Almost exactly 10 years ago, I was at GDC participating in a demo of a service I didn’t think could exist: OnLive. The company had promised high-definition, low-latency streaming of games at a time when real broadband was uncommon, mobile gaming was still defined by Bejeweled (though Angry Birds was about to change that), and Netflix was still mainly in the DVD-shipping business.

Although the demo went well, the failure of OnLive and its immediate successors to gain any kind of traction or launch beyond a few select markets indicated that while it may be in the future of gaming, streaming wasn’t in its present.

Well, now it’s the future. Bandwidth is plentiful, speeds are rising, games are shifting from things you buy to services you subscribe to, and millions prefer to pay a flat fee per month rather than worry about buying individual movies, shows, tracks, or even cheeses.

Consequently, as of this week — specifically as of Google’s announcement of Stadia on Tuesday — we see practically every major tech and gaming company attempting to do the same thing. Like the beginning of a chess game, the board is set or nearly so, and each company brings a different set of competencies and potential moves to the approaching fight. Each faces different challenges as well, though they share a few as a set.

Google and Amazon bring cloud-native infrastructure and familiarity online, but is that enough to compete with the gaming know-how of Microsoft, with its own cloud clout, or Sony, which made strategic streaming acquisitions and has a service up and running already? What of the third parties like Nvidia and Valve, publishers and storefronts that may leverage consumer trust and existing games libraries to jump start a rival? It’s a wide-open field, all right.

Before we examine them, however, it is perhaps worthwhile to entertain a brief introduction to the gaming space as it stands today and the trends that have brought it to this point.

Disc to Download

The first major trend has been a sort of corollary to the retail apocalypse that’s taken place over the last two decades. Valve’s Steam was among the first online platforms to seriously contend with boxed software, and the convenience factor associated with being able to buy, download, and manage your games all in one place awarded it the position of dominance in which it is still to be found today.

Gamers first had to overcome compunctions associated with allowing a single company to be lord and master over something that hitherto had none. If Valve went out of business, where would your games go? No one knew. And while Valve is alive and well today, the fear was justified and other services have taken purchases with them. So while this worry has been alleviated, it has by no means been eliminated.

It’s worth mentioning that on the PC especially Steam’s dominance is being challenged by stores touting some major differentiating factor: Fortnite in the Epic Games Store, DLC-free and retro games on Good Old Games, charity and subscription in Humble, and so on. These are interesting but not quite as relevant to our discussion.

Own to Access

An inherited trait of the old diskettes-in-a-box system was that when you bought a game, that was it. It was like buying a book. But the advent of free-to-play (commonly called F2P) games monetized by paid purchases of new characters, levels, or aesthetics demonstrated that other models could indeed be successful. The proliferation of mobile games loaded with in-app purchases was both cause and effect here. This process deserves articles of its own but suffice it to say that it has sufficiently broken the gaming industry out of the box, so to speak, of assuming you literally have to sell someone a game.

This has produced a sort of tripartite structure to gaming at large. Traditionally paid-for games are still common, but more so for independent developers and publishers interested in shipping one-off titles, not platforms. F2P or freemium games have working models established by the likes of League of Legends and Team Fortress 2, now sharpened to a fine point by Fortnite and Apex Legends. AAA games — your Calls of Duty, your Assassin’s Creeds — gnaw players from all sides, commanding an initial $60 investment and then a variety of add-ons in the form of DLC, microtransactions, and monthly subscriptions.

