In this section of my exploration into innovation in inclusive housing, I am digging into the 200+ companies impacting the key phases of developing and managing housing.

Innovations have reduced costs in the most expensive phases of the housing development and management process. I explore innovations in each of these phases, including construction, land, regulatory, financing, and operational costs.

- Reducing Construction Costs

- Reducing Land Costs

- Reducing Regulatory Costs

- Reducing Financing Costs

- Operations

Reducing Construction Costs

This is one of the top three challenges developers face, exacerbated by rising building material costs and labor shortages.

This is a heavily crowded and hot field that has been seeing a lot of activity in the past decade. Katerra, for instance, raised $1.2 billion of total financing. New venture funds have even formed to fund efforts like this such as Building Ventures. It’s hard to compete in a field that is saturated with lots of money and talent. Yet efforts that trend towards minimalism, such as the reinvention of manufactured homes or “naked” homes, have seen less activity by entrepreneurs and investors. Overall, there are many more startups that can be added here as construction technologies have entire maps of their own, but I focus on those that appear to or frame themselves around inclusion.

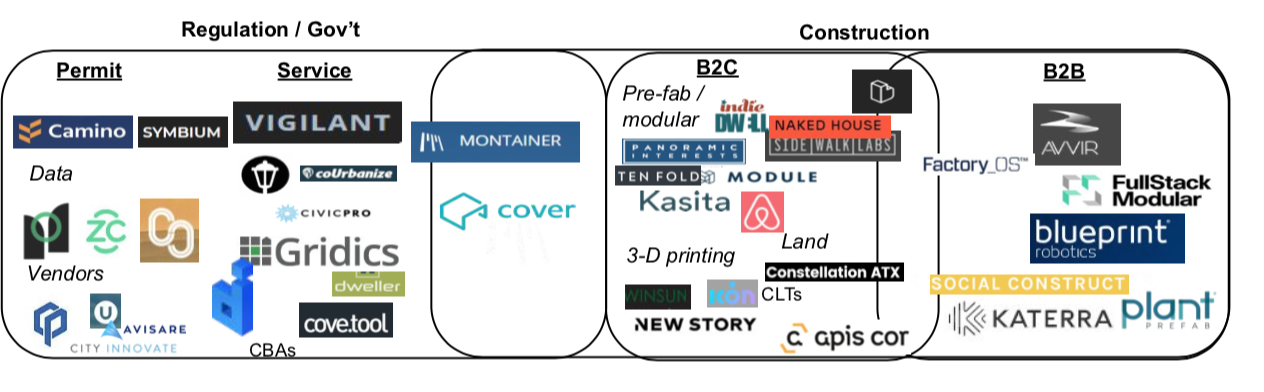

There are five main categories of housing construction startups.

The first category — and the most prominent — are those using prefabrication. Because these units are created in controlled, factory environments, prefabrication can purportedly reduce costs by 30% and completion times by 40%.

One subset targets other businesses. These startups include FullStack Modular, Blueprint Robotics, FactoryOS, Blokable, Rad Urban, Katerra, and Plant Prefab. Whereas most factories employ assembly line workers to create these units, Blueprint Robotics, a Baltimore-based startup, creates even greater efficiencies by using industrial robots common in automotive production lines.

Another subset targets consumers themselves, which include Module, Cover, indieDwell, and Panoramic Interests. Of special note, Module allows homes to “grow” with residents, helping them add space as needed. Cover is vertically integrated, creating a more seamless customer experience.

The best prefabrication startups will have mitigated numerous risks embedded in the model. Opening a factory for prefabrication involves high upfront costs. So during economic busts, many factories without diverse customer sources close. Beyond that, slim profit margins and highly dispersed plots of land in a largely suburban nation like the United States exacerbate operational costs.

The second category, though less popular, is 3D printing. While these interventions target emerging markets for now, companies like YC-backed New Story claim to be able to print a concrete housing unit in 24 hours. Other notable 3D printing companies include apis cor and WinSun in China.

The third category uses data analytics and robotics to reduce construction costs, often onsite. Skycatch’s drones, for instance, provide autonomous robots real-time feedback on the construction environment, dramatically improving the accuracy and efficiency of the robots’ work. Similarly, Avvir uses computer vision and data analytics to uncover construction inefficiencies and mistakes.

The fourth category reduces costs by simplifying furnishings and interior finishings, such as wall treatments, interior doors, and lighting — huge drivers of hard costs. Naked House provides homes that include minimal finishes, which can purportedly reduce costs by 40%. Social Construct “productizes” interiors finishings and mechanical, electrical, and plumbing materials, breaking down the insides of buildings into small, interlocking parts that save on construction time and cost.

