Sidewalk Labs, the smart city technology firm owned by Google’s parent company Alphabet, released a plan this week to redevelop a piece of Toronto’s eastern waterfront into its vision of an urban utopia — a ‘mini’ metropolis tucked inside a digital infrastructure burrito and bursting with gee-whiz tech-ery.

A place where high-tech jobs and affordable housing live in harmony, streets are built for people, not just cars, all the buildings are sustainable and efficient, public spaces are dotted with internet-connected sensors and an outdoor comfort system with giant “raincoats” designed to keep residents warm and dry even in winter. The innovation even extends underground, where freight delivery system ferries packages without the need of street-clogging trucks.

But this plan is more than a testbed for tech. It’s a living lab (or petri dish, depending on your view), where tolerance for data collection and expectations for privacy are being shaped, public due process and corporate reach is being tested, and what makes a city equitable and accessible for all is being defined.

It’s also more ambitious and wider in scope than its original proposal.

“In many ways, it was like a 50-sided Rubik’s cube when you’re looking at initiatives across mobility, sustainability, the public realm, buildings and housing and digital governance,” Sidewalk Labs CEO Dan Doctoroff said Monday describing the effort to put together the master plan called Toronto Tomorrow: A New Approach for Inclusive Growth.

Even the harshest critics of the Sidewalk Labs plan might agree with Doctoroff’s Rubik cube analogy. It’s a complex plan with big promises and high stakes. And despite the 1,500-plus page tome presenting the idea, it’s still opaque.

Critics, including TechGirls Canada founder Saadia Muzaffar who resigned last year as an adviser to the project, have pushed back and loudly. The complaints have run the gamut, but many focus on the process itself, which opponents say lacked public engagement and was hijacked by a Google and its lobbyists.

“The proposal is theatre, it is misdirection,” said Muzaffar, who sat on a digital strategy panel guiding Waterfront Toronto, the government agency mandated to transform 2,000 acres of brownfield lands on the waterfront. “It is an attempt to get us to waste time being asked about the color of the wood the Trojan horse should be built with.”

This decidedly local plan has a global appeal. It could provide a model for other urban planners bewitched by the prospect of a modern, tech-centric city with sparkling infrastructure that somehow doesn’t push out middle to lower class residents. It’s a dream that hundreds of other startups trying to innovate around construction, land and financing are selling in cities around the world.

Nuts and bolts

Much of the draft plan (of which TechCrunch received in hard copy) focuses on Quayside and Villiers West, two sections of the waterfront that encompasses about 12.8 hectares, or 31.6 acres. Sidewalk Labs took more than 18 months to develop the proposed master plan, which was shaped, it says, by feedback and comments from 21,000 people — a data point critics contend is disingenuous.

