Developing Story

User data leaks at Facebook pull tech further into political debate

New revelations from The New York Times and an admission from Facebook about the improper use of user data by Cambridge Analytica have once again thrown a spotlight on the technology industry’s inadequate privacy protections.

Here is how to delete Facebook

Some of us have been on Facebook for more than a decade, but all good things come to an end. Over the past 18 months, Facebook has been in a downward spiral. The social network is in the eye of a controversy storm, with fake news, Russia’s meddling in the 2016 presidential election, and misuse of personal data by Cambridge Analytica swirling around Menlo Park.

Meanwhile, the company has lost billions in value, all coming down to the fact that the public’s trust in Facebook has been eroded, perhaps beyond repair.

If you’re ready to jump ship, the process isn’t all that difficult.

The first step is to make sure you have a copy of all your Facebook information. Facebook makes it relatively simple to download an archive of your account, which includes your Timeline info, posts you have shared, messages and photos, as well as more hidden information like ads you have clicked on, the IP addresses that are logged when you log into or out of Facebook, and more.

You can learn all about downloading your Archive here.

To go ahead and download, just go to the Settings page once you’re logged in to Facebook and click “Download a copy of your Facebook data.”

Remember, you can’t go back and download your archive once you’ve deleted your account, so if you want that info at your fingertips, make sure to download the archive first.

Before you delete your account, know this: once your account is deleted, it can’t be recovered. If ever you want to rejoin Facebook, you’ll be starting from scratch.

Oddly, finding the button to delete your Facebook account isn’t available in the settings or menu. It lives on an outside page, which you can find by clicking right here.

Important note: It takes a few days from the time you click the Delete button to the time that your account is actually terminated. If you sign on during that period, the account will no longer be marked for termination and you’ll have to start over. It will take up to 90 days for your account to be fully deleted.

Moreover, some information like log records are stored in Facebook’s database after the account is fully deleted, but the company says that information is not personally identifiable. Information like messages you’ve sent to friends will still be accessible to them.

Keep in mind, Facebook still likely has access to a good deal of your data long after you’ve deleted your account. Plus, Facebook owns WhatsApp and Instagram. So if you really want to stop feeding data into the Facebook machine, you likely need to go ahead and delete those apps as well.

Facebook has lost $60 billion in value

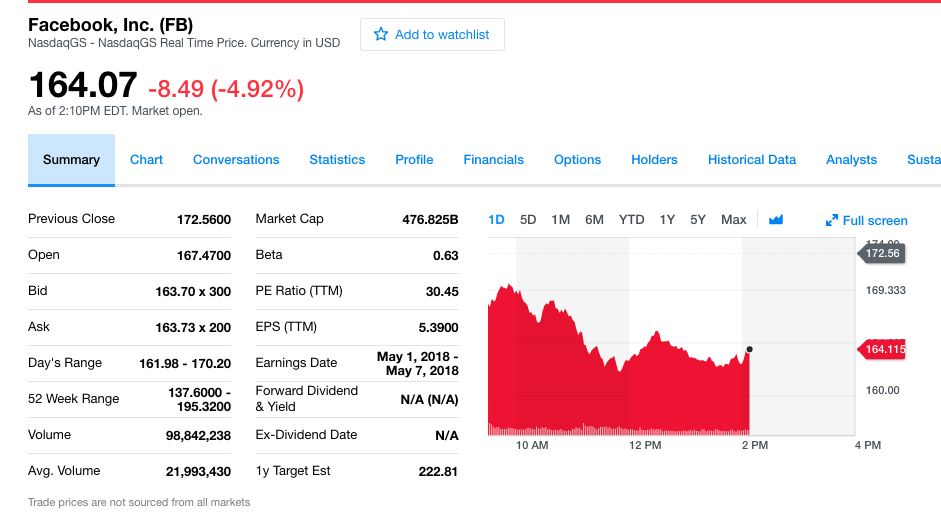

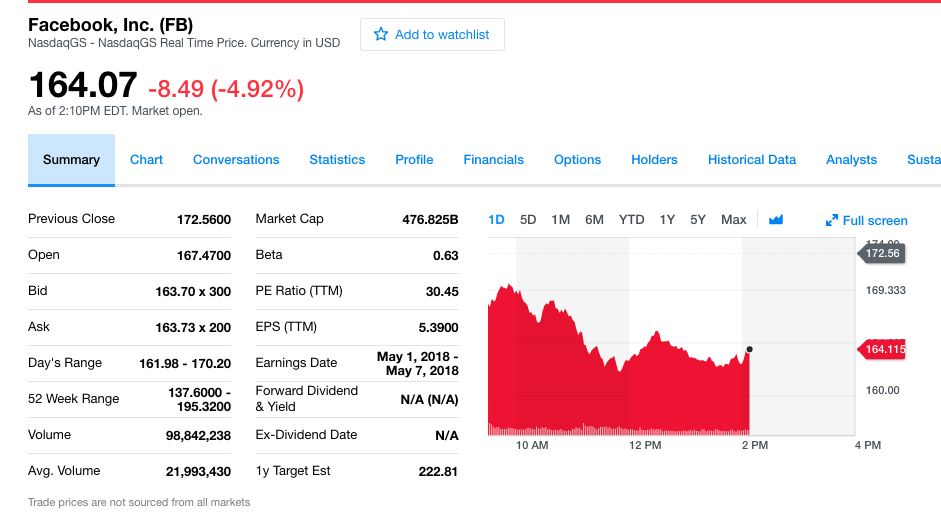

Facebook is having a bad day… for the second day in a row. Following the Cambridge Analytica debacle, Facebook shares (NASDAQ:FB) are currently trading at $164.07, down 4.9 percent compared to yesterday’s closing price of $172.56.

More importantly, if you look at Monday and Tuesday combined, Facebook shares are down 11.4 percent compared to Friday’s closing price of $185.09. In other words, Facebook was worth $537.69 billion on Friday evening when it comes to market capitalization. And Facebook is now worth $476.83 billion.

That’s how you lose $60 billion in market cap.

Facebook hired a forensics firm to investigate Cambridge Analytica as stock falls 7%

Hoping to tamp down the furor that erupted over reports that its user data was improperly acquired by Cambridge Analytica, Facebook has hired the digital forensics firm Stroz Friedberg to perform an audit on the political consulting and marketing firm.

In a statement, Facebook said that Cambridge Analytica has agreed to comply and give Stroz Friedberg access to their servers and systems.

Facebook has also reached out to the whistleblower, Christopher Wylie, and Aleksandr Kogan, the Cambridge University professor who developed an application that collected data that he then sold to Cambridge Analytica.

Kogan has consented to the audit, but Wylie, who has positioned himself as one of the architects for the data collection scheme before becoming a whistleblower, declined, according to Facebook.

The move comes after a brutal day for Facebook’s stock on the Nasdaq stock exchange. Facebook shares plummeted 7 percent, erasing roughly $40 billion in market capitalization amid fears that the growing scandal could lead to greater regulation of the social media juggernaut.

Indeed both the Dow Jones Industrial Average and the Nasdaq fell sharply as worries over increased regulations for technology companies ricocheted around trading floors, forcing a sell-off.

“This is part of a comprehensive internal and external review that we are conducting to determine the accuracy of the claims that the Facebook data in question still exists. This is data Cambridge Analytica, SCL, Mr. Wylie, and Mr. Kogan certified to Facebook had been destroyed. If this data still exists, it would be a grave violation of Facebook’s policies and an unacceptable violation of trust and the commitments these groups made,” Facebook said in a statement.

However, as more than one Twitter user noted, this is an instance where they’re trying to close Pandora’s Box but the only thing that the company has left inside is… hope.

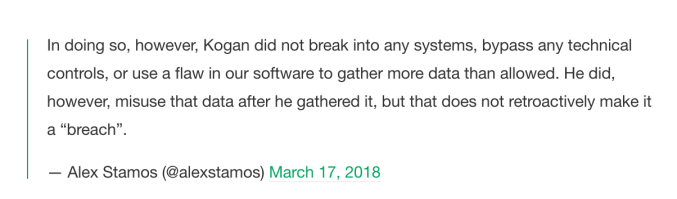

The bigger issue is that Facebook had known about the data leak as early as two years ago, but did nothing to inform its users — because the violation was not a “breach” of Facebook’s security protocols.

Facebook’s own argument for the protections it now has in place is a sign of its too-little, too-late response to a problem it created for itself with its initial policies.