The fifth category reduces costs by not building at all. In manufactured housing communities, for instance, homeowners typically provide their own housing unit, and simply rent the land at a discount from a landlord, who only needs to maintain the lot. Case in point: A traditional home in the Bay Area, for instance, can cost at least 8 times more than a comparable manufactured home.

Some developers are scaling this idea with micro-units. Constellation ATX, for instance, uses Kasita’s prefabricated homes as the manufactured home. It then rents lots to future homeowners. Three Pillar Communities is an investment fund focused on creating and redeveloping manufactured housing communities like these.

While manufactured housing has the potential to reduce costs, many owners suffer from high interest rates and other terms that some call predatory. Innovators here must be careful to pair fair financing with their efforts to further inclusive housing.

Reducing Land Costs

Driven by a lack of supply in major cities, land costs are one of the top three challenges.

Density

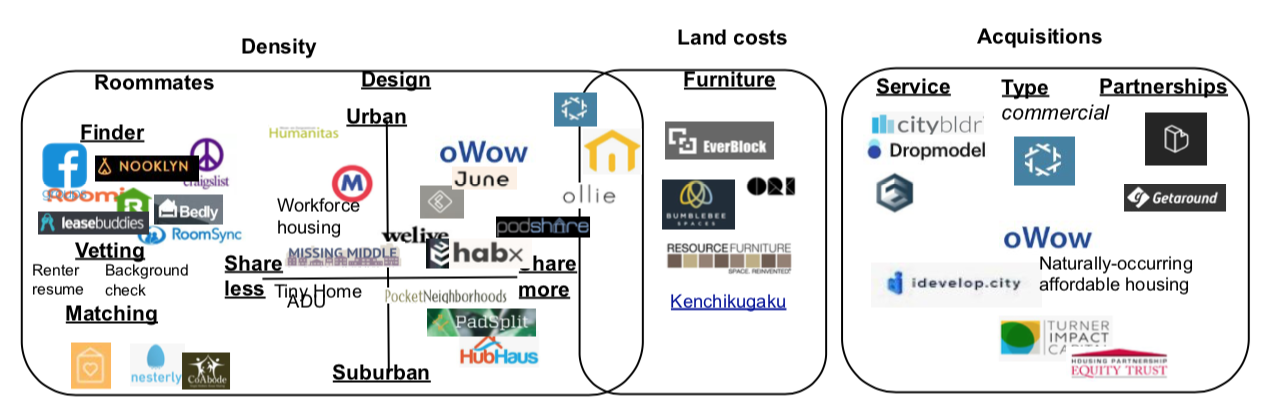

Housing can be designed to allow more people to share the same land. When that happens, often through roommates, upzoning, or more efficiently designed units (“microunits”), the cost of housing decreases for each person.

Innovations here are popular among entrepreneurs and investors, resulting in efforts by those of tech behemoths like WeWork. More can be done, however, to ensure that more density actually means more affordability. PadSplit and Starcity appear to be leading that effort.

Coliving efforts that target new audiences outside of professional millennials are also promising. Examples include a focus on families, such as Common’s and Tishman Speyer’s new venture Kin and “co-housing” or “pocket neighborhoods” that combine smaller units around a shared common space. With these innovations, families have more options than large, isolated single family homes.

There are two main types of design innovations. The first are those that provide living experiences themselves. The second are companies that use furniture and other tools to help people share living space.

On the first main design innovation, those that provide living experiences can be further categorized into two axes. The first axis is whether the organization is targeting higher density, urban areas or whether the organization is targeting lower density, suburban-like areas. For instance, accessory dwelling units (“ADUs”) or tiny homes are more common in areas with larger backyards or empty lots. These tend to be suburban or rural areas, not dense inner cities. In contrast, many of the most popular co-living companies tend to be in dense, urban areas, such as The Collective, Common, and Ollie.

Tony Anderson via Getty Images

The second axis is a rough measure of how much is being shared. For instance, companies that share more are more likely to share bathrooms, kitchens, and other furnishings, which result in further cost savings. These include PadSplit, HubHaus, and Starcity. Podshare and HomeShare go even further. PodShare tenants live in “bed pods” that lack doors or walls, while Homeshare allow some tenants to live in living rooms converted into bedrooms divided by cubicle-like partitions. In contrast, tenants in ADUs, tiny homes, and more expensive co-living units (such as WeLive) tend to share less, often having their own bathrooms, kitchens, and even living rooms.

To deal with denser living conditions, these innovations often help residents build communities that make sharing space more pleasant. Hubhaus, for instance, builds cultural groups to help residents living in close quarters enjoy each other’s company.