Private to public

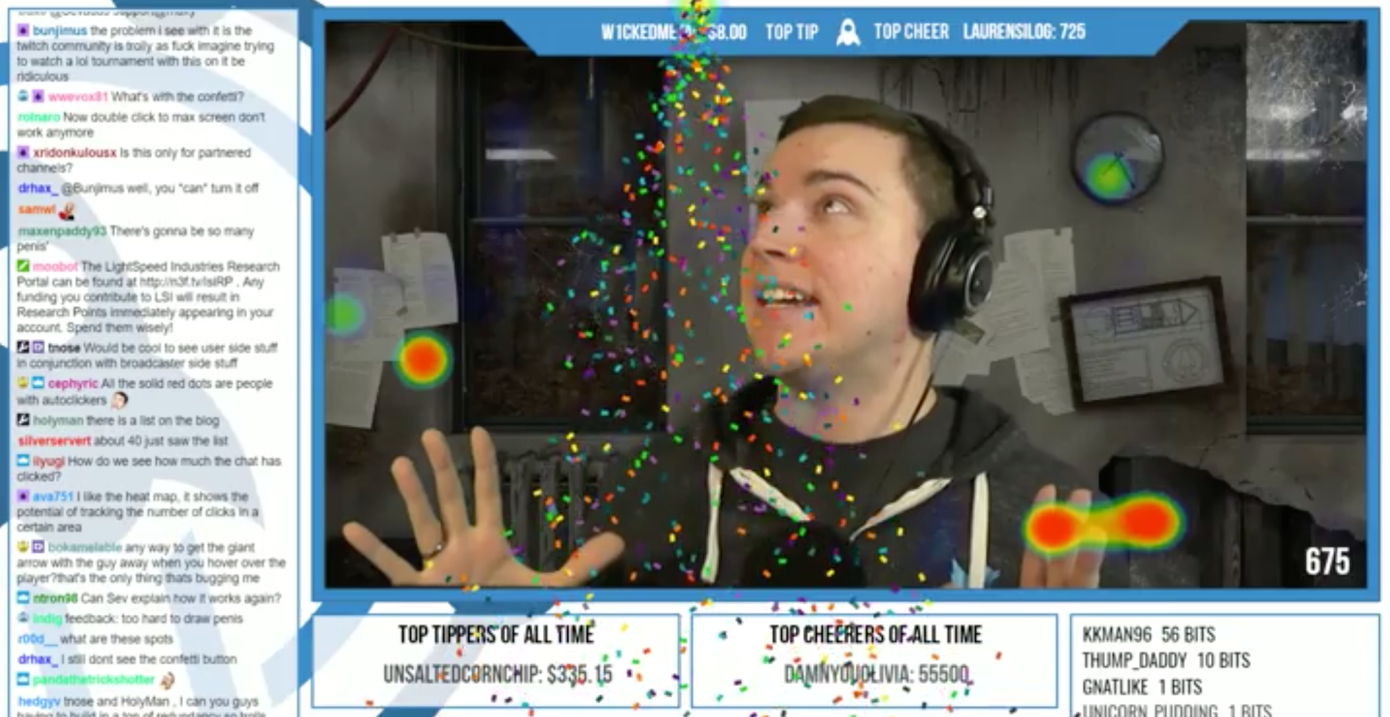

It’s hard to assign credit in the case of who most enabled gaming’s shift from asocial to social, but for our purposes Twitch is the most influential and co-responsible for other relevant changes. It took a trend built by niche services and channels and made it one of the largest media properties in the world. You don’t have to understand why someone would watch someone else play Minecraft rather than play themselves. You just have to accept that millions are doing it for untold hours and growing a whole new global economy in the process.

In addition to the mainstreaming of gaming content consumption, gaming itself has continually emerged from its stigmatic shell and changed from a private hobby to a public one. Here due credit must be given to Nintendo, which has tirelessly promoted public gaming with portable systems, social features, and family-friendly titles. Somehow it feels like smartphone gaming is still in its own silo, of which perhaps we will speak later.

The pieces on the board

These trends all point in a general direction, and as always it is up to those with the power to do so to anticipate this in specific enough fashion to build a business that’s ready before the customers are. Valve did it — Twitch did it — everyone wants to be the next one that did it.

And as often happens in the tech world, everyone is acting as if the starting shot was just fired, when in fact smaller and more innovative companies have for years been doing, or at least attempting, the amazing new things everyone listed will portray as an invention of their own. As usual, the path to success runs through a graveyard.

Let’s begin with the latest and most salient of the companies chasing this particular dragon: Google.

Let’s begin with the latest and most salient of the companies chasing this particular dragon: Google.