“We are moving aggressively to determine the accuracy of these claims. We remain committed to vigorously enforcing our policies to protect people’s information. We also want to be clear that today when developers create apps that ask for certain information from people, we conduct a robust review to identify potential policy violations and to assess whether the app has a legitimate use for the data,” the company said in a statement. “We actually reject a significant number of apps through this process. Kogan’s app would not be permitted access to detailed friends’ data today.”

It doesn’t take a billionaire Harvard dropout genius to know that allowing third parties to access personal data without an individual’s consent is shady. And that’s what Facebook’s policies used to allow by letting Facebook “friends” basically authorize the use of a user’s personal data for them.

As we noted when the API changes first took effect in 2015:

Apps don’t have to delete data they’ve already pulled. If someone gave your data to an app, it could go on using it. However, if you request that a developer delete your data, it has to. However, how you submit those requests could be through a form, via email, or in other ways that vary app to app. You can also always go to your App Privacy Settings and remove permissions for an app to pull more data about you in the future.

Facebook shares drop 4.4 percent following Cambridge Analytica debacle

Facebook has been at the center of a hectic debate about Cambridge Analytica and the company’s improper use of Facebook data. As a result, Facebook shares (NASDAQ:FB) opened at $177.01, down 4.4 percent compared to Friday’s closing price of $185.09.

Share prices are still going down after the opening bell. NASDAQ as a whole is more or less flat — the stock market opened down 0.1 percent. It’s worth noting that Facebook shares have been doing well recently:

On Thursday, Facebook suspended Cambridge Analytica from its platform. The political data analytics used Facebook data to help Donald Trump’s presidential campaign.

The main issue is that the company developed an app called an app called “thisisyourdigitallife” to harvest user data. While many people thought they were downloading a fairly harmless personality quiz app, Cambridge Analytica was using Facebook’s API to gather data about the users of this app, but also the friends of the users.

While Facebook shut down the API that gave friends’ data to apps last year, it’s already too late. Developers have improperly used Facebook’s API to influence elections.

That’s why many people think regulation on tech companies is now inevitable, which could hurt Facebook’s bottom line.

Facebook has suspended the account of the whistleblower who exposed Cambridge Analytica

Tech hath no fury like a multi-billion dollar social media giant scorned.

In the latest turn of the developing scandal around how Facebook’s user data wound up in the hands of Cambridge Analytica — for use in the in development in psychographic profiles that may or may not have played a part in the election victory of Donald Trump — the company has taken the unusual step of suspending the account of the whistleblower who helped expose the issues.

In a fantastic profile in The Guardian, Wylie revealed himself to be the architect of the technology that Cambridge Analytica used to develop targeted advertising strategies that arguably helped sway the U.S. presidential election.

A self-described gay, Canadian vegan, Wylie eventually became — as he told The Guardian — the developer of “Steve Bannon’s psychological warfare mindfuck tool.”

The goal, as The Guardian reported, was to combine social media’s reach with big data analytical tools to create psychographic profiles that could then be manipulated in what Bannon and Cambridge Analytica investor Robert Mercer allegedly referred to as a military-style psychological operations campaign — targeting U.S. voters.

In a series of Tweets late Saturday, Wylie’s former employer, Cambridge Analytica, took issue with Wylie’s characterization of events (and much of the reporting around the stories from The Times and The Guardian).

Meanwhile, Cadwalldr noted on Twitter earlier today she’d received a phone call from the aggrieved whistleblower.

Facebook has since weighed in with a statement of its own, telling media outlets:

“Mr. Wylie has refused to cooperate with us until we lift the suspension on his account. Given he said he ‘exploited Facebook to harvest millions of people’s profiles,’ we cannot do this at this time.

“We are in the process of conducting a comprehensive internal and external review as we work to determine the accuracy of the claims that the Facebook data in question still exists. That is where our focus lies as we remain committed to vigorously enforcing our policies to protect people’s information.”

Regulators in the UK are also calling for more hearings into Facebook and Cambridge Analytica

As more details emerge about Cambridge Analytica’s use of Facebook data in the U.S. presidential election, members of Parliament in the UK are joining congressional leadership in the U.S. to call for a deeper investigation and potential regulatory action.

The Chair of parliamentary committee investigating “fake news”, the conservative MP Damian Collins, accused both Cambridge Analytica and Facebook of misleading his committee’s investigation in a statement early Sunday morning indicating that both companies would be called in for more questioning.

“Alexander Nix denied to the Committee last month that his company had received any data from the Global Science Research company (GSR). From the evidence that has been published by The Guardian and The Observer this weekend, it seems clear that he has deliberately mislead the Committee and Parliament by giving false statements,” Collins wrote in a statement to the press. “We will be contacting Alexander Nix next week asking him to explain his comments, and answer further questions relating to the links between GSR and Cambridge Analytica, and its associate companies.”

On Friday, Facebook announced that it had suspended the account of Cambridge Analytica for violating the social media company’s terms and conditions by obtaining user data from a third party source without users’ permissions.

The announcement, made late Friday night, was designed to preempt reports published by The New York Times and The Guardian that would have exposed the fact that Cambridge Analytica had obtained information on 50 million Facebook users — and that Facebook had known about the improper availability of that user data for two years.

The use or abuse of that data by Cambridge Analytica in work that it had done with Donald Trump’s campaign for President in 2016 and potentially for other businesses in the run up to the election is at the heart of Donal

Before basically verifying the accuracy of the story, Facebook had threatened both The Times and The Guardian with legal action to try and kill it.

The company’s response to the reports aren’t impressing anyone — and could land more than just its chief counsel in the hot seat.

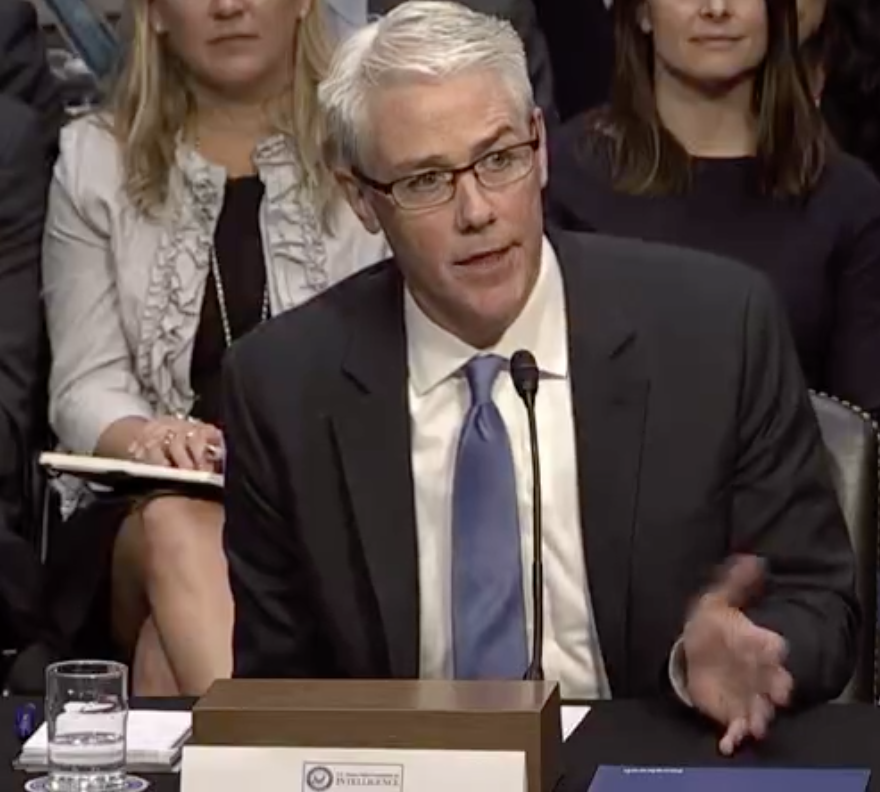

Facebook Chief Legal Officer Colin Stretch

“We have repeatedly asked Facebook about how companies acquire and hold on to user data from their site, and in particular whether data had been taken from people without their consent. Their answers have consistently understated this risk, and have also been misleading to the Committee,” Collins wrote.

He went on to accuse Facebook of “deliberately answering straight questions from the committee” and failing to supply the Committee with evidence relating to “the relationship between Facebook and Cambridge Analytica.” Evidence that had been promised when members of Parliament went to Washington to quiz Facebook about its role in various political campaigns in the UK.