On the second main design innovation, there are two sets of tools that help people share space in a more livable way. The first set includes furniture tools that help people maximize their use of space. These include Bumblebee Spaces (robotics to store furniture in ceilings), Everblock (lego-block-like walls to form new rooms quickly), Ori (whose robotic furniture combines bed, kitchen, and storage), and Resource Furniture (which provides well-designed space-saving furniture, like wall/murphy beds).

Beyond furniture tools, the second set helps residents form better connections, turning the existing efforts of those like HubHaus into a platform. Cobu is a platform that helps residents connect based on any shared passion, while Building Impact focuses on volunteering and Meal Sharing and Resident focus on dinner hosting.

Roommates

Beyond these curated efforts to build living communities, a variety of tools exist to help renters find roommates themselves. Renters can save anywhere from 12-20% off their rent by living with roommates. Finding a roommate is a time-honored way to pool resources, increase bargaining power, and obtain economies of scale.

Given the clear need, this is a crowded field with huge incumbents like Craigslist and Facebook. There are a few differentiating efforts, such as those that pair underserved groups (such as Coabode’s focus on single mothers), diverse groups (such as Nesterly’s focus on the elderly with the young), and more roommates (so that roommates can form larger groups and obtain better economies of scale).

Roommate apps range from tools that help you reduce transaction fees from rentals (e.g., Naked Apartments or the “no fee” search on Streeteasy), find roommates (Roomi, Bedly, Facebook, Craigslist, and others), vet roommates (Checkr’s and Roomi’s background checks), and match with roommates that meet your preferences (such as Welcome Home’s living preference algorithm).

Hoxton/Tom Merton via Getty Images

Some work-trade roommate platforms pair landlords willing to provide discounted rent in exchange for roommates who can offer help around the house. Nesterly, for instance, pairs seniors with millennials and other renters who want to save money and can help around the house. Others pair underserved populations together, such as single mothers (CoAbode) and the elderly (Golden Girls Network).

Acquisitions

Find diamonds in the rough. Purchase high-potential land at a lower price. If inclusive housing entrepreneurs can purchase land cheaper, they can pass those savings onto renters and future owners. But as I note above, affordability is not guaranteed. Investors, unless socially-motivated, are likely to capture the savings themselves.

There are three acquisition innovations to consider.

The first are services that help developers understand where to purchase. Citybldr, Envelope, idevelop.city, and Parafin use large datasets, regulations, and/or algorithms to understand which properties to acquire and how to develop them. For mom-and-pop investors and real estate brokers, Dropmodel eases due diligence for real estate investments.

Citybldr has the potential to help achieve economies of scale in housing. It helped a group of homeowners in Seattle sell their homes for nearly 40% more than if they were to sell individually. By doing so, Citybldr incentivized more to sell, including those who may have otherwise been resistant to new development efforts. By grouping parcels of land, developers obtain more space for land to develop larger, higher-density developments.

The second are services that acquire underutilized types of housing. Empty lots behind buildings can be used to build housing such as accessory dwelling units. Brownfield Listings helps developers find vacant buildings, such as factories or warehouses, which E-lofts and Starcity convert into housing units. Turner Impact Capital and Housing Partnership Equity Trust buy and keep older, multifamily projects affordable for the long-term.

The third are partnerships that unlock more value out of land. One housing startup, Blokable, partnered with a church to produce a 3-story apartment complex on the church’s empty lots. By working with the car-sharing operator Getaround, one developer saved itself from building 71 spots of parking.

Data-driven efforts to acquire real estate for housing are accelerating. It’s likely that many sophisticated developers have such tools in-house. Yet efforts like the above help more people benefit from data analytics. I’m excited about efforts, like Citybldr’s and Blokable’s, where the whole leads to more value than the sum of its parts.

Reducing Regulatory Costs

There are a variety of services that exist.

One set of tools helps developers navigate local politics. coUrbanize and Neighborland engage those that do not have the resources to participate in time-consuming development processes, as I discussed in Hacker Noon. Anti-development behavior is a major blocker of development projects.

But tools like coUrbanize have helped affordable housing developers get approvals on schedule. Created in the last 20 years, community benefit agreements have also successfully helped developers obtain support from local organizations.

Another helps developers navigate zoning codes. Gridics and Symbium (with a focus on ADUs) help developers visualize zoning codes and development possibilities with a specific parcel. Camino.ai helps governments and the public navigate zoning, permitting, and licensing applications better.

Bombaja via Getty Images

CivicPro provides local regulatory intelligence about changes in codes and policies. Other companies like Upcodes integrate code compliance directly in building information modeling software, reducing compliance errors and thus costs.

