At a conference in New Delhi early last year, Netflix CEO Reed Hastings was confronted with a question that his company has been asked many times over the years. Would he consider lowering the subscription cost in India?

It’s a tactic that most Silicon Valley companies have adapted to in the country over the years. Uber rides aren’t as costly in India as they are elsewhere. Spotify and Apple Music cost less than $2 per month to users in the country. YouTube Premium as well as subscriptions to U.S. news outlets such as WSJ and New York Times are also priced significantly lower compared to the prices they charge in their home turf.

Hastings had also come prepared: He acknowledged that the entertainment viewing industry in India is very different from other parts of the world. To be sure, much of the pay-TV in India is supported by ads and the access fee remains too low ($5). But that was not going to change how Netflix likes to roll, he said.

“We want to be sensitive to great stories and to fund those great stories by investing in local content,” he said. “So yes, our strategy is to build up the local content — and of course we have got the global content — and try to uplevel the industry,” he said, identifying movie-goers who spend about Rs 500 ($7.25) or more on tickets each month as Netflix’s potential customers.

Indian commuters walking below a poster of “Sacred Games”, an original show produced by Netflix (Image: INDRANIL MUKHERJEE/AFP/Getty Images)

Less than a year and a half later, Netflix has had a change of heart. The company today rolled out a lower-priced subscription plan in India, a first for the company. The monthly plan, which restricts usage of the service to mobile devices only, is priced at Rs 199 ($2.8) — a third of the least expensive plan in the U.S.

At a press conference in New Delhi today, Netflix executives said that the lower-priced subscription tier is aimed at expanding the reach of its service in the country. “We want to really broaden the audience for Netflix, want to make it more accessible, and we knew just how mobile-centric India has been,” said Ajay Arora, Director of Product Innovation at Netflix.

The move comes at a time when Netflix has raised its subscription prices in the U.S. by up to 18% and in the UK by up to 20%.

Netflix’s strategy shift in India illustrates a bigger challenge that Silicon Valley companies have been facing in the country for years. If you want to succeed in the country, either make most of your revenue from ads, or heavily subsidize your costs.

But whether finding users in India is a success is also debatable.

The great growth market

As growth of Silicon Valley companies slows in developed markets, and China keeps its door closed for them, India has emerged as their last great growth market. At a time when much of the world has come online and smartphone sales are either plateauing or dropping, India has reported strong growth on both counts for several years.

And much of the country remains untapped: India, home to more than 1.3 billion people, has about 350 million smartphone users and over 500 million internet users. Moreover, many experts caution that these figures do not necessarily represent unique users. So the country might be even more underserved.

Google’s former Vice-president for South East Asia and India, Rajan Anandan, briefs about the new TEZ app. (Photo by Sonu Mehta/Hindustan Times via Getty Images)

For three of the Big Five (Amazon, Google, Facebook, Microsoft, and Apple), India is either their fastest growing market or the biggest (by number of users) — or in some cases, both. YouTube, which has more than 270 million users in India, is growing faster than its parent company in the nation, company executives said at a marketing event last year.

Facebook and its instant messaging service WhatsApp reach more than 350 million users in India, the company has told marketing agencies privately. More than 98% of smartphones that shipped in India last year ran Android mobile operating system, according to research firm Counterpoint.

Kunal Shah, cofounder of fintech startup Cred, who sold his payments firm Freecharge to e-commerce firm Snapdeal, believes India has become “the MAU farm” for global technology companies. At a conference earlier this year, he said companies love to come to India because they can quickly expand their global user base figure for little cost.

So it did not come as a surprise when Netflix announced it was changing its strategy for India, too. “Netflix could address a sizeable target market in India. One could draw parallels from the Indian multiplex industry, which caters to 100 million consumers spending an average US$4 per movie. However, Netflix will need to strike the right balance of ensuring a steady supply of original local content,” said Mihir Shah, Vice President of research firm Media Partners Asia.

It’s a tried and tested tactic that has proven immensely beneficial for other streaming services in India. Hotstar, which is owned by Disney, offers about 80% of its content catalog to users at no charge.

It instead generates revenue off of advertising. Even its premium option, that features titles from networks and studios such as HBO and Showtime and strips off ads, costs less than $14.5 per year. It has amassed more than 300 million internet users.

Video streaming services in India are expected to generate about $1.2 billion in revenue this year, according to Media Partners Asia. Ad-supported services would bring in 810 million of that, according to the firm.

The other problem

But just adapting to local conditions in India is not going to be enough for Netflix — or anyone else. Over the past year, it has become increasingly apparent that for now, India is not going to contribute much to the bottom line of any company — despite their reach in the country.

Hotstar is not profitable, people familiar with the matter told TechCrunch. Neither is Gaana, a music streaming service with more than 100 million users that charges less than $6 a year for its premium offering.

In an interview with TechCrunch in May, Satyan Gajwani, Vice Chairman of Times Internet, a conglomerate in India that claims to reach more than 450 million internet users in the country, admitted that ads alone are no longer enough to break even.