“I will be writing to Mark Zuckerberg asking that either he, or another senior executive from the company, appear to give evidence in front of the Committee as part our inquiry. It is not acceptable that they have previously sent witnesses who seek to avoid asking difficult questions by claiming not to know the answers. This also creates a false reassurance that Facebook’s stated policies are always robust and effectively policed,” Collins wrote.

“We need to hear from people who can speak about Facebook from a position of authority that requires them to know the truth. The reputation of this company is being damaged by stealth, because of their constant failure to respond with clarity and authority to the questions of genuine public interest that are being directed to them. Someone has to take responsibility for this. It’s time for Mark Zuckerberg to stop hiding behind his Facebook page.”

Facebook’s latest privacy debacle stirs up more regulatory interest from lawmakers

Facebook’s late Friday disclosure that a data analytics company with ties to the Trump campaign improperly obtained — and then failed to destroy — the private data of 50 million users is generating more unwanted attention from politicians, some of whom were already beating the drums of regulation in the company’s direction.

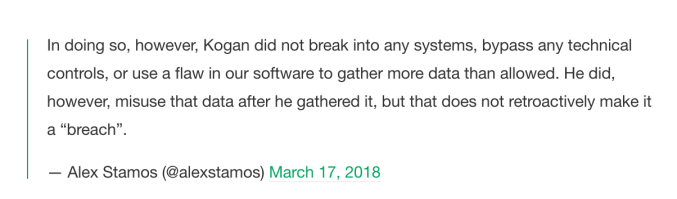

On Saturday morning, Facebook dove into the semantics of its disclosure, arguing against wording in the New York Times story the company was attempting to get out in front of that referred to the incident as a breach. Most of this happened on the Twitter account of Facebook chief security officer Alex Stamos before Stamos took down his tweets and the gist of the conversation made its way into an update to Facebook’s official post.

“People knowingly provided their information, no systems were infiltrated, and no passwords or sensitive pieces of information were stolen or hacked,” the added language argued.

While the language is up for debate, lawmakers don’t appear to be looking kindly on Facebook’s arguably legitimate effort to sidestep data breach notification laws that, were this a proper hack, could have required the company to disclose that it lost track of the data of 50 million users, only 270,000 of which consented to data sharing to the third party app involved. (In April of 2015, Facebook changed its policy, shutting down the API that shared friends data with third-party Facebook apps that they did not consent to sharing in the first place.)

While most lawmakers and politicians haven’t crafted formal statements yet (expect a landslide of those on Monday), a few are weighing in. Minnesota Senator Amy Klobuchar calling for Facebook’s chief executive — and not just its counsel — to appear before the Senate Judiciary committee.

Senator Mark Warner, a prominent figure in tech’s role in enabling Russian interference in the 2016 U.S. election, used the incident to call attention to a piece of bipartisan legislation called the Honest Ads Act, designed to “prevent foreign interference in future elections and improve the transparency of online political advertisements.”

“This is more evidence that the online political advertising market is essentially the Wild West,” Warner said in a statement. “Whether it’s allowing Russians to purchase political ads, or extensive micro-targeting based on ill-gotten user data, it’s clear that, left unregulated, this market will continue to be prone to deception and lacking in transparency.”

That call for transparency was echoed Saturday by Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey who announced that her office would be launching an investigation into the situation. “Massachusetts residents deserve answers immediately from Facebook and Cambridge Analytica,” Healey tweeted. TechCrunch has reached out to Healey’s office for additional information.

On Cambridge Analytica’s side, it looks possible that the company may have violated Federal Election Commission laws forbidding foreign participation in domestic U.S. elections. The FEC enforces a “broad prohibition on foreign national activity in connection with elections in the United States.”

“Now is a time of reckoning for all tech and internet companies to truly consider their impact on democracies worldwide,” said Nuala O’Connor, President of the Center for Democracy & Technology. “Internet users in the U.S. are left incredibly vulnerable to this sort of abuse because of the lack of comprehensive data protection and privacy laws, which leaves this data unprotected.”

Just what lawmakers intend to do about big tech’s latest privacy debacle will be more clear come Monday, but the chorus calling for regulation is likely to grow louder from here on out.

Trump campaign-linked data firm Cambridge Analytica reportedly collected info on 50M Facebook profiles

Facebook said on Thursday it had suspended a data analytics firm associated with the Trump campaign, but may have indeed greatly downplayed the scale of the data that firm actually had access to, according to a new report in The New York Times.

Cambridge Analytica had worked with University of Cambridge psychology professor named Dr. Aleksandr Kogan, who had developed an app called “thisisyourdigitallife” and obtained user information — which the Times is reporting scooped up information on profiles of as many as 50 million users. Late Friday, Facebook acknowledged that 270,000 people downloaded the app, which used Facebook Login and granted access to users’ geographic information. But just one person — with hundreds of friends — allowing access to a personal information through an app, circa 2014, may have had a much larger impact than it does today.

In the earlier stages of a company, it’s possible that policies are not rigorous enough and the guardrails on various APIs are not robust enough that this kind of information can just get out in the open without additional scrutiny, allowing firms to take advantage of those shortcomings. Facebook executives, on Twitter no less, were quick to be clear that this wasn’t a breach — though the argument is that it is, indeed, might not be considered a breach in the traditional sense of the word. But, here’s what Facebook chief security officer Alex Stamos said:

Update: Stamos deleted his Tweets. The above is a screenshot of his previous tweet. Here’s his explanation.

Prior to deleting his tweets, Stamos posted a long thread that explained the nitty gritty of the situation, which is that around the time of the quiz, the Facebook API allowed developers to see a much wider swath of the data that’s available now. Those APIs were updated in 2015 to remove the ability to see that kind of friend data, a move Stamos said was “controversial” with app developers at the time. These policies in reality are constantly evolving and trying to hit a moving target, especially at the scale of Facebook with more than 2 billion monthly active users. That being said, Trump’s margin of victory in terms of the final vote counts in pivotal states was narrow, so information on the right 50 million people could have made a huge difference.

While Facebook was a publicly-traded company, with a fiduciary duty to its shareholders in 2014 to not have massive screwups and probably a lot more responsibility to keep this kind of information in check, it’s hardly alone in that respect. We’ve seen instances of those missing guardrails to access in many companies and used in many inappropriate ways, like Uber’s “god view” and Lyft’s own troubles. It’s definitely a different situation, but when a company is in growth mode, these kinds of guardrails might simply not be a high priority. That might be especially true when the data sets become increasingly large and simply managing them becomes a huge technical effort. Facebook had 1.39 billion monthly active users by the end of Q4 2014.

To be sure, It does not make the scale of this incident any less severe or important.

Facebook came out with a statement late Friday that it had suspended the account of Strategic Communication Laboratories and its political data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica. However it appears it still may have again downplayed the total scale of the data Kogan had acquired from Facebook users. The Times said it downplayed the scope of the leak and “questioned whether any data still remained out of its controls” throughout a week of inquiries.

We reached out to Facebook for some additional information, and will update when we hear back. But for the time being Facebook executives seem to continue to follow a trend of explaining themselves on Twitter, so we’ll take that as the current statement for Facebook.

Facebook suspends Cambridge Analytica, the data analysis firm that worked on the Trump campaign

Facebook announced late Friday that it had suspended the account of Strategic Communication Laboratories, and its political data analytics firm Cambridge Analytica — which used Facebook data to target voters for President Donald Trump’s campaign in the 2016 election. In a statement released by Paul Grewal, the company’s vice president and deputy general counsel, Facebook explained that the suspension was the result of a violation of its platform policies. The company noted that the very unusual step of a public blog post explaining the decision to act against Cambridge Analytica was due to “the public prominence of this organization.”

Facebook claims that back in 2015 Cambridge Analytica obtained Facebook user information without approval from the social network through work the company did with a University of Cambridge psychology professor named Dr. Aleksandr Kogan. Kogan developed an app called “thisisyourdigitallife” that purported to offer a personality prediction in the form of “a research app used by psychologists.”

Apparently around 270,000 people downloaded the app, which used Facebook Login and granted Kogan access to users’ geographic information, content they had liked, and limited information about users’ friends. While Kogan’s method of obtaining personal information aligned with Facebook’s policies, “he did not subsequently abide by our rules,” Grewal stated in the Facebook post.