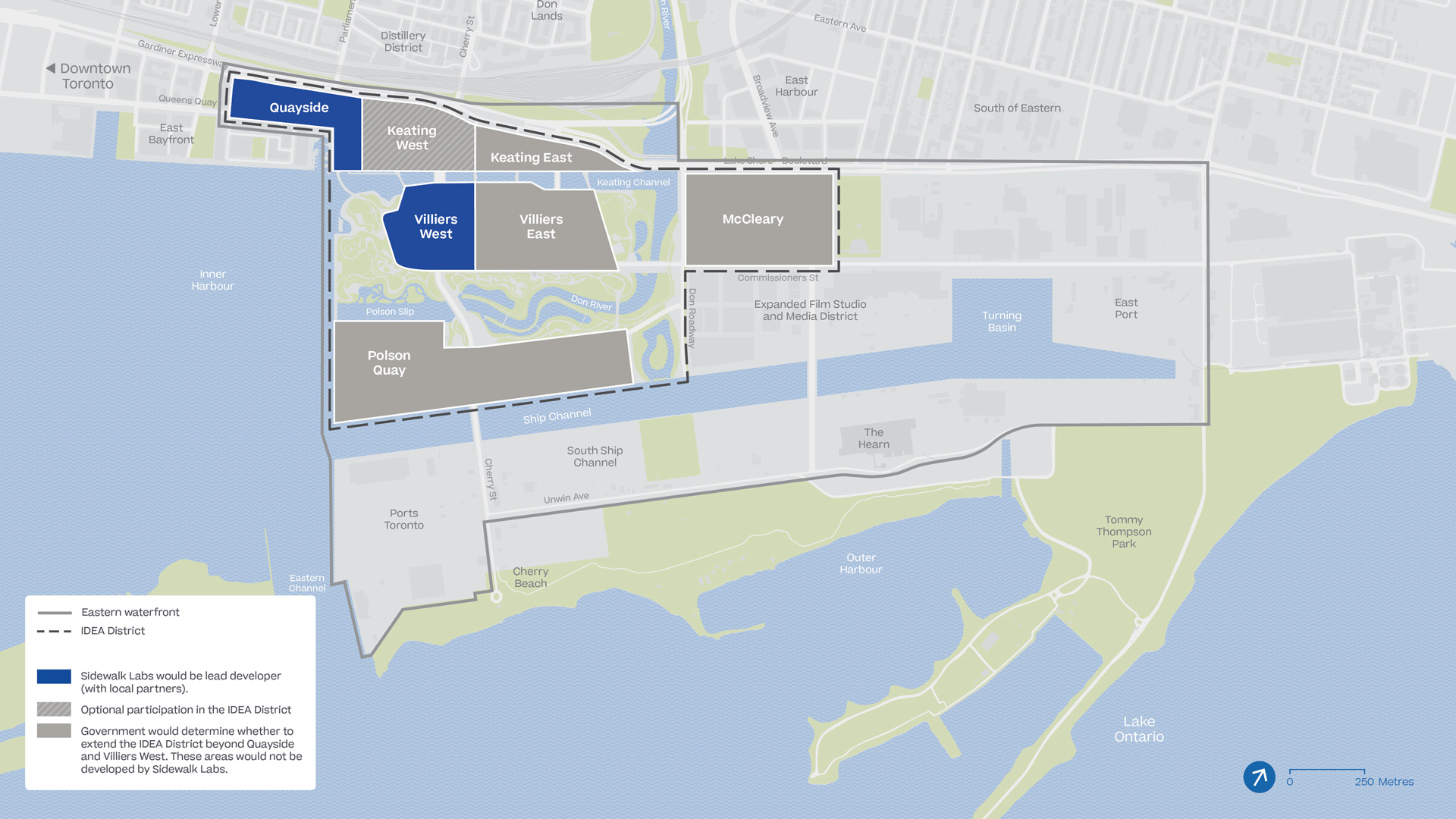

But Sidewalk Labs is already thinking well beyond Quayside and Villiers West. The plan proposes that if the innovations piloted in Quayside and Villiers West are successful, the government could expand them to a much larger area that Sidewalk Labs is calling the Innovative Development and Economic Acceleration (IDEA) District. The IDEA District, which can be seen in the image below and includes Quayside and Villiers West, is a 77 hectares, or 190 acres.

Sidewalk Labs’ ambitions extend beyond the size of the project. Even the Quayside and West Villiers piece has loftier plans than previously expected, including changes regulations and add mass transit.

The land for Quayside and Villiers West represents about 7% of the total eastern waterfront. Sidewalk Labs says it will invest up to $1.3 billion in equity and financing for this section, a mixed-use development that will include a mass timber mill, thousands of residential units, 40% of which will be priced below market, and a mobility system with adaptive traffic signals and heated bike lanes. Internet-connected sensors will track electricity use, air quality, pedestrian movement and even monitor park benches. A new Canadian Google headquarters on Villiers West island would be the capstone.

A report released Monday by Toronto-based consultancy urbanMetrics estimated that at its fullest scale, this plan would directly create 44,000 jobs, generate $4.3 billion in annual tax revenues and add $14.2 billion annually in Canadian gross domestic product.

The plan must be approved by the Waterfront Toronto Board and city council by winter 2020 for it to move forward.

Data mined and shared

Coursing throughout the Quayside and Villiers West development — and the larger IDEA District if it were to materialize —would be an open digital infrastructure. The foundation of this digital infrastructure would be a ubiquitous Wi-Fi network that uses a super passive optical network to reach faster speeds.

Sidewalk Labs would work with existing telecommunications companies to build out the Wi-Fi network. But it would play a larger role on other parts of the infrastructure such as erecting standardized physical mounts to allow for sensors to be installed in public places, building out a software-defined network and an advanced optical network.

A software-defined network works a lot like a home internet network on a much bigger scale. Residents would have their own private networks with no need to transfer or store information in the cloud. Meanwhile, the super passive optical network would increase speed while reducing the need for fiber optic cable. Super PONs split light into different wavelengths — each serving as its own signal over a single strand of fiber optic cable. The end result is a faster network which requires less fiber optic cable and uses less electricity.

The endpoints to this system will be sensors, which have the potential to be everywhere from traffic signals and park benches to waste receptacles, buildings and transit services like self-driving cars and shared bikes. Sensors have the ability to provide valuable information that can make a city run more efficiently. For instance, Doctoroff noted that a sensor on traffic signal could gauge whether a pedestrian needed a little extra time to cross the street.