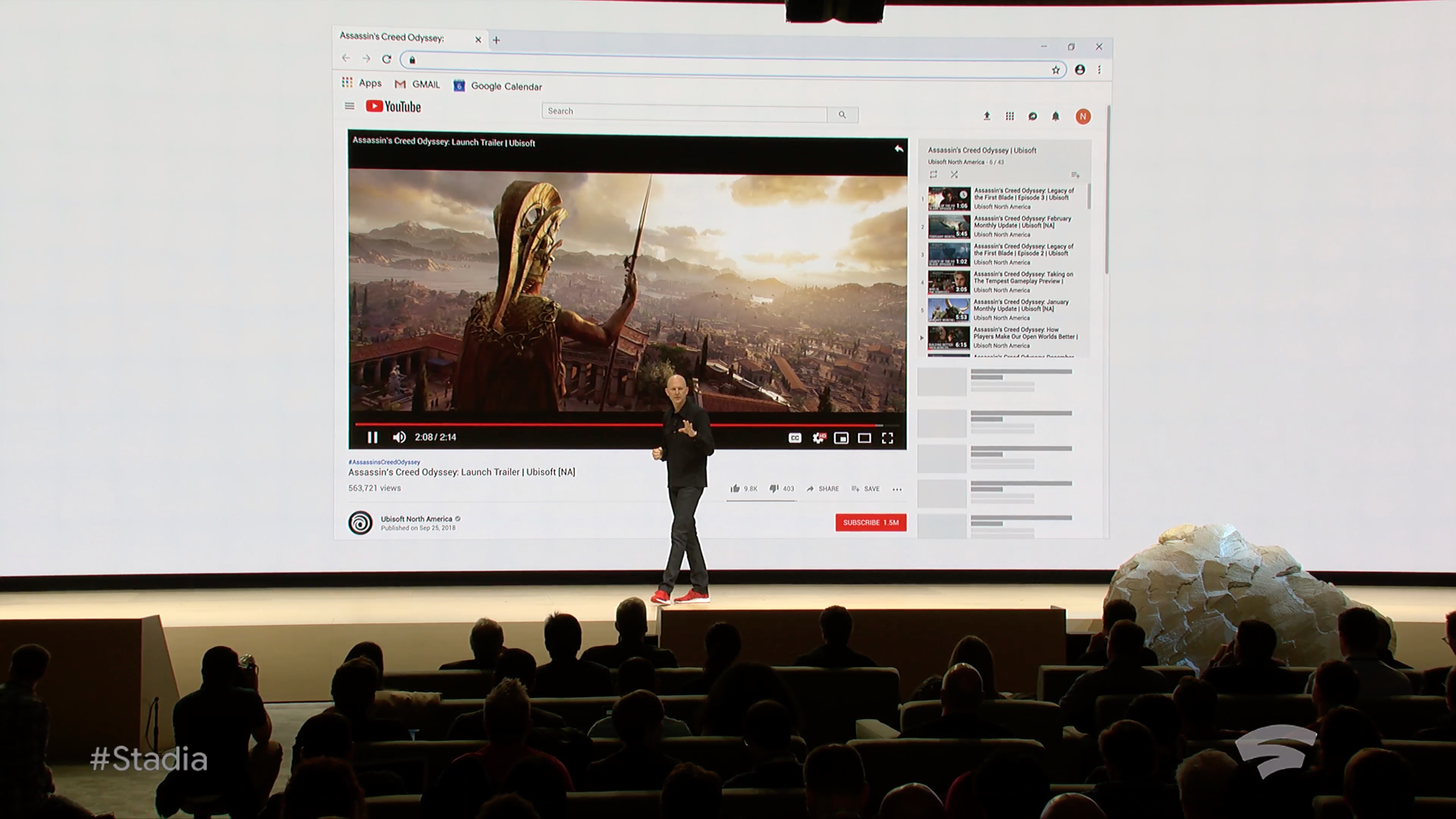

Google’s Stadia was announced earlier this week in a worrying combination of hard specs and big partners, with copious hand-waving in place of minor details like a business model, actual titles, launch dates, and so on.

What Google wanted to show us all was that it has solved the technical issues of delivering streaming games, which is great but very, very far from delivering a working service. Its solution isn’t so different from anyone else’s, except that the company has the positional advantage of having data centers all over the place that are actively and continuously providing high definition content on short notice and low latency to millions worldwide.