“By passing information on to a third party, including SCL/Cambridge Analytica and Christopher Wylie of Eunoia Technologies, he violated our platform policies. When we learned of this violation in 2015, we removed his app from Facebook and demanded certifications from Kogan and all parties he had given data to that the information had been destroyed. Cambridge Analytica, Kogan and Wylie all certified to us that they destroyed the data.”

Facebook said it first identified the violation in 2015 and took action — apparently without informing users of the violation. The company demanded that Kogan, Cambridge Analytica and Wylie certify that they had destroyed the information.

Over the past few days, Facebook said it received reports (from sources it would not identify) that not all of the data Cambridge Analytica, Kogan, and Wylie collected had been deleted. While Facebook investigates the matter further, the company said it had taken the step to suspend the Cambridge Analytica account as well as the accounts of Kogan and Wylie.

Depending on who you ask, UK-based Cambridge Analytica either played a pivotal role in the U.S. presidential election or cooked up an effective marketing myth to spin into future business. Last year, a handful of former Trump aides and Republican consultants dismissed the potency of Cambridge Analytica’s so-called secret sauce as “exaggerated” in a profile by the New York Times. A May 2017 profile in the Guardian that painted the Robert Mercer-funded data company as shadowy and all-powerful resulted in legal action on behalf of Cambridge Analytica. Last October, the Daily Beast reported that Cambridge Analytica’s chief executive Alexander Nix contacted Wikileaks’ Julian Assange with an offer to help disseminate Hillary Clinton’s controversial missing emails.

In an interview with TechCrunch late last year, Nix said that his company had detailed hundreds of thousands of profiles of Americans throughout 2014 and 2015 (the time when the company was working with Sen. Ted Cruz on his presidential campaign).

…We used psychographics all through the 2014 midterms. We used psychographics all through the Cruz and Carson primaries. But when we got to Trump’s campaign in June 2016, whenever it was, there it was there was five and a half months till the elections. We just didn’t have the time to rollout that survey. I mean, Christ, we had to build all the IT, all the infrastructure. There was nothing. There was 30 people on his campaign. Thirty. Even Walker it had 160 (it’s probably why he went bust). And he was the first to crash out. So as I’ve said to other of your [journalist] colleagues, clearly there’s psychographic data that’s baked-in to legacy models that we built before, because we’re not reinventing the wheel. [We’ve been] using models that are based on models, that are based on models, and we’ve been building these models for nearly four years. And all of those models had psychographics in them. But did we go out and rollout a long form quantitive psychographics survey specifically for Trump supporters? No. We just didn’t have time. We just couldn’t do that.

The key implication here is that data leveraged in the Trump campaign could have originated with Kogan before being shared to Cambridge Analytica in violation of Facebook policy. The other implication is that Cambridge Analytica may not have destroyed that data back in 2015.

The tools that Cambridge Analytica deployed have been at the heart of recent criticism of Facebook’s approach to handling advertising and promoted posts on the social media platform.

Nix credits the fact that advertising was ahead of most political messaging and that traditional political operatives hadn’t figured out that the tools used for creating ad campaigns could be so effective in the political arena.

“There’s no question that the marketing and advertising world is ahead of the political marketing the political communications world,” Nix told TechCrunch last year. “…There are some things which [are] best practice digital advertising, best practice communications which we’re taking from the commercial world and are bringing into politics.”

Responding to the allegations, Cambridge Analytica sent the following statement.

In 2014, SCL Elections contracted Dr. Kogan via his company Global Science Research (GSR) to undertake a large scale research project in the US. GSR was contractually committed to only obtain data in accordance with the UK Data Protection Act and to seek the informed consent of each respondent. GSR were also contractually the Data Controller (as per Section 1(1) of the Data Protection Act) for any collected data. The language in the SCL Elections contract with GSR is explicit on these points. GSR subsequently obtained Facebook data via an API provided by Facebook. When it subsequently became clear that the data had not been obtained by GSR in line with Facebook’s terms of service, SCL Elections deleted all data it had received from GSR. For the avoidance of doubt, no data from GSR was used in the work we did in the 2016 US presidential election.

Under Section 55 of the Data Protection Act (Unlawful obtaining etc. of personal data), a criminal offense has not been committed if a person has acted in the reasonable belief that he had in law the right to obtain data. GSR was a company led by a seemingly reputable academic at an internationally renowned institution who made explicit contractual commitments to us regarding the its legal authority to license data to SCL Elections. It would be entirely incorrect to attempt to claim that SCL Elections

illegally acquired Facebook data. Indeed SCL Elections worked with Facebook over this period to ensure that they were satisfied that SCL Elections had not knowingly breached any of Facebook’s Terms of Service and also provided a signed statement to confirm that all Facebook data and their derivatives had been deleted.

Cambridge Analytica and SCL Elections do not use or hold Facebook data.

Cambridge Analytica CEO talks to TechCrunch about Trump, Hillary and the future

A few weeks ago I met with, and interviewed, Alexander Nix, the CEO of Cambridge Analytica. His company has been credited with helping Donald Trump win the U.S. presidency. It’s also been associated with many other controversial political campaigns globally and accused by some of aiding the U.K.’s exit from the EU. He addresses all of these subjects in detail (a shorter summary is here).

The interview, which was recorded, was conducted in private at the IT Arena conference in Lviv, Ukraine.

This is the transcript of the interview, which was 50 minutes long:

Mike Butcher (MB):

You think that digital advertising agencies have ‘got it coming’, such as the WPPs of this world. What do you mean by that?

Alexander Nix (Nix):

Actually, probably not digital advertising agencies because they’re more progressive. I’m really looking at the old school traditional creative-led agencies. [For example] within WPP, obviously Martin (Sorrell) has made a huge effort to pivot his business. He’s making a huge effort every day, acquiring 40+ companies a year, something like that. But when you look at the traditional approach to advertising, which is fundamentally driven by guesswork, albeit very intuitive and experienced guesswork… The advert I was thinking about… do you remember the Cadbury’s advert of a gorilla playing the drums? I mean who could have known that that was going to be a national success? I mean, you’re telling me they went and opinion-surveyed 5,000 people and then decided to make a gorilla advert? Of course they didn’t! They just ‘wing’d it’ and it happened to push people’s buttons and it was a great success. Well, that sort of advertising is going to be replaced by highly targeted, very personalized advertising, and that has to be data-driven. That’s not replacing of creativity, that’s using data to augment creativity. Data first then creativity. It’s linear.

MB:

Looking at the figures on your website you said you drove 1.5% increase in favourability among people who saw your [US election campaign] ads. Not everyone who becomes more favorable after seeing that ad is going to change their vote for instance. Most of them had been planning to vote for Trump already or [the ad] wouldn’t make enough difference to stop them voting for Hillary. But it might for influence a very small percentage of the electorate. That might have been enough to swing Michigan but not the whole election.

Nix:

How many states was the election won over? Four? I mean, winning Michigan, Pennsylvania, Wisconsin, Florida… That was pretty much it.

MB:

Because it came down the electoral college that you were targeting?

Nix:

It always comes down to that. It’s always the roadmap to 270. That changes every day. You go into the election: “We’re thinking okay these are 12-14 battleground states.” After six weeks you’re like: “Christ. That one’s dead. Got to move. How do how do we get there how do we do the sums to get back to where we want to be?” You know, you don’t need to and you can’t afford to focus on 50 states. You’re looking at… you know you’re going to win these ones you’re never going to win those, so how do you get to where you want to go?

MB:

You said the people who saw Cambridge Analytica adverts… the likelihood of voting for Trump increased by 1 percent. Isn’t it that one of the company’s claims?

Nix:

Google’s study was based on the impact of our digital campaign. It said [there was an ] 11.3 percent increase in favourability for Trump. An 8.3 percent increase in intent to vote for Trump. These are significant numbers.

MB:

So in 2017 you can claim you have psychological profiles of 220m U.S. citizens based on five thousand separate data sets?

Nix:

It actually works slightly different to that. We went out and we started to roll out a long form quantitive survey to probe psychographics.

So we had hundreds of thousands of Americans fill out this survey. Completely independent from that we went and collected hundreds and then thousands of data points on every adult 230 million Americans.

MB:

This was publicly available data?

Nix:

This is publicly available data, this is client data, this is an aggregated third-party data. All sorts of data. In fact, we’re always acquiring more. Every day we have teams looking for new data sets.

