerted to important questions to cover, even when my students aren’t asking questions? How can I learn which material might be most effective, even before I teach it?

These are data science problems, and all of this is learned natively by master teachers over the course of their careers. What I want to see is a startup that can completely transform the development of teachers. If we can take a teacher and make them almost equally effective in just one half or even one tenth the time, we may have done more for human development than any startup has.

There is no question that building a library of insights and eventually developing a computerized intuition about education are massive ideas. It may even require us to fully work out how the brain works, perhaps the single most important (and difficult!) research project of the 21st century. But this is not an impossible problem, and it seems the right kind of “reach” challenge to solve for the next generation of education startups.

This is an exciting moment for education technology startups to reconsider their future. We hardly should forget about students – but they need to be perceived as equals in this whole enterprise. Only when we build tools that revolutionize the experiences of both sides of this market will we see the kind of education progress we have hoped for with technology.

Comment