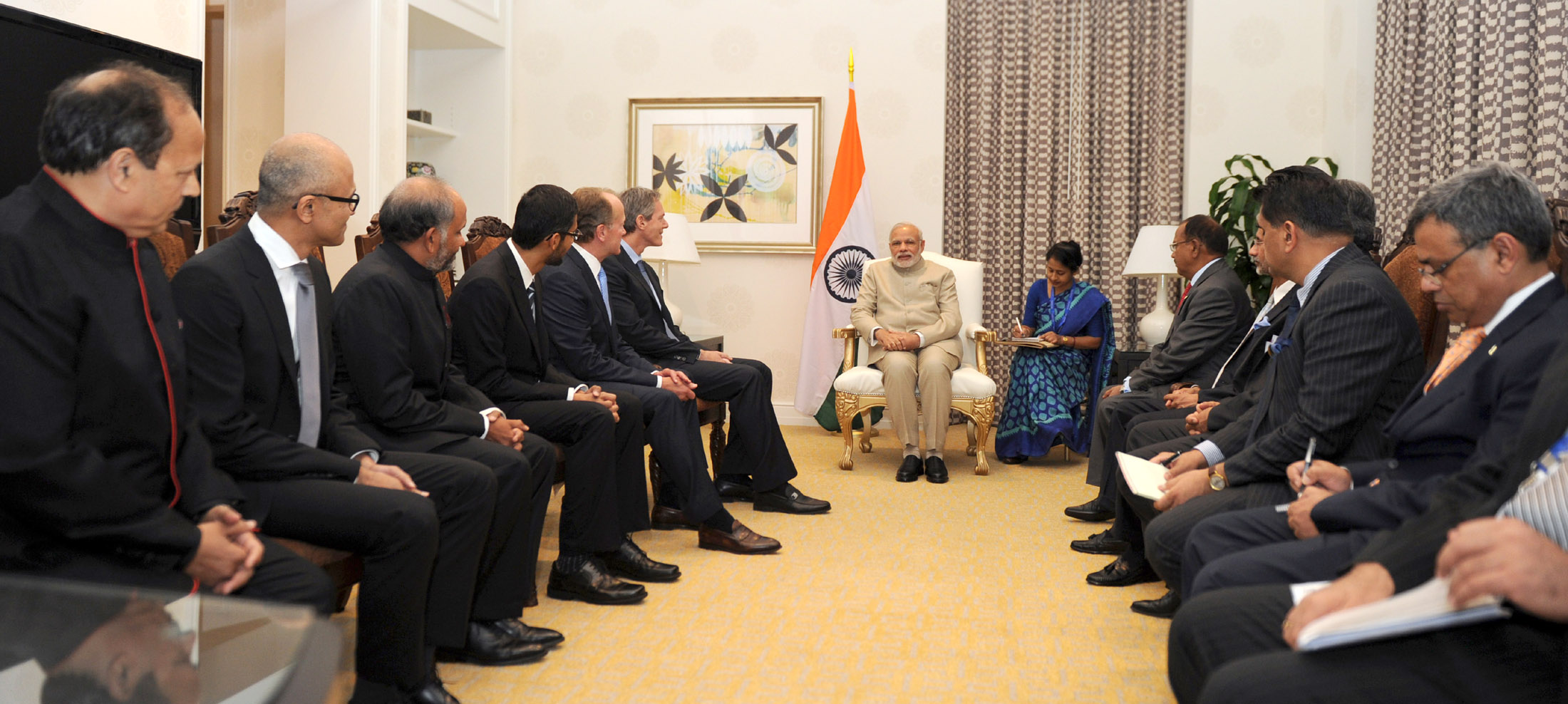

India’s Prime Minister Narendra Modi with chief executives of several Silicon Valley companies in 2015. (Image: Press Bureau of India)

In a recent interview with TechCrunch, Rajan Anandan, former head of Google India and Southeast Asia, said ads alone are unlikely to fully support a small or mid-sized business in India, unless they have found a niche audience. Vijay Shekhar Sharma, founder and CEO of financial services firm Paytm, also discounted ads as a viable business for emerging companies.

Even for Silicon Valley companies, India’s contribution to their bottom line is a blip at best. Google generated $1.4 billion in revenue in India in the year that ended in March 2018, compared to the $110.9 billion it generated globally.

Facebook generated $78 million in India revenue, compared to the $39.9 billion it reported globally during this period. Amazon’s revenue in India, where it has invested more than $6 billion to date, stood at $754.2 million, compared to $177 billion globally.

Netflix, Facebook, Google, and other global companies are increasingly betting that they need to succeed in India. But there is little evidence currently that this bet is going to make a difference to their financial performance any time soon — assuming that it would, someday.

Until then, the India push is very likely to continue, if not witness some acceleration. A partner at a prominent VC fund, who requested anonymity, told TechCrunch recently that increasingly startups in the U.S. are bringing India in their presentations when they wish to raise money. How this would help them is a question that very few are able to answer, the person said.

And this bet is coming at a time when the Indian government, once very welcoming of foreign investment in the nation, has proposed or enforced several “protectionist” regulatory changes in last year and a half that are already hurting foreign companies.

In the meantime, an argument could be made that by lowering the price in one country, companies are risking diluting their brand value everywhere. Like Hastings, when Apple CEO Tim Cook visited India in 2016, he was asked if he would consider launching cheaper iPhone models in India or lowering the prices of its existing lineup heavily in the country.

Cook danced around the question for minutes and essentially answered no. Very few companies operate like Apple in India. Netflix is no longer on that list.