Let’s say based on the personality survey that we’ve identified five personality types, only, for the whole of America. And let’s say for each personality type we’ve got a hundred thousand people of type A and Type B and Type C. Well, we’ll look at the hundred thousand type A personalities, and then we’ll have a look at the corresponding data points that we have on those hundred thousand people. We’ll have a look at what attributes they have in common and then we’ll build a model based on that. So if we identify that all type A personalities drive a lemon yellow car and wear Wellington boots and have a dog and three children and whatever, we can then make a prediction about everyone else in the universe who has a yellow car, a dog, Wellington boots and say well they’re very likely to also have a type A personality based on their data.

The best example I can give you [of] building a model [is that] in England we have a stereotype for conservatives, rural conservatives. They wear a barber [jacket], that Nigel Farage type. They wear a Barber and Wellington boots and have a Labrador, and they all went to private school, and they are therefore going to vote Tory. A stereotype but stereotypes are based on something. Well, that was four data points. Actually, it’s quite accurate in England. Imagine if you had 40 data points, or 400 and you extrapolated that they drive Land Rover, they like shooting, they both work in merchant banking and so on. You start to build up those data points and you can very accurately say “Well, I don’t know this person’s party political affiliation, but I do know they have a Barber and a Land Rover and a dog and they like shooting and work in merchant banking, therefore, they’re likely to be a Tory.

MB:

So you call this psychographics?

Nix:

Yes.

MB:

But did you use psychographics in the Trump campaign or didn’t you?

Nix:

No, we didn’t. We’ve been absolutely, incredibly clear about this. We used psychographics all through the 2014 midterms. We used psychographics all through the Cruz and Carson primaries. But when we got to Trump’s campaign in June 2016, whenever it was, there it was there was five and a half months till the elections. We just didn’t have the time to roll out that survey. I mean, Christ, we had to build all the IT, all the infrastructure. There was nothing. There was 30 people on his campaign. Thirty. Even Walker it had 160 (it’s probably why he went bust). And he was the first to crash out. So as I’ve said to other of your [journalist] colleagues, clearly there’s psychographic data that’s baked-in to legacy models that we built before, because we’re not reinventing the wheel. [We’ve been] using models that are based on models, that are based on models, and we’ve been building these models for nearly four years. And all of those models had psychographics in them. But did we go out and roll out a long form quantitive psychographics survey specifically for Trump supporters? No. We just didn’t have time. We just couldn’t do that.

MB:

You say you’ve been building this data since the late 90s. We know Facebook’s terms of service in 2006 were quite different to what they are now. And actually there was quite a lot of data — scrape is probably too blunt a word — but data which you could pull out of Facebook then that you can’t pull out now. Was it the case that you had huge data sets on these people before the door started to close on the [Facebook] terms of service?

Nix:

Well, actually let me correct you. The company started in the early 90s or late 80s. We were a behavioural science company. We didn’t pivot into data analytics till 2012. So, all the data that we collected pre-2012, which was done by the British company SBL group, was collected through quantitive and qualitative research on the ground. Our modus operandi was to go and speak to, say, 100,000 people and start to use that to build on models.

MB:

Speak to them how? Via call centre surveys?

Nix:

Depending on the country… I mean, in America, yes, call centres, the Internet where possible, face to face… But in a country like Nigeria you know you just have teams and teams of students going out there knocking on doors.

MB:

So you’re doing that in Nigeria?

Nix:

Well, we’ve been doing that since our first election was 1994 for Mandela/ANC and since then we’ve done multiple elections every year.

MB:

Another claim CA makes is that you raised nearly $27m for Trump from 950,000 email addresses?

Nix:

No those are two separate things. We ran a ‘small-dollar’ fundraising program. So what we did was we used our data to identify core Trump supporters. These are the diehard Trump supporters of which we estimate there are about 37-38 million people in America. And we then targeted them with a with a donor solicitation or small dollars solicitation campaign to ask them to send donations in. And we built all the data and all the mechanisms to do that. We raised that $27m within the first month of starting work. In total, obviously, that program went on to raise hundreds and millions of dollars.

MB:

Would you consider that to be being pivotal for their campaign?

Nix:

Well, I think I think it was extremely pivotal because when Trump won the nomination he had very, very little money. And although he talked about putting a bit of money in himself, and he did put some money and some in as cash, most of it as loans, that’s my understanding, you know, you were competing against the machine and she had dollars coming out of everywhere.

Also, there was a huge “Never Trump” faction in America. Most of the Republicans didn’t support him, and even those who ended up working for him didn’t support him. So the RNC, the Republican National Committee, didn’t support him. Ultimately they pivoted. A lot of the key RNC members were part of the “Never Trump” faction. They were behind his back. They were trying to destroy him. And eventually they all they did a complete U-turn. Part of the reason why we were thrust into such a prominent role in this campaign is because none of the vendors would support him.

[Being among] Republican vender’s is an incredibly hostile environment. They were looking at this candidate and they said “Well, first and foremost we don’t like him.” A typical presidential campaign will probably have five or eight different companies support it. You’ll have a pollster, you’ll have a digital agency, you’ll have a TV agency, you’ll have a research firm. And then the campaign manager and the campaign committee will choose the best pollsters and the best thing or their best friend or however they figure these things out.

Well, Trump won the nomination and all the Republicans said “Well, he’s going to get murdered by Hillary. If we work for him, the establishment of the RNC is going to hate us. We’ll never get another dollar in U.S. politics again. So we’ll make a quick buck today, but it’s going to kill our career tomorrow.” So a lot of them are like “we’d never want to touch this.” So rather than having multiple vendors servicing his campaign, as is traditional, as Hillary had, we walked in there and said “We’ll do your data analytics.” And they were like: “There’s no one doing research.” [We said] we will do your research. “There’s no doing digital” We will do digital. “There’s no one doing TV.” “We’ll do your TV.” We’ll do your donations. And so overnight it went from being originally just data, to end to end.

MB:

Did you believe you were betting the farm, as it were, on the campaign?

Nix:

Look, from my perspective it was an easy bet to make. It was a win-win. I couldn’t see the downside. I thought even if Trump didn’t prevail if he didn’t win the election.

Look, we’re a British firm that was trying to break into the most competitive political market in the world. And you know, we had some mixed press. But what really irritates me is when journalists go to get a quote about our work. And someone says “We worked with Cambridge Analytica and their work didn’t really provide anything. It was rubbish.” And then you have a look at who the quote was from and it’s from a direct competitor!

And this is what the journalists haven’t quite figured out. A lot of the people that they speak to are people whose lunch we’re eating. We walked into [the US] market. We’re competing with all the data teams. We’re competing with all the digital teams, all the TV teams, all the research teams. You’ve seen House of Cards. It’s like that. It’s the most vicious aggressive political culture both at the candidate level, that Trump is now finding out. At the campaign manager, GC level and at the vendor level. It’s a bloodbath. The knives… [are out]. In DC, everyone’s fucking everyone else.

You see three quotes they’re all from people whose business you’ve stolen. They’re saying things like we came across “Cambridge Analytica. It’s All snake oil” [and it’s from] our biggest rival.

MB:

Do you think there’s a mischaracterization of the tools used by targeted advertising campaigns, or so-called ‘custom audience’ campaigns, as being described as “dark advertising” campaigns?

Nix:

There’s no question that the marketing and advertising world is ahead of the political marketing the political communications world. And there are some things that I would definitely [say] I’m very proud of that we’re doing which are innovative. And there are some things which is best practice digital advertising, best practice communications which we’re taking from the commercial world and are bringing into politics.

Advertising agencies are using some of these techniques on a national scale. For us it’s been very refreshing, really breaking into the commercial and brand space… walking into a campaign where you’re basically trying to educate the market on stuff they simply don’t understand. You walk into a sophisticated brand or into an advertising agency, and the conversation [is sophisticated] You go straight down to: “Ah, so you’re doing a programmatic campaign, you can augment that with some linear optimized data… they understand it.” They know it’s their world, and now it comes down to the nuances. “So what exactly are you doing that’s going to be a bit more effective and give us an extra 3 percent or 4 percent there.” It’s a delight. You know these are professionals who really get this world and that’s where we want to be operating.

MB:

Do you regret the way your own business is being presented in the media?

Nix:

If there’s any testament to what’s driving the media just have a glance at Hillary Clinton’s recent book. The liberal press are supporting their candidate. They got fairly beaten and they’re lashing out and trying to destroy every single person and every company that contributed to that defeat. Hillary simply cannot come to terms with it. She’s a woman in denial. The liberal press [characterized Cambridge Analytica] as “witchcraft, they treat it is “voodoo” and now it’s Russia’s fault! They just cannot accept the fact that Hillary was such an unpopular, such a divisive candidate. She failed to mobilize her base and people didn’t fundamentally trust her. Rather than looking in the mirror, they much prefer to beat up Cambridge [Analytica] beat up Trump, beat up anyone else. Anything but accept the fact that their candidate wasn’t what the people wanted to vote for.