It’s the data collected by these sensors — and the idea that such a large project would go to one company connected to a tech giant — that has concerned so many privacy and security experts. The Canadian Civil Liberties Union has sued and called for a reset on the project. The CCLU wants the government to protect it from the risk of “surveillance capitalism” before the plans goes through the approval process.

Jim Balsillie, the former chairman and co-CEO of Research In Motion, has also been a vocal critic. In a recent Globe and Mail opinion piece, he noted that smart cities rely on IP and data to make these sensors more “functionally valuable” and that growth at Google’s parent company is based on the “IP they own and the data they control.”

Sidewalk Labs’ Doctoroff insists that the plan already takes these steps. The data will be anonymized and the company said it will not sell personal information, use data for advertising or share it with third-parties without explicit consent.

Sidewalk Labs has also proposed that this de-identified data be shared with the public and that an independent, government-sanctioned Urban Data Trust to establish guidelines for data as well as approve and oversee the collection of information that apply to any entity operating in the development.

These promised protections weren’t enough to quell concerns. Even Waterfront Toronto, which selected Sidewalk Labs as its partner for the smart city project, admonished parts of the plan.

Waterfront Toronto, perhaps trying to get ahead of the anticipated blowback from the plan, emphasized that it did not co-create the master plan released Monday. Waterfront Toronto and Sidewalk Labs worked together early in the process on research, generate ideas, and consult the public. From here, the roles of the two organizations separated, Waterfront Toronto said.

While the organization said it was “excited” about certain proposals within the plan, particularly around environmental sustainability and economic development, it expressed concern about others such as the size and scope of the project as well as data collection, data use and digital governance.

The concept of the IDEA District is premature, Waterfront Toronto said in a statement. The organization also noted that Sidewalk Labs has proposed to be the lead developer of Quayside. Should the master plan move forward, Waterfront Toronto said it will lead a competitive, public procurement process for a developer, or developers, to partner with Sidewalk Labs.

Doctoroff also tried to get ahead of any concerns or criticism.

“Our involvement beyond Quayside is not guaranteed,” Doctoroff said. “We have to earn our way to continue with this project. And even if we do continue with the project our roles shift across the project the geography. Once we’re past Villiers West, we’re not going to be a developer of real estate.”

Opponents haven’t been spurred into action over the development of buildings or streets. This is largely about mining and controlling data. And while Sidewalk Labs made its own commitment to privacy and laid out several promises, it that doesn’t guarantee that third parties involved in the development would need to adhere to those same guidelines.

The debate over data isn’t confined to the Toronto project. The explosion of ride-hailing services several years ago caught cities by surprise. They wouldn’t let that happen again; and when scooters arrived on the scene one city already working on a solution sprang into action.

Last year, the Los Department of Transportation launched a digital tool called the Mobility Data Specification, or MDS, a set of API standards that allows cities to capture and analyze data from private mobility-as-a-service companies. The tool, which was introduced to help govern a year-long dockless scooter and bike pilot, is actually two APIs. One that lets companies send information to the city on the start, end and route of individual dockless vehicles like scooters and bikes. The other API lets the city send information and instructions to these private companies.

This anonymized data has given Los Angeles unprecedented insight into how people move through the city. Dozens of other cities have adopted MDS, prompting MaaS companies to push back. The conversation around data and the rise of MDS has led to the creation of the Open Mobility Foundation, a global coalition launched Tuesday that promotes using open-source technology to help cities manage transportation. Cities including Austin, Texas, Chicago, Los Angeles, Minneapolis, New York DOT, Portland, San Francisco, Seattle and Washington D.C. are founding members. Dockless scooter company Bird is also a founding member.

The MDS tool might be hugely helpful to cities, but it has its share of detractors, including Uber and privacy experts such as The Electronic Frontier Foundation who argue that even anonymized individual trip data could reveal a user’s identity. LADOT has since tweaked its policy to allow companies to send the data with a 24-hour delay; and it has issued guidelines on how data should be handled.

It wasn’t enough, however, to stop Assembly bill 1112 in the California State Legislature, which would have hamstrung cities’ ability to manage micromobility devices, including caps on total number of vehicles and requiring mobility companies to provide access to these vehicles in underprivileged communities. It would also ban cities from collecting individual trip data. That bill has been since postponed.

In the meantime, the Open Mobility Foundation aims to change how data is shared and used.

“This is new territory,” LA DOT general manager Seleta Reynolds said in a recent email to TechCrunch, noting that this is the first time a board comprised entirely of cities is convening to govern an open source code project. “Usually boards that govern open source projects are comprised of the industry that stands to benefit from the products built on top of it. This is the marketplace itself aggregating its power.”