Over one billion cell phones have been sold worldwide in the last year, but in the US or Europe, the mobile Internet is still catching on relatively slowly. There even was a heated debate in the blogosphere just recently whether the mobile web has a future at all.

Over one billion cell phones have been sold worldwide in the last year, but in the US or Europe, the mobile Internet is still catching on relatively slowly. There even was a heated debate in the blogosphere just recently whether the mobile web has a future at all.

However, this has never been a question in one specific region of the world: In Japan, since 2006 more people have been accessing the web through cell phones than through PCs. Is this a picture of things to come in other countries?

Not necessarily. The interplay of five specific factors paved the way for the success of the mobile web in Japan (where I live) and largely explains why it hasn’t taken off yet elsewhere:

- the ubiquity of advanced cell phones combined with a vast selection of tailor-made services

- tech-savvy customers who often had their first web experience on a cell phone

- a reliable technical infrastructure

- symbiotic business relations between carriers and content providers

- relatively sound regulatory policy

Three catalysts for growth: superior phones, a lot of content and demanding customers

Japan’s image as a high-speed testbed for the world’s most advanced mobile technology is well-deserved. A staggering 90 million 3G handsets are currently in circulation. Over 70% of people in this nation of 127 million are subscribed to mobile web data plans. By way of comparison: The 3G penetration rate stands at 23.8% in the US (where 52 million 3G handsets are on the market) and at 11.1% in Europe. 15.6% of American mobile subscribers use the mobile web.

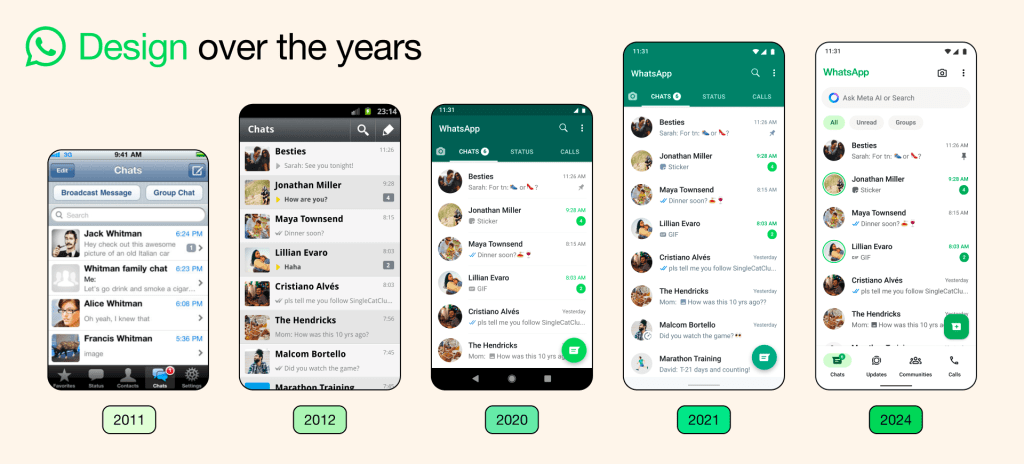

The country’s three main carriers (SoftBank, KDDI au and market leader NTT Docomo) are churning out around 100 different Internet-enabled 3G handsets per year, each equipped with a whole array of flashy functions (the iPhone made its debut in this country only last month). Japanese people use their “Keitai” for over-the-counter payments (e-wallet), as a commuter pass in public transportation, 2D barcode reader, health control terminal, dictionary, karaoke player, digital TV, music player, e-book, and much more.

Some handsets even feature video transfer from Blu-ray recorders, alarm buzzers with direct connection to the nearest police station or voice-to-text translation. In June, Docomo introduced a home service for owners of Wi-Fi-enabled cell phones to access mobile web sites at a maximum of 54 Mbps.

The availability of cutting-edge phones is one reason why many Japanese people don’t own a PC but would rather browse the web exclusively on mobile devices. And it’s not just for short bursts. They never write SMS either but rather thumb-text push-mails, often containing little icons, emoticons and coded youth slang acronyms. Booking flights online, ordering clothes, auctioning off used stuff, gaming, paying for movie tickets via direct debit: all of this has been possible on Japanese mobile phones for years now.

Semi-walled gardens in a flawless technical environment

Japanese companies never tried to duplicate the wired Internet experience but rather developed unique mobile ecosystems specifically for deployment on cell phones. Docomo’s i-mode kicked off the boom when it launched in early 1999 and was quickly followed by proprietary web systems established by competitors.

Today, the mobile web in Japan is fast, sophisticated, technically stable, and easy-to-use. Users press one dedicated button on the phone and are online within seconds, usually starting to navigate via menus predetermined in the carrier’s landing page. Alternatively users can type in URLs directly to get to mobile web sites, which can then be conveniently browsed by using one-key shortcuts.

Accessing the fixed Internet is also possible. Docomo, for example, uses a mix between a modified version of HTML and several i-mode-only protocols. This means that au’s EZweb subscribers are fenced out of Docomo’s web system (and vice versa). By the way: WAP never gained a foothold in this country.

But even in Japan’s mobile industry all is not well: Developers frequently deplore insufficient CSS, a lack of cookie and scripting support and restrictions imposed by operators and the Japanese government, i.e. especially with content regarded as harmful to children.

Powerful trio: Forward-looking politicians, carriers and content providers

Next to charging end consumers for their services, Japan’s mobile web operators generate revenue by making sites and content providers pay considerable fees for prominent positions in their default menus. Carriers also double as centralized billing institutions, significantly facilitating transactions conducted on cell phones. If a user downloads a game from an i-mode site, for example, Docomo keeps about 10% of the fee for itself. The content provider gets the rest, while the user conveniently pays the total via the monthly phone bill.

This means the business of operators and content providers alike is based on a 3-pillar kiosk model.

Carriers provide:

- stable connectivity and technical infrastructure

- system of timely and correct payment flows (for subscribers and content providers)

- willingness to share revenues

This framework motivates content providers to ensure:

- development of compelling content

- advertising of their services

- willingness to pay billing fees to carriers

This development was spurred by the Japanese government: To politically boost 3G adoption, carriers never had to pay a single Yen for mobile phone bandwidth. By way of comparison: In 2000 and 2001, the 3G licences in the UK and Germany were given out for $58 billion and $78 billion, respectively. In Japan, government policy was aimed at kick-starting a market, not to filling its own coffers. And it worked.

The country’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communications says business carried out through cell phones in Japan was worth $106 billion in 2007 (up 23% from 2006), with m-commerce accounting for $67 billion and the mobile content market for $39 billion. Just one example: Cell phone owners downloaded music worth $10.2 billion, 42% more than in 2006.

Japan quickly managed to transform into a super-mobile society and this development might be hard to replicate, at least in the same way. What will be interesting to see is whether the mobile web emerging in the U.S. and elsewhere can leapfrog Japan by embracing more open standards and doing away with walled gardens. The jury is still out on that one.

In the meantime, Japan wouldn’t be Japan if it wasn’t thinking even further ahead. Think next-generation mobile networks: In March already, Docomo successfully transmitted 250Mbps packets in an experimental Super 3G system, planning to end preparations for the eventual launch by 2009.

(Photo by Matsuyuki).

Comment