MB:

Would you use your own methods to improve your own public image?A marketing campaign for yourself to create a better image for your own company?

Nix:

Would we rollout a national behavioral micro-targeting program to promote Cambridge Analytica? It probably wouldn’t really achieve what we’re trying to do. I mean actually, I’m just ‘dotting the I’s and crossing the T’s’ on a book which talks about our methodology and our approach to communications and I was speaking to the publisher about whether we should target that. It’s a book hasn’t been published yet, it’ll come out next month, just talking really in quite technical terms about how communication is changing, what how technology is impacting that, what data is doing to advertising and political campaigns and then using a lot of case studies with a lot of real examples of artwork and targeting and psychographics and so forth to illustrate them. We were toying with the idea of [a campaign]. But I think it’s too complex to try and use our techniques to promote a book. It was more of a thought exercise right. It would mean having multiple versions multiple titles multiple dust sheets.

MB:

A/B testing for a book? Is the book coming out in the New Year?

Nix:

It’s coming out in Germany first because it was a German publisher that approached us. It will be coming out in about the next month or so and then later in the U.K.

MB:

It is going to be about the company or methodology. Or your worldview?

Nix:

The English title is not confirmed yet but I think it will be something like “Mad men to maths men”. It’s going to be [about] the evolution of the advertising industry, how data, how psychology, how digital is changing an industry that really hasn’t changed very much. And what that disruption means in terms of an industry of you know multi-billion dollar industry and illustrating different campaigns that we’ve done to show the effectiveness of that.

MB:

On Brexit there were headlines such as ‘The great Brexit robbery, our democracy was hijacked’. How do you react to those?

Nix:

Well, look, I mean you’re implying therefore that we were involved in Brexit and part of that “robbery”. We’ve been, again, crystal clear to all media including The Guardian, who really propagated this story from day one, based on nothing. Carole Cadwalladr has made it her personal mission to come after us again, living in denial about the outcome of the election. She cannot accept that the British people wanted to leave Europe and she’s made it her mission to vilify us. We did not work on Brexit. We didn’t do a little bit of work. We didn’t do a lot of work. We did no work on Brexit. We were not involved in the campaign for either Leave.eu or Vote Leave, at all. And we have been crystal clear on this which is why we’re going to be taking them to court and we’re going to settle.

MB:

Why do you think you became associated with it then?

Nix:

Well because before the campaigns were launched we were approached by a number of different campaigns, pro and against, to discuss whether there might be a role for us on Brexit. And we had a number of discussions. Obviously, these discussions made their way into the public forum but we meet with hundreds of companies every year and talk about business opportunities. That doesn’t mean you engage with them doesn’t mean you contract with them and it certainly doesn’t mean that you work for them. But The Guardian came out with one or two data points and then created an entire narrative around that that was pure fiction. That went viral and then every other newspaper [piled into it]. If you tell a lie often enough it becomes truth. But even after we came out and denied that again and again and again they just kept propagating the same message.

MB:

But you are working in other campaigns. There’s been some controversy about Kenya and South Africa for instance. How do you react to those?

Nix:

Well, you are talking about Bell Pottinger, [which has] paid the consequences for some bad decisions.

MB:

Did you work on those campaigns?

Nix:

No, we weren’t involved with the actors. We weren’t involved with Bell Pottinger, we weren’t involved with the Guptas. In fact, I know very little about that. And I really can’t make a commentary on what happened. I know only what I’ve read in the paper.

MB:

You worked on the Kenya campaign?

Nix:

We’ve worked all across Africa.

MB:

Kenya?

Nix:

Well, let’s wait till the election’s over because we never talk about elections that live, generally, as a rule of thumb. But I can tell you that we worked in Kenya in 2013 on the last election for Kenyatta. That’s well documented. I can speak to that. Look, Kenyatta won by 12 points and there were some few irregularities, from what I’ve read, in the way that the election oversight committee… [granted] some of the tenders [for] election equipment. The opposition used these irregularities to challenge the outcome of the election. I think had this been a “Florida” years ago when it came down to half a percent, ok. But when you’re talking about a 12 percent victory I think that the court’s decision to hold this [new] election was a dreadful decision. I think that it is going to result in dreadful bloodshed, horrific violence. If Kenyatta for any reason doesn’t win this election then his supporters are going to feel robbed. And if Odinga’s people don’t, they’re going to feel that he’s cheated again because that’s the perception that Odinga is put out into the public domain.

I can’t see this ending well. I think just for the sake of Kenya, for peace in the region, I think it’s a dreadful decision. I actually can’t even see this election being resolved in the next month. I think it’s going to drag on. So, I think the court’s decision was shortsighted.

MB:

What’s your answer to critics who claimed that you’ve worked on behalf of the Russian government or third party actors connect to them? Either for specifically in relation to Trump’s campaign or to other campaigns.

Nix:

We’ve never been asked directly. No one of authority has leveled any direct criticisms to us and, certainly, no one has suggested that we’d been or alleged that we’d been involved as far as I’m aware. We’re not under investigation by anyone. We are helping wherever we can with the understandings of the campaign, like everyone else in the campaign, but there’s no investigation into Cambridge [Analytica].

MB:

Isn’t the U.S. Congress investigating you in connection with Russian attempts to interfere with the election?

Nix:

No, it’s not. The US Congress is undertaking…

MB:

The Atlantic magazine reported it.

Nix:

[Scoffs] Oh then it must be true! I don’t know… I mean that’s exactly what I’m talking about. My understanding is that the U.S. Congress is undertaking an investigation into Russian interference into the election and they’ve asked all sorts of people for help into that. That’s not suggesting in any way, any way at all, that Cambridge is under investigation. And you know we’re more than happy to help. We never worked in Russia. We never worked for Russia. I want to be careful, but I don’t think we have any Russian employees in our company whatsoever. We just don’t have business in Russia. We have no involvement with Russia, never have done.

MB:

What about for third parties associated with Putin’s government?

Nix:

I wouldn’t even know who they were and where to begin. I mean, we worked directly for the campaign, as indirectly, and we worked for a Super Pac in support of the campaign [called] “defeat crooked Hillary” was it’s unofficial title or “keep the promise” or something.

MB:

You have an investor, Robert Mercer. What sort of independence does that give you? He has known political views. Do you feel independent of an investor like that?

Nix:

Well, actually, I’m not going to speak about any of our investors or board members at all because we don’t. But I can answer your question which is ‘is our political ideology influenced by other people in the company’ at whatever level? And the answer to that [is this]… We undertake 7 to 9 elections a year, somewhere in the world, for Prime Minister or President. And for as many of those are on the Left of Centre or the Right of Centre. In fact, if you were to total them up, I would probably say – and this is based on a guesstimate – that we’d done more Left-leaning than Right-leaning. Now, clearly in America…

MB:

Can you give me any examples of those Left-leaning campaigns?

Nix:

You’d have to go on our website. I’m sure you could find 25, and you can just see which parties. It’ll all be there. But in America you have to pick a side. You can’t flip-flop. You are not encouraged work for the Democrats in one cycle and then move to the Republicans [on the next]. And the reason the Republicans were attractive to us was because the Democrats were significantly leading the tech arms race. Under Obama through Civas and Blue Labs they had pioneered the use of big data. They were using very sophisticated digital technologies. And the Republicans had been left behind. By the time Romney lost in 2012 there was a vacuum. There just wasn’t the tech talent on the Right to be able to compete. It was like taking a knife to a gunfight. And so that was the commercial opportunity. Now, the reason for that is because most of the tech community, and I’m going to generalize here, but a lot of the tech community that were politically oriented tended to lean Left. People in Berkeley and MIT, and so forth, would, if they were politically motivated, support Hillary or Obama. Whereas, people who might be more Right of centre, obviously, would look typically to go and work in banking or investment management with those skills. And so because of the dearth of talent the Republicans were getting murdered in the tech arms race. That was the commercial opportunity, that was the one we sought to address. Right? Had it been the other way around it might have been a different story.

MB:

What are your own personal political views? Do you talk about those?