Targeting a more lay customer, Cover and Dweller helps local homeowners add code compliant, prefabricated units to underutilized land, like backyards and empty lots. By asking a series of questions, Cover gathers data about its customers and then generates a code-compliant ADU that can immediately be purchased and installed.

While less technology-focused, Dweller focuses on affordability and also provides financing, a painful barrier for many would-be ADU purchasers. In return for paying for the upfront costs of constructing and permitting the unit, Dweller owns the ADU and receives a portion of the unit’s future rent.

As I will further discuss in this package’s conclusion, this is a promising and overlooked area. Regulatory politics and compliance is a painful and expensive part of the process of developing housing. This field will grow as legal technologies (“legaltech”) and regulation technologies (“regtech”) continue to expand.

With the help of such technologies, more people may be able to navigate contractual, regulatory, and government affairs issues easily.

Furthermore, discovering regulatory opportunities can help businesses target new markets and reduce operational costs. Take, for instance, the example of the Oakland developer that avoided expensive parking requirements in the zoning code by partnering with a car sharing provider.

Through technologies like these, end users will be better protected from harm without completely stifling innovation.

Reducing Financing Costs

Raising enough money for a new project is one of the biggest hurdles for a development project.

Social Impact funds and crowdfunding

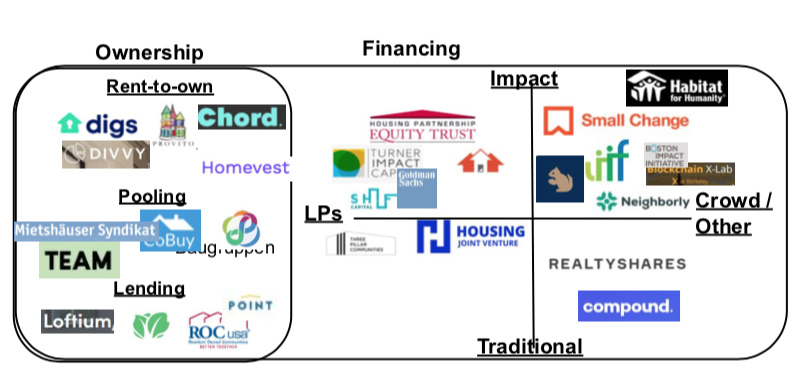

Financing innovations come in two main categories: impact-oriented or crowdsourcing.

Social impact funds focus on both profit and social impact, such as Turner Impact Capital and Housing Partnerships Equity Trust. These investors have discovered that buying “naturally affordable” older properties and keeping them affordable can be good business.

Since demand for lower rent increases during recessions, such units act like bonds in economic downturns. Raising a private fund has other critical advantages too. Housing Partnerships Equity Trust, which is led by a group of nonprofits, found they could close deals faster than if they relied on public financing.

For similar reasons, city governments have also invested in quasi-private housing funds, such as the city of San Francisco’s investment into the SF Housing Accelerator Fund.

Using a data-driven approach, Perl Street raises money to finance urban technology startups, including those in the housing sector. By using diverse data sources to boost growth and reduce the risks of their portfolio companies, Perl Street offers a unique investment approach.

Pattanaphong Khuankaew / EyeEm via Getty Images

Some funds raise money from a diverse group of people, including retail investors. This method is often called crowdfunding. Small Change, for instance, first rates developments based on key impact criteria such as affordability, and raises money from retail investors for those projects. The Low Income Investment Fund’s Impact Note raises money from investors who want to co-invest in affordable housing projects.

There’s a decent amount of competition and interest in this space. In addition to competing with numerous traditional real estate crowdfunding sites, such as RealtyShares or CrowdStreet, these funds have to compete against REITs and other low-friction, highly-liquid equity investments.

Yet, this space has potential opportunity to help housing innovators more. In my conversations with coliving, ADU, and micro-unit developers, innovators have a hard time getting cheap financing typically reserved for single-family homes.

Small Change, by garnering socially-conscious investors, and Perl Street, through its use of data, have been able to obtain cheaper financing for alternative housing forms. But more work is likely needed to create models that can scale such efforts well.

Renter ownership

Some models raise money from the tenants or future residents themselves to promote renter ownership and development.

One model involves residents pool together money to purchase a larger home together. CoBuy, for instance, allows future residents to pool money (also often called “collaborative mortgages”) and ease the process of purchasing a home together.

Baugruppen is a model of development where future residents pool financing and become developers themselves. While traditional developers require 10 to 25 percent returns on their capital, citizen-developers, since they simply care about living in the units, do not require such high returns. Housing costs, as a result, drop.

