The inability or unwillingness of many venture-backed startups to go public is starting to sting.

Backers of venture funds are increasingly leery about putting more capital to work in the startup landscape without getting some of their prior cash back. But with IPOs not expected to pick up for quarters longer, and the backlog of richly priced startups stretching long into the distance, there’s little expected in the form of relief on the horizon.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

But that doesn’t mean that some companies aren’t going public. They are! And some of the newly public entities are even venture-backed or at least clothed in the language of tech companies. Their IPOs have been crushing successes. This is somewhat embarrassing for what we might call the traditional center of tech and startups: software companies.

The stonking Cava public offering (privately backed fast-casual food with e-commerce elements) was joined this week by the debut of Oddity, a beauty-focused company that screams about its use of modern technology tools to create its products. Oddity, like Cava, priced above its final IPO price range and shot higher in the wake of starting to trade.

The stonking Cava public offering (privately backed fast-casual food with e-commerce elements) was joined this week by the debut of Oddity, a beauty-focused company that screams about its use of modern technology tools to create its products. Oddity, like Cava, priced above its final IPO price range and shot higher in the wake of starting to trade.

Food? Beauty? Certainly these are consumer product categories that build big brands, big businesses, and material cash flow in certain circumstances. But they aren’t, you know, tech-quality in their growth and gross margins, right?

Have I got news for you.

Perhaps there’s something to the intra-tech conversation today asking why software companies aren’t more profitable. After all, if you have high-margin recurring revenue and can’t balance the books, are you really that business savvy?

Lessons, learnings

There’s a discussion in tech that the idea that software companies will grow and become increasingly profitable over time is at least partially incorrect. While the most valuable companies in the world sell software products, smaller firms that sell access to SaaS products are often unprofitable and unable to truly demonstrate operating leverage.

Though tech companies of many sizes have become more profitable in recent years, the fact that many software shops continue to post massive GAAP losses or even adjusted profitability metrics in the red is a puzzler!

I claim no truly groundbreaking insight here, but I would argue that the following is partially at play:

- Companies valued on a multiple of their revenue are taught from a very young age that they should spend all their cash flow — and more — because the math will always shake out later.

- In contrast, companies that are profitability minded have a different operating posture than companies that are purely growth focused.

- Critically, growth-focused companies (those valued on revenue multiples and not profitability metrics) put off swapping profits for growth to avoid an awkward period of transition; thus we often see tech companies growing at unimpressive rates, busy avoiding truly evolving their soul in hopes of staying valued on revenue growth instead of profitability.

It’s also harder to be profitable in the near-term when you sell software for a series of smaller checks. In SaaS-o-nomics, you spend all the money to build, QA and sell software, and then collect the value of sales over time. Sure, with enough net dollar retention you can wind up better off in the future, but the nearer-term cash-flow results can prove downright nasty.

I brought you through all of this to point out that while it is eminently defensible to say that software and especially software-as-a-service companies are valuable, it is also accurate to say that they aren’t the only high-margin ponies at the show.

Cava’s 2023 IPO, backed as it was by venture and private-equity types, caught our eye. The restaurant chain’s quick growth and history of adjusted profitability was notable. Here was a company on the move, expanding its top line while generating positive operating cash flow.

And investors loved it. As we reported at the time:

After setting an initial IPO price range of $17 to $19 per share, later raising the interval to between $19 and $20, Cava priced at $22 per share.

The fast-casual restaurant chain is not TechCrunch+’s usual topic fare, but as the company was heavily backed by private capital during its early life — including some venture capital dollars — and how starved we have been for any data on how public-market investors would react to new growth stories, well, we’ve paid attention.

So, too, were the public market types, it seems, as Cava shares opened today at $42 per share and are currently trading at $42.33, up more than 92% from the company’s IPO price.

And then, this week, there was Oddity Tech. The Israeli company priced at $35, above its raised IPO range, and then saw its value expand by nearly 50% during its first day’s trading. Not bad!

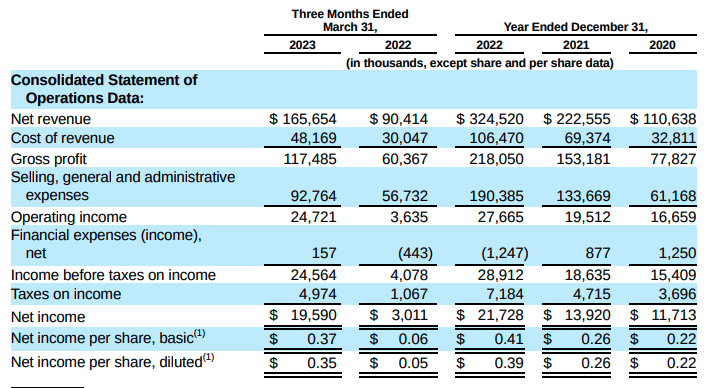

Avoiding its tentative second-quarter results and sticking to its more-solid Q1 2023 data listed in its F-1 filing, observe the following:

Image Credits: SEC filings

Let’s see: Adding $100 million or more in revenue per year? Check. Rising operating income across recent years and in its most recent quarterly update? Yep. Actual GAAP net income to go along with operating profits? Certainly, and always on the rise as well.

It’s almost weird to read an IPO filing and not make mental excuses while doing so. Normally we see a quickly growing software company that loses money and start muttering in our heads things like Well, yes, but the company is in investing mode and thus is paying today for tomorrow’s cash flow and the like. We don’t have to do that here! And investors love it!

Per Yahoo Finance data, Oddity is now worth around $2.7 billion, making it a multi-unicorn and one that, while certainly tech-enabled, sells something pretty far from what we’d normally consider a tech product.

All of this is very embarrassing for software companies. Supported by an ocean of loose private capital, given a decade or more to get public, and yet, here we are. More money flowed into software startups than we’ll probably see for a generation, and the resulting crop of tech startups is stuck on the vine while companies that sell food and beauty products are partying and posting ripping IPOs. Ouch!

No matter where you sit in the “Why aren’t so many tech companies more profitable?” conversation, it’s clear that something has gone sour in the startup-venture-IPO pipeline. And at least so far, there has been far too little visible contrition. Perhaps there should be some more of that.