Changing that infrastructure to provide a game streaming service is not trivial, but as with others on this list — Amazon and Microsoft in particular — it’s a hell of a lot easier than starting from scratch or adapting a much different base like those of Steam or Nvidia.

While some discussion has been spent on how Google will deliver the necessary 1080p/60 framerate and reduce latency to manageable levels, that’s a bit of a red herring. That Google can do it is to me not in question at all; Whether it can make any kind of inroads into an industry that it has no reputation or competency in is a serious one.

Google has very little history in gaming other than as a gatekeeper to the immense Android ecosystem. No one associates Google with gaming, and there’s no reason anyone should think that it has any real clue what is important to gamers. That is, of course, why it has established an entirely new branch headed by Jade Raymond — but she can only lend the company so much credibility.

In addition to showing gamers that it knows the first thing about providing a gaming service that’s truly for everyone — something actual game companies have been iterating on for decades — Google will have to somehow make them believe that Stadia is not yet another hobby that it will abandon in a couple years.

In addition to showing gamers that it knows the first thing about providing a gaming service that’s truly for everyone — something actual game companies have been iterating on for decades — Google will have to somehow make them believe that Stadia is not yet another hobby that it will abandon in a couple years.

This is not a consideration to be taken lightly, and while it will not harm the use case of, for instance, going from a trailer to playing the game in seconds, it will give any informed gamer pause when asked to pay or otherwise commit. And those few people who already pay for YouTube’s premium service will almost certainly be given a free pass, but these two populations may or may not overlap at all.

Lastly, while many people trust Google to handle private things, the proportion of Google users who actually have or want to give money directly to Google is very, very small. While there are plenty of ways (as the company has shown) to monetize users without taking down their credit card numbers, it does limit the possibilities of Stadia and it would introduce friction to what is meant to be a frictionless system should it decide to charge directly. If Stadia ends up just being another venue on which to show ads, gamers will pick up and move on.

That Google launched Stadia so early and with so little in the way of real details suggests they are hoping to gain a first-mover advantage and establish in advance standards of quality and convenience that others can’t easily match. But these are not the only considerations.

Amazon and Twitch come from a similar position of strength, but without Google’s disadvantages on the gaming and trust sides.

Amazon too operates an immense network of servers, and while AWS is used for many and sundry purposes, it’s not as laser-focused on video delivery as YouTube. But that’s only if you consider Twitch as a separate entity, which at this point there is no need to do. Twitch is really the YouTube for gaming, Google’s aspirations to that title notwithstanding.

Twitch checks the same boxes as YouTube on technical terms, and although we may argue over who has more reach or better presence in this or that region, it would be very difficult to find a way in which Twitch is in any serious way inferior to YouTube when it comes to gaming content.

Twitch checks the same boxes as YouTube on technical terms, and although we may argue over who has more reach or better presence in this or that region, it would be very difficult to find a way in which Twitch is in any serious way inferior to YouTube when it comes to gaming content.

The company and the service already cater to gamers and streamers in numerous ways that indicate a real understanding of what both demographics want and need. People already strongly associate Twitch with live gaming and it feels like a much more natural step for it to become a gaming platform in itself. In addition to this, gamers and non-gamers alike are more than a little familiar with handing Amazon money.

What’s more, the set of users giving Twitch and Amazon money and the set of users who would pay to access games instantly are likely highly coincident. Twitch users are highly engaged and often already financially committed. And there are millions of them. This is far more promising soil in which to plant the seeds of streaming games.

And this is all without reckoning for Prime, as well, which may turn out to be the only real factor necessary to make this all work for Amazon. Anywhere you can see Prime content, you can play any game you own or any game currently on promotion. How does that sound? For many that may be the only factor worth considering, since they’re already paying for it.

(As I was writing this piece, it was reported that Walmart is looking into game streaming as well. Considering how unprepared it is to offer such a service, I think we can ignore its ambitions for now. My guess would be it is evaluating how best to foil Amazon’s inevitable service, perhaps by partnering with or white-labeling a rival.)

Google and Amazon offer two different sides of the “gaming-adjacent service provider” contingent of game streaming ambitions. Neither is a gaming company per se, yet the direction gaming is going seems to involve both of them in some fashion or another. It’s their prerogative to emphasize and expand their role as much as possible, protecting what they see as their space from encroachment by gaming companies looking to take over.