Yet residents may often not have sufficient funds to afford a mortgage. To deal with such issues, Mietshäuser Syndikat provides discounted capital from an association of other like-minded housing groups. These groups form a co-housing financing syndicate whose goal is to create more permanently affordable housing projects.

ROC USA secures loans for low-income manufactured housing residents to purchase their community from a landlord. Residents form a newly-formed cooperative, which technically owns the land itself. The cooperative form is called a limited equity cooperative; the resale values of the tenant’s share are limited to promote long-term affordability.

Aside from providing low-cost funds, other innovations help individual residents raise money by taking a cut of the owner’s future profits. Landed provides down payment assistance to “essential professionals,” such as teachers, and has a right to share in the future appreciation of the home.

Point works similarly, but any homeowner, not just educators, are eligible. Loftium reduces rent for prospective renters, provided that they share additional income they generate from sharing economy sites, like Airbnb.

In limited areas, Loftium and Kabbage also provides a down payment and other forms of capital, provided that they keep the cash flow from future Airbnb rentals.

The final intervention identified here provides upfront capital in exchange for a premium later on. Called rent-to-own, or shared equity schemes, companies like Divvy make money in three primary ways.

First, tenants pay for a “lease option” that gives the tenant an option to buy the house. Second, the tenant purchases the home at a price higher than Divvy’s initial purchase price (in one example, at a 11% premium). Finally, renters make extra payments that go towards maintenance and ownership “credits.”

If they decide to go elsewhere, these payments are forfeited (though, in the case of Divvy, maintenance funds at least appear to be returned). Other variations exist, including that of Provito and Homevest, which uses security deposits to help renters obtain ownership.

Rent-to-own interventions may help more people purchase housing, especially those with poor credit scores. Yet consumer advocates say that, if not executed carefully, tenants may be burdened by both the risks of renting, including the possibility of eviction and high monthly payments, and ownership, including extensive maintenance costs.

Given that many are locked out of ownership, this is a burgeoning field with large amounts of need. I’m particularly excited about new models, such as CoBuy and ROC USA, that leverage group buying power. ROC USA, in particular, promotes long-term affordability, which many interventions overlook.

By pairing group purchases with limited equity cooperatives, ROC USA helps future would-be homeowners — and many generations beyond — to continue to afford ownership, even if true market property values in the neighborhood have escalated many-fold. There are significant opportunities to use law, technology, and finance to scale such models like ROC USA.

Operations

Aside from developing housing, operational costs, whether they include utility, property management, or legal costs, have a large impact on the tenant’s overall housing costs.

Part of a thriving and competitive ecosystem of property technology (“proptech”) and real estate technology (“retech”), the following categories deserve (and have) maps of their own. To identify those that may reduce operational costs, I highlight key examples that may also filter savings to end users, such as renters and homeowners.

Utility costs

As I detail in Hacker Noon, utility costs (electricity, gas, water, and sewage), from one analysis of public real estate records, add 25% to homeowners’ costs and up to 27% to renters’ costs. The biggest utility culprit is energy — electric and gas take up 49% of total utility costs. It’s clear, then, that more energy-efficient and energy-producing units mean more money for residents.

Portable tools help reduce energy costs, such as smart thermometers (Nest) and outlets (ThinkEco). New financing tools to help renters and property owners afford energy-efficient retrofits. These tools include increasing the renter’s utility bill (also called “on-bill financing”) such as that of Matter.solar, or the crowdfunding efforts of BlocPower and Mosaic. Finally, innovators are targeting energy sources themselves. Smart energy retailers (Drift) use analytics and a marketplace to save costs. Community solar farms (Solstice) and microgrids (Lo3 Energy) enable even renters to obtain and invest into the production of new sources of energy.

Property management costs

Property management companies can charge anywhere from 7% to 10% of rent just to manage daily operations, and, even then, offer variable service. Keyo, for instance, focuses on brokerage and leasing. Active Building, Zenplace, and Bixby help with renter management, while Boodskapper specializes in maintenance.

Some tools are focused on benefiting renters

These interventions help managers increase their market and reduce turnover. To ease the financial hardship of renting, Rhino and The Guarantors overcome barriers caused by security deposits and income limitations. Stake reduces turnover rates by offering a loyalty program that invests a portion of rent into a stock fund the longer a renter stays in the building. Till provides renters threatened with eviction with loans to stay in their apartments.

Part 2 and the conclusion of this report will be published tomorrow.

Please feel free to let me know what else is exciting by adding a note to your LinkedIn invite here.

If you’re excited about this topic, feel free to subscribe to my future of inclusive housing newsletter by viewing a past issue here.