Well, those Bird results were wrong.

It recently came to light that Bird, a former startup unicorn in the once-hot scooter rental market, overstated its revenue for several years, leading to the company stating in a filing with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission that several of its “audited consolidated financial statements [ … ] should no longer be relied upon.”

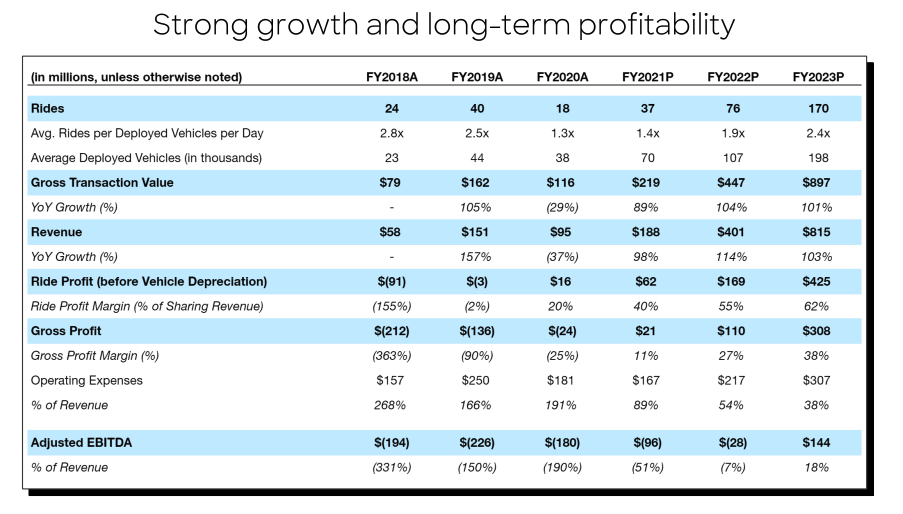

The errors impact the company’s results for 2020 and 2021, along with the first two quarters of 2022. Given that Bird announced its plan to go public by merging with a special purpose acquisition company in mid-2021, a transaction predicated on its trailing results, the accounting mess is consequential.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

For many investors, we reckon that the admission of error is a bit too late. Back when the Bird-SPAC deal was voted on, shares of the blank-check company fell. And then kept falling. Since the merger of the two companies, Bird has lost nearly all of its value, falling from a 52-week high of $9.05 per share to just 30 cents per share as of early morning trading today, according to Google Finance data.

More simply, Bird lost nearly all of its value after going public, which we presume means that some regular folks took a bath. Now it turns out that it went public using partially incorrect historical data. Even more, the company’s latest earnings report notes that as of the end of Q3 2022, Bird “will not be sufficient to meet the Company’s obligations within the next twelve months” with its existing cash balance of $38.5 million.

Essentially worthless, nearly out of cash and unable to control its books? Bird’s implosion is perhaps a fitting cap on the excesses of the last startup boom.

Essentially worthless, nearly out of cash and unable to control its books? Bird’s implosion is perhaps a fitting cap on the excesses of the last startup boom.

Why the Bird accounting error is particularly vexing

Looking back, the Bird and Lime startup experiment was a waste of capital brought on by a period of history when cash was incredibly cheap.

The two startups raised simply staggering amounts of money from private-market investors only to spend it on massive market reach that they couldn’t sustain (Bird, per its latest earnings report, recently exited three European countries), hardware that went bad and more. (It’s hard to imagine the two companies raising that sort of money for scooters today, so perhaps the 2022 venture market really does have something going for it.)

Update: Lime emailed in flagging its recent performance, noting that, unlike Bird, it added staff and markets this year. It also shared some color on profitability that I will dig into further in a future post. The above was an attempt to summarize a few years of frenetic activity, not to argue that Bird and Lime are in the precisely same shape today.

But let’s push past the past. The Bird accounting mess is particularly frustrating not due to the history of the company, its competition and how it used cash. Instead, it’s because of how Bird pitched itself when it did go public, opening up its equity to nonprofessional investors.

To understand why we’re irked, let’s start with how Bird describes its accounting issue:

[A]n error identified in connection with the preparation of the Company’s condensed consolidated financial statements [ … ] related to its business system configuration [impacted] recognition of revenue on certain trips completed by customers of its Sharing business for which collectability was not probable.

In its earnings call, the company expanded on the matter. Here’s CFO Ben Lu (via a Seeking Alpha transcript):

During the evaluation of a rider wallet subledger, we found a design error within our internal backend IP systems. The systems did not capture some failed payments occurring after the completion of a ride that were incorrectly booked as revenue, resulting in the overstatement of revenue and understatement of deferred revenue.

It’s worth noting at this juncture that Lu and new CEO Shane Torchiana took on their roles in September of this year. The mess above is not their fault, though it is their job to clean it up.

How much cleanup is there? Again per Lu:

As a result, we expect to restate our historical revenues by $12.5 million in the first two quarters of fiscal year 2022, $14.6 million in fiscal year 2021 and $4.5 million in fiscal year 2020.

How do the above restatements impact prior results? Let’s run the math:

- Reported 2020 revenue: $94.6 million

- Actual 2020 revenue: $90.1 million (-4.8%)

- Reported 2021 revenue: $205.1 million

- Actual 2021 revenue: $190.5 million (-7.1%)

- Reported Q1 and Q2 2022 revenue: $114.6 million

- Actual Q1 and Q2 2022: $102.1 million (-10.9%)

Are those big changes? Yes. Any accounting mistake that involves the restatement of several years of results is a big deal. That the errors reached double-digit percentages in 2022 is downright terrifying.

Still, you might think that at a company with a market cap of around $75 million and a share price of around a quarter (per Google Finance data pre-market this morning), a few issues are just par for the course. Look again at the misstatements. In percentage terms, they get larger as time goes along. This means that Bird was slightly wrong about its 2020 results, more wrong about 2021 and most wrong about this year.

Put another way, things really went off the rails