As for those gaming companies: Microsoft and Sony have been arch-rivals in gaming for a long, long time, but the prospect of game streaming opened up a new front in which they are united against FAANG invaders. It’s not quite that simple, of course, but it is fun to think of it this way.

Like Amazon and Google, Microsoft has the advantage of a widespread existing infrastructure in Azure, though it’s difficult to compare it directly to the sheer user-facing real-time brawn and presence of AWS and YouTube. And Sony has already invested heavily in the field, having taken the very prescient steps of buying both OnLive and Gaikai and using them to build its PlayStation Now service.

Microsoft is on record that it will “go big” at E3, with gaming head Phil Spencer sending a rousing email to his division that was promptly (and likely deliberately) leaked. Google’s announcement, he wrote, “is validation of the path we embarked on two years ago.” What does that mean, exactly? Let’s look back a bit.

In 2016 a company called Beam took the stage at the TechCrunch Disrupt Startup Battlefield in New York. It envisioned an evolution of streaming in which players could directly interact with the streamers, suggesting actions, spawning enemies or power-ups, or perhaps even joining in directly. This was very forward thinking, so much so that Microsoft bought Beam just a few months afterwards, later rebranding it (for some reason) as Mixer.

In 2016 a company called Beam took the stage at the TechCrunch Disrupt Startup Battlefield in New York. It envisioned an evolution of streaming in which players could directly interact with the streamers, suggesting actions, spawning enemies or power-ups, or perhaps even joining in directly. This was very forward thinking, so much so that Microsoft bought Beam just a few months afterwards, later rebranding it (for some reason) as Mixer.

Beam and the streaming infrastructure became woven in directly with both Windows 10 and Xbox, allowing a seamless streaming experience that, while not as popular as Twitch or YouTube, is at least more cohesive organizationally. From start to finish it’s all Microsoft.

In October, Microsoft announced Project xCloud, an as yet undemonstrated game streaming service perhaps not yet truly ready for publicity, but which nevertheless served to take a bit of the wind out of Google’s sails. And now, coinciding with rumors last year that Microsoft was preparing to launch a streaming-only Xbox, a “disc-free” Xbox One S is rumored for release around E3. Earlier, in fact, which is a bit strange.

What this amounts to is that Microsoft has been girding its loins for battle going back years: Its service will not be a me-too response but a carefully prepared offering meant to offer serious value to existing Xbox and Windows users (and, naturally, tempt the rest). Don’t underestimate that Windows ecosystem, by the way — it is of course the platform for PC gaming, but it’s also an omnipresent screen, a foil to Google’s Chrome presence, that offers a natural extension of the Xbox brand and service.

What this amounts to is that Microsoft has been girding its loins for battle going back years: Its service will not be a me-too response but a carefully prepared offering meant to offer serious value to existing Xbox and Windows users (and, naturally, tempt the rest). Don’t underestimate that Windows ecosystem, by the way — it is of course the platform for PC gaming, but it’s also an omnipresent screen, a foil to Google’s Chrome presence, that offers a natural extension of the Xbox brand and service.

It’s an interesting position Microsoft is in — in some ways marshaling enormous forces but in other ways lagging behind. Because it would be hard to say that they are ahead of Sony either in console sales or in preparation for the imminent streaming economy.

Sony, as mentioned above, snatched up both OnLive and Gaikai (we wondered at the time if the present cloud push was in progress), and having consumed their DNA has repurposed it into the functional but not super popular PlayStation Now. There’s something to be said for essentially already offering a service that others are only planning on, but the truth is PSNow doesn’t offer the responsivity, fidelity, or selection it should to be competitive with its impending competition. And at $20 per month it isn’t cheap, either.

That said, experience in the market counts for a lot here, and Sony has embraced streaming and video in many ways — perhaps just shooting its shot a bit early. I was tickled to see the Google Stadia controller’s sharing button introduced as if it was some kind of innovation, when Sony included it on the PS4’s controller years ago alongside robust screen and video uploading capabilities. (Let’s be glad other controllers haven’t adopted an “Assistant” button and hope they never do.)