Nix:

We leave our personal ideologies at the door. We think that being “foreign” and objective is an asset in elections. I think that a lot of political campaigns, and in the U.S., a lot of campaign staff and vendors get blinded by their own ideology. They blindly believe in their candidate to an extent that they actually can’t see objectively what’s happening in the campaign. They can only see what they and all their friends believe and therefore they assume that’s representative of 200 million voters take

MB:

[You’re saying] They project themselves onto campaigns?

Nix:

Yeah naturally. And there’s something wonderful about coming into a foreign country as an outsider and looking with completely fresh eyes at a political landscape and be able to not have a clouded judgment. And that’s what we bring. And equally, it’s like a good lawyer representing his or her client. You can’t go in there with a preconception of guilty or not. You have to go in there and look at the facts. And that’s what we try to do.

MB:

Do you have a blacklist of anyone you wouldn’t work for?

Nix:

Oh yes for sure. We only work for mainstream political parties. Tories, Labour, Republicans, Democrats. We steer clear of fringe political parties or minority groups. We’re not trying to orchestrate a revolution. We’re trying to provide the best tech… communication technology to political parties. As I said before, elections are about 20 percent of our revenue as a company. We’ve got about 20/25 percent in defence and homeland security. The rest is in the brand and commercial space. We are not a political company. We’re a tech company, and we see ourselves as tech company. We have a tech culture, where we attract academics. You know a third of our staff are PhDs. We’re geeks! Fundamentally, we’re a bunch of geeky people who are trying to solve problems and I would say that politics is probably the least desirable division in the company, because it can be divisive and people don’t necessarily like to get involved. But, if you give a data scientist a really challenging problem like identifying the ideology of a nation or an issue, a model or something, it’s about solving the problem. It is not about trying to promote their own personal ideology or agenda or anything like that.

MB:

You’re working with Palantir?

Nix:

No. Palantir was established about nine or 10 years ago now. They’re very active of course in the defence, homeland security. They were a pioneer and a leader in this field. Peter Thiel, in applying both his platforms, Gotham and Metropolis, and other work which is slightly more off the radar, it is truly revolutionary. I mean these guys were genuine first movers. And I think that companies like us have caught up. But kudos to them. They were really very early on to the scene.

MB:

I think you count the Pentagon as a client don’t you?

Nix:

We formed a defence/government defence division in 2005. Over that period we’ve worked for global militaries all over the world. We train a lot of armies in something called PSYOP, which is psychological operations or information operations, which is, sort of communication warfare. It’s trying to understand how to persuade troops not to fight or to persuade your troops to fight. It’s trying to combat hostile behavior or how do you counter radicalization or counter-terrorism, and so forth. We do a lot of information operation programs ourselves [where] we go into countries and conduct the research and the campaigns to change behavior to reduce conflict. And our clients do include, in the U.K, the MOD and the FCO, and in the United States, all the ‘coms’, so NorthCom, Safcom, State Department, Pentagon and various ‘three letter agencies’ and so forth.

MB:

What’s your what’s your vision for the future? You’ve talked about psychographic profiling, analytics about the amount of data sets there are, and the data you can pull out social media. And of course, we all know that Alexa’s in their houses recording what they are saying. Where do you see things heading? Firstly, which direction do you feel your own company is going in, given the amount of data out there? Secondly, do you think you might end up butting up against the Google and Amazons in data collection?

Nix:

There are several questions there. Let’s start with the bigger picture. There are two technologies that I’m really excited by and that everyone is talking about. Clearly, IOT is going to totally radicalize the data market. I think the data business is doomed, myself. It’s a very, very high volume and very low margin [business]. As the internet of things grows, as we have sensors on everything: cars, fridges, TVs then data is going to become ubiquitous. Therefore the volume of data will increase, the price of data is going to go down. You won’t be able to sell data in the way you can today. I think people are going to start taking control of their data much more. There is going to be more reciprocity in the way that people share their data with companies like my own and other marketing agencies. But generally, the increase in data is one factor that is going to make analytics companies like ours more valuable. More data is going to need more analytics, period. And then at the other end — if you see it as a sandwich and we’re in the middle — you’ve got blockchain. And by having distributed ledger technology you’re going to an ability to have transparency, and to have accountability as to how data is and data sets are being used and implemented, forevermore, in perpetuity. And so, yes the data landscape is getting more frightening with IOT. But on the other hand, it’s going to be to be more self-regulated through the Blockchain and it’s going to be more transparent. And both of those things are the bread rolls with the analytics being the chess in the middle of the sandwich. Analytics are going to play more and more of a function in deciphering huge quantities of data, making sense of it, applying it into many different areas and then using blockchain technologies to securitize that.

In terms of the advertising industry: Look, I’ve been very vocal about this but I don’t think that, again, I’m sort of some sort of ‘soothsayer’. I think a lot of people in the industry recognize this… And even if they are only whispering to each other… I think the advertising industry is like lemmings on the edge of a cliff. They can’t go backwards and forwards looks terrifying. Omnicom, Dentsu, WPP… they’re trying to pivot. They’re acquiring companies left right and centre. But you can’t just buy a data company and squash it together with an ad agency and hope it’s just going to work. It doesn’t work like that, that it’s a different culture. It takes integration. You need to grow these things together. You’ve got all the consultancies which saw a commercial opportunity in the last two or three years and started acquiring data companies. They’re trying to acquire advertising agencies in order to get into this space. Then nipping at the heels of the big conglomerates and taking considerable market share from them. You’ve got the big brands themselves understanding their data is so valuable they no longer want to give that away to advertising agencies. They can bring some of these capabilities in-house and have their own data analytics and marketing agencies in-house. That’s damaging them.

Then you’ve got the small disruptors like us who are only going to become more numerous. We’re eating a piece of the pie. So, I think there is going to be a reckoning, and it’s happening now. WPP’s market share has taken a nosedive in the last month or three. But they’re not going to be the only ones. It’s going to continue. I’m not suggesting that they’re all going to go bust, but I am saying it’s “adapt or die”. This market is fundamentally shifting and about time too! This is overdue. Gone are the days where an advertiser does an advert. And as long as the client’s wife likes it there are no metrics other than audience recall to quantify its success. Or very few. And they don’t care anymore. They can just squeeze a lemon and get some money out of advertisers. I think that advertisers want more accountability, they want more measurement of effectiveness, they want empirical data to be able to justify these enormous multi-billion dollar spends.

MB:

Let’s fast forward say,10-20 years. There will be people who can afford to buy privacy and then there will be plenty of people who will give away their data in return for services, as they do now. Do we do we think that that’s a good situation to be in? What’s your view?

Nix:

I think gone are the days where people just click a box without really thinking it through, and all their data has just been siphoned away and gone. Grabbed. I think people are recognizing that data is valuable AND that they’re [also] saying, “Well actually it’s not that sensitive. I don’t really care much if people understand my shopping habits or what car I drive. This isn’t health or financial data. But it is valuable and why should I just give it away so that other firms and advertisers can make money out of it?” So I see more of a reciprocity. I see people having something like a virtual data wallet. They’re going to have control of their data. You’ll be able to say to them “Hey can I licence your data or use your data for a certain campaign or purpose?” And there’s going to be an exchange there. They’re going to say “Yes you can but it’s going to cost you 10 percent off that” or “I want this in return.” And I see that market emerging as people take control. I think that’s really sensible. I think it gives people more control and therefore it gives them more protection. I think advertisers will need to be a little more targeted in the way that they use data and they gather data, which is probably good. But actually, it’s not going to dent the industry or the direction that it’s growing in. So I really hope that people like the ICO [Information Commissioner’s Office in the UK which rules on data privacy for individuals], who are suddenly trying to catch up on the last five years of data. I hope that they understand that the regulation needs to be there to protect consumers, but not to stump the growth of an industry that could really do a lot of good. Not just in communications, [but] across all corporate sectors.

MB:

If consumers had more control over their data wouldn’t that start to slightly stump the work that you do?

Nix:

No, I don’t think it will because I think things are changing. I think that the older generation, our parents or even older… you know, this is a terrifying brave new world for them. “What do you mean someone knows what car I drive?!” “Yes, mother they do know what car you drive” “But that’s awful!” “Why is it awful?” “Well because I didn’t want them to know that!” “Do you care?” “That’s not the point.” “Well, it is the point!” Actually, the new generation, the next generation, younger than us, they don’t care. They actually just don’t care.

MB:

They are used to this world?

