Editor’s note: Jon Orlin is the Production Director for TechCrunch TV

This past week, formerly unknown actress Elyse Porterfield fooled millions playing Jenny, the Dry Erase girl, who quit in a clever hoax. Right now, I guarantee other pranksters are dreaming up new schemes to fool you again. And journalists, who at one time were tasked with protecting the public from such lies, no longer have the same power to block them.

This past week, formerly unknown actress Elyse Porterfield fooled millions playing Jenny, the Dry Erase girl, who quit in a clever hoax. Right now, I guarantee other pranksters are dreaming up new schemes to fool you again. And journalists, who at one time were tasked with protecting the public from such lies, no longer have the same power to block them.

The media has reporters and editors in place to prevent hoaxes from going public. Sometimes it works, sometimes it doesn’t.

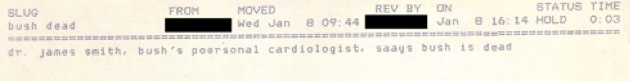

The Jenny story was a fun, harmless, light story. But, hoaxes can involve a story of major global importance. I was in the CNN newsroom in 1992 when our medical reporter got exclusive information that then President Bush had died at a dinner in Japan. The first reaction was shock. Then, the newsroom got very quiet and we struggled to decide what to do. Trust our reporter and break the story or get a second source and risk someone else beating us on the story. If we decided to go with it and we were right, CNN would have become the first to tell the world this huge news and gain credibility. (Dan Rather built a career after being first to report on the Kennedy assassination.) If we reported it and were wrong, we would have spread a huge lie and suffered a major embarrassment.

CNN decided to get confirmation first and soon discovered it was a hoax. But our sister network, Headline News, started to report on the “tragic” news until a wise producer told the anchor to stop.

For the most part, we were able to prevent the hoax from getting out. But, today it might be different. Just one unauthorized tweet from inside CNN could start an unstoppable viral explosion. ABC’s Terry Moran created a stir last year by tweeting about an off-the-record comment where President Obama called Kanye West a jackass in an interview that had not yet been edited for air. Certainly not a story of major importance, but it does suggest that media organizations can’t control their employee’s tweets.

I always hated working on the early morning shift at CNN on April Fool’s day because I knew we’d have to vet some hoaxes at 4 AM. Our credibility would suffer if we presented fake stories to the world. One year, Taco Bell bought ads in major newspapers saying it was buying the Liberty Bell and renaming it the Taco Liberty Bell. We reported on the ads, but that it was also April Fool’s day. AOL ran a headline that life was discovered on Jupiter. That one generated 1,300 messages on AOL (huge for those days) and was considered by some to have risked AOL’s credibility.

There were many other fake stories the public never heard because they were vetted by journalists. And without the media, there was no way for these stories to spread.

That’s all changed. With social media, there are no editors. There is no waiting for confirmation. When you tweet or re-tweet, you are not checking the facts or even so much concerned if you are spreading a lie. When the Dry Erase Girl meme hit the Web, 421,000 users shared the story on Facebook, and theChive got 2.5 million unique visits for two days in a row, the same amount it normally gets in a month.

Jenny’s story, which many people wanted to believe, was posted on theChive at 4:30 AM. The site claimed they got the photos from someone who works with Jenny, but they even admitted Jenny’s name was not confirmed. It was then re-posted at College Humor, and by many others including TechCrunch, on which Jenny had claimed her boss spent 5.3 hours a week reading. Really just bait for us to run the story.

TechCrunch’s first post included a link saying “via The Chive.” It was a water-cooler story about a spreading internet meme with the playful headline — It’s Official: The Best Bosses Read Techcrunch. It was an amusing slideshow, regardless of whether it was true or not.

At the same time, our reporters were trying to contact Jenny. Were there some red flags? Sure, Jenny, if that was her real name, had no last name and the name of her company wasn’t mentioned. But, this is how process journalism now works. It’s journalism as beta.

In the days before social media, I think news organizations might have held the story. Now with the instant viral spread of information that happens even without the media, the story is out there whether we report it or not. The man behind the hoax, theChive’s John Resig told TechCrunch “we didn’t need mainstream media to make this happen, we just needed the people… This was spread through Twitter, Facebook and interoffice emails.” We certainly helped to spread it (and debunk it) faster than it would have on its own. But did TechCrunch and all the other media who published the fake story suffer a loss of credibility? You tell us. But my sense is, not really. We helped move the story towards the truth.

Peter Kafla at All Things Digital was the first to publish some skepticism, saying the story was “almost certainly made up.” TechCrunch was first to confirm the true identify of Jenny that night and followed with a video interview the next day. Yes, we extended Jenny’s 15 minutes of fame and it was also our most popular video of the day. Jenny (oops, I mean Elyse) told us she just taped an interview with Edward R Murrow’s CBS News before our interview. (Before the hoax had been revealed, Good Morning America and Jay Leno wanted to talk to Jenny ASAP.) Even if a news organization didn’t report the initial hoax, many will do the story behind the story and what, if anything, it means. Guilty here too.

So, what’s a reader to do? Enjoy the story and smile at the clever hoax? Get angry and don’t trust the media or your friends for spreading a lie? Blame the creators and those who spread it? Shrug it off, and look for the next meme? If you don’t want to get fooled, be more skeptical of anything you read—whether it is in a newspaper, a blog, a tweet, or status update. Just because it’s on a web page doesn’t make it true. The top-down journalism filter that once prevented lies from going public is now much less powerful. But journalism is now much more distributed. As such, it is a process and still capable, eventually, of getting the truth out.