It’s just as bad to launch too early as too late, and unfortunately in this case Sony is at risk of doing both. A competent but inadequate early version showed Sony to be a pioneer but also failed to capture a market; if its competitors show they can do it better and cheaper, the only customers Sony will be able to secure when it does eventually revamp Now will be its existing PlayStation customers. That’s not a good thing when the gaming population is growing; The streaming trend is continually identifying new markets and opportunities, and if all Sony can do is barely hold onto its own, that puts it on the defensive when everyone else is furiously attacking.

It’s just as bad to launch too early as too late, and unfortunately in this case Sony is at risk of doing both. A competent but inadequate early version showed Sony to be a pioneer but also failed to capture a market; if its competitors show they can do it better and cheaper, the only customers Sony will be able to secure when it does eventually revamp Now will be its existing PlayStation customers. That’s not a good thing when the gaming population is growing; The streaming trend is continually identifying new markets and opportunities, and if all Sony can do is barely hold onto its own, that puts it on the defensive when everyone else is furiously attacking.

There are others in the market already, small players like Shadow, GameFly, and Jump. Shadow’s full-VM solution is suited only for PC games and involves considerably more friction than the instantaneous Stadia, but it does what it sets out to do and enables thin clients on small laptops like MacBooks to run the latest titles. The others cater to a specific audience with a limited selection of games.

But these startups may have made the mistake of moving into the neighborhood just before Godzilla and friends arrive. Although they are useful and worth the price for their subscribers, they will find it increasingly hard to compete when major publishers and studios are being courted by the biggest companies in the world. Don’t count them out for acquisition, though.

Nintendo, it may be said, is likely planning something of its own and there’s really no way to tell what the heck they’re going to do. I’d bet on streaming their back catalog, but it could be pretty much anything.

Apple also just announced a subscription gaming plan with few details except that it will be accessible offline, which rules out a streaming play. They were never really a likely contender in this space anyway, despite the fact that being able to stream games on macOS would mitigate decades of scarcity.

The last group of players might be said to be the middlemen: those who occupy a privileged place in the gaming ecosystem and may attempt to use that as a foot in the door in the emerging streaming economy.

Take for example EA. Here is a company that wields immense power and money and also holds the reins to some of gaming’s biggest franchises. In an extremely long blog post (though not as long as this one), EA’s CTO Ken Moss held forth last October on what he called Project Atlas, an attempt to boot up a cloud-native, AI-informed game development and consumption platform.

He puts quite well the uncertainty and great potential of the present period:

He puts quite well the uncertainty and great potential of the present period:

We’re at an inflection point where major, complementary tech disruptors are falling into place. As an industry, we’ve made remarkable technological advancements in AI, cloud, distributed computing, social features, and engines. But because all of these technologies have continued to evolve separately, it’s been difficult to conceptualize what we could achieve by bringing them together.

He then outlines various ways in which cloud-native games could split tasks between local and distant machines, how an evolving game world could reflect the contributions of thousands of players simultaneously, and how AI-assisted development could create richer and even never-ending stories and environments.

It all sounds quite nice, but the truth is everyone hates EA for its all-consuming avarice and willingness to compromise or sink its own games and studios in order to make a buck. The details (and casualties of EA’s management) are a story for another day, but let’s just say that exactly as many gamers will use an EA streaming service as absolutely need to, for instance if the company made Battlefield or Apex Legends exclusive to its platform. Which it probably would.

Epic Games and its new store are in a similar position but attract less antipathy. As the new and flush kid on the block thanks to rich uncle Fortnite, Epic is more focused on establishing a credible library and luring users away from Steam one by one with aggressive exclusivity deals and regular giveaways.

It seems too early in Epic’s current push for it to have considered and built out the kind of streaming infrastructure it would need to compete. Right now it is not worried about invaders taking over a space it has no chance of dominating, but rather chipping away at the market share of a longtime leader that has in some ways grown complacent and arguably too greedy. As the PC market has grown and diversified, and storefronts and distribution methods multiplied, Steam’s once unassailable position has been eroded considerably.

Valve has a better chance of making inroads and in fact has been working on its own streaming services for a long time. The hardware side of things hasn’t really worked out for them, but the captive and largely satisfied user base they have with Steam provides a large and diverse population for testing new products.