Nix:

They are used to this world and they realize it. “Do I care if people know what car I drive, what cereal I eat for breakfast?” And why should they, really? They don’t care if they put a picture of themselves blind drunk on Facebook doing something. They don’t care. Let alone [someone knowing] what car they drive.

MB:

Do they care if they feel that it might influence an election?

Nix:

Well, that’s a good question. Ultimately, I don’t think people are naive, now, especially not the Internet generation, the Millennials. I think they do understand what’s going on. There’s been so much press. It’s not about hoodwinking people. Remember, it’s the same for all sides. It’s not like Trump had some secret sauce that he was employing with Cambridge that the Democrats didn’t. Hillary’s data and digital teams were up to 200 people or something! Huge! Huge! This was tried and tested. It was a machine! They were doing everything! But the reason they’re not in the spotlight is twofold. A: Hillary lost. And B: Trump’s, you know, is somewhat perceived by many as more of a polarizing character. That’s why. It’s not what we did. I mean, I think if we’d done exactly the same work, no different, but done it for Hillary…

MB:

You think the result would have been the same?

Nix:

No, I think no one would care. The Guardian wouldn’t be writing these stupid headlines and nor would The New York Times. They wouldn’t care. This is not about Cambridge. It’s not about our tech. It’s about Trump.

Facebook Is Shutting Down Its API For Giving Your Friends’ Data To Apps

It was always kind of shady that Facebook let you volunteer your friends’ status updates, check-ins, location, interests and more to third-party apps. While this let developers build powerful, personalized products, the privacy concerns led Facebook to announce at F8 2014 that it would shut down the Friends data API in a year. Now that time has come, with the forced migration to Graph API v2.0 leading to the friends’ data API shutting down, and a few other changes happening on April 30.

Today Facebook assembled journalists in San Francisco to discuss the rhetoric behind the change. All apps created since April 20, 2014, already have the new systems, so you’ve probably seen them in the wild. But all new developers must comply with updated APIs, or their connection to Facebook will stop working.

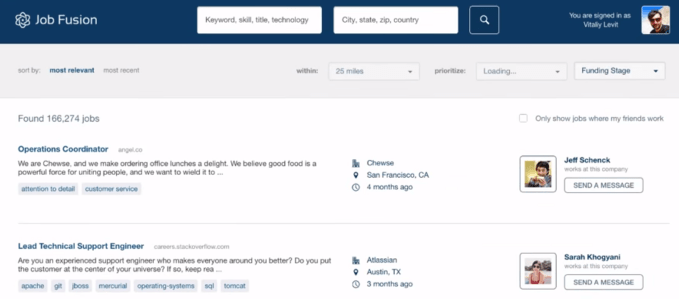

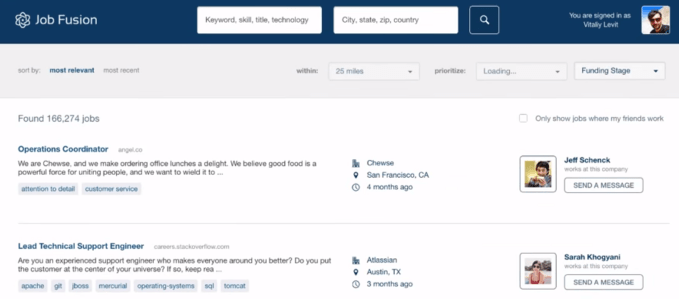

Job Fusion will have to shut down its referral engine

Some users will see it as a positive move that returns control of personal data to its rightful owners. Just because you’re friends with someone, doesn’t mean you necessarily trust their judgment about what developers are safe to deal with. Now, each user will control their own data destiny.

Along with the year notice, Facebook reviewed 5,000 of the top apps and sent them feedback about how their app will perform after the change. Its goal has been to minimize the impact on users.

Facebook’s Simon Cross told reporters that Mark Zuckerberg said one of Facebook’s new slogans is ‘People First’, because “if people don’t feel comfortable using Facebook and specifically logging in Facebook and using Facebook in apps, we don’t have a platform, we don’t have developers.”

To inform its new policies, Facebook did extensive in-person research, asking users how they felt about their privacy when they used Facebook with apps. It came away believing that to ensure the long-term health of the ecosystem, it has to give users confidence in how their app privacy is handled. When people are confident, “they feel happier and use our stuff more, and that’s what we’re tying to achieve” says Cross.

On the other hand, some developers will have significantly change how their apps work, or turn them off altogether. For example, Job Fusion relied on the ability to pull where a user’s friends work to show them job openings at those companies. Now Job Fusion is shutting down its referral engine, though it will continue operating in different ways. Others going dark or that already have due to the change include CareerSonar, Jobs With Friends, and adzuna Connect.

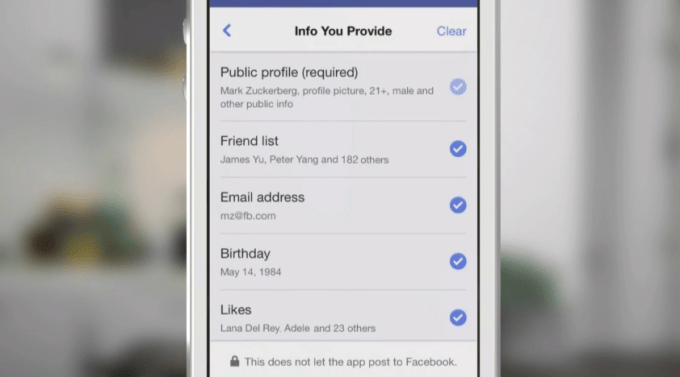

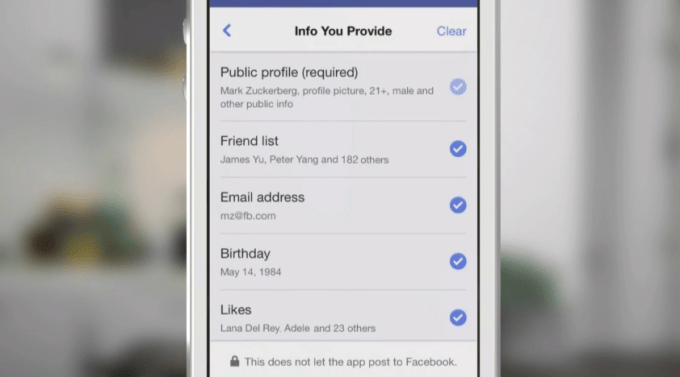

Along with the friends data API change, Facebook is now requiring all apps to use its new login system, which gives users more granular control over what data they give developers. Previously, users provided all their data and permissions in two big screens. One for all personal info and one for the ability for an app to post to Facebook on your behalf.

Now on the log-in screen, developers must include an “Edit the info you provide” link, which opens a checklist of all the data and permissions they’re asking for, including friend list, Likes, email address, and the ability to post to the News Feed. Users can tap the checkmarks to deny certain permissions.

Lastly, Facebook has now instituted Login Review, where a team of its employees audit any app that requires more than the basic data of someone’s public profile, list of friends, and email address. The Login Review team has now checked over 40,000 apps, and from the experience, created new, more specific permissions so developers don’t have to ask for more than they need. Facebook revealed that apps now ask an average of 50 percent fewer permissions than before.

So what does April 30 mean for users? In some cases, nothing. Apps that don’t need extra permissions and that function if they’re missing some like your email address will automatically get the new login systems and will work normally, and users won’t have to log back in. If a developer is significantly changing an app or needs more permissions, users may need to log back in, or the app might perform weirdly or show roadblock error messages. And some apps may simply cease to exist.

Apps don’t have to delete data they’ve already pulled. If someone gave your data to an app, it could go on using it. However, if you request that a developer delete your data, it has to. However, how you submit those requests could be through a form, via email, or in other ways that vary app to app. You can also always go to your App Privacy Settings and remove permissions for an app to pull more data about you in the future.

Overall, the changes could boost confidence in Facebook’s platform and the social network itself, which has struggled in the past with a reputation for spotty privacy. Cross says the conversion rate on people logging in with Facebook has increased 11 percent and believes this means “More people feel comfortable logging in with Facebook.”

Facebook’s never been shy about prioritizing users over developers and advertisers. It’s repeatedly reduced app virality to protect users’ feeds from spam, and denied advertiser requests for more flashy, site takeover-style ads. Facebook knows that if it burns users now, usage will wither, and all developers will get hurt.

And while developers might not like the changes, Facebook tried to give them as much warning as possible.