In a way Valve may be largely immune to competition in this specific arena because it is far less interested in providing an entirely new cloud-based game playing economy and more about adding value to its existing one. Many, perhaps even most, gamers own games on the Steam platform, and services like Link allow them to play those games on any compatible device. There’s no additional fee, no new account to make, no special hardware (at least, not any more).

The catch is of course that you have to own the game you want to play, and you have to pay full price. Of course we can’t rule out streaming demos, which would be an excellent play for Steam, but that doesn’t really amount to the same thing. That’s essentially a playable advertisement, not a gaming platform.

Nvidia’s GeForce Now is another existing service that, like PlayStation Now, works well in the right circumstances but still remains a niche product. The biggest hurdle with GeForce Now is that you can’t, unlike many other services and of course the promised Stadia, just play with the gear you already have. You’ll need nearly $200 or so for the initial Shield TV setup if you don’t have a compatible tablet already, then $8 a month to access a considerable library of games.

The option of running on a non-Shield PC or Mac is there, but the pricing is strange and expensive. Latency is also a problem if you’re not on a wired connection — that may prove to be true for many of these services, but reviews of GeForce Now have mentioned it in particular.

Obstacles and opportunities

As you can see from the lengthy preceding list, there’s a lot going on in this space.

Companies in the gaming world are lemming-like in the way they follow trends that often come to nothing, such as motion controls (a Nintendo miracle, disastrous for Sony and Microsoft) and VR (with dozens of companies throwing good money after bad to evolve a market that doesn’t exist) and game design ideas (hope you like survival elements!).

So it’s no surprise that as bandwidth and computation resources reached the inflection point of being capable of providing 1080p video at 60FPS, the lot of them decided they’d all run in the same direction. No one wants to be left behind.

So it’s no surprise that as bandwidth and computation resources reached the inflection point of being capable of providing 1080p video at 60FPS, the lot of them decided they’d all run in the same direction. No one wants to be left behind.

But the idea of streaming is not one that will sit well with all gamers. There are serious concerns about how these things will be administrated and paid for.

The obvious one, of what happens to your games when a service disappears, applies to every company here with the partial exception of Valve. This is part of a paradigm shift that has happened in TV and movies but not yet in games: the acceptance of access instead of ownership.

Games that are access-native, like Fortnite and Dota2, don’t worry gamers much. These are more like places you go than things you get. But the latest Assassin’s Creed, with its multiplicity of DLCs and in-game purchases, does worry them. Few people care to have a boxed product any more, but many gamers don’t want service or company stepping in between themselves and the item they’ve purchased. That’s going to be the new norm with streaming. Trust of major tech companies is not exactly at an all time high and these new systems require trust.

Smaller developers and publishers may rightly fear this new economy. Many indie developers only thrive because they can offer a $20 game to a niche audience that pays full price, and that pays salaries for the next year or so. That model ceases to exist with streaming, just as independent musicians struggle to make real money via Pandora and Spotify. The payment structures are biased against small creators, at a time when small creators are valued more than ever; alternative payment structures like Patreon are of course viable but ideally an indie should be able to compete in the mass market just like a AAA title. That’s the dream, anyway.

There are technical and practical considerations as well. Not everyone has the kind of connection or equipment necessary to make this work, and that sort of fundamentally creates a limit to who can access this new ecosystem. Furthermore, streaming a game at 1080p/60 may consume 4-5 gigabytes of bandwidth per hour. Add in Netflix and regular browsing and those terabyte-level bandwidth caps imposed by ISPs start looking a lot smaller. ISPs are unlikely to zero rate such bandwidth-hogging applications, and even if they did, it would be a bad idea.

This is all only to say that victory in the emerging game streaming space will not be assured merely by number of datacenters, or cheapest plan, or biggest game selection. The gaming industry, and gamers, exist independent of the streaming ecosystem and the way they have begun to overlap is still tentative and new. Everyone is excited about new opportunities and ways to play, but those opportunities bring unique challenges as well. It will be exceedingly important to solve for these unique challenges if gamers are to adopt and embrace streaming. If the servers are ready but the ideas aren’t, streaming will be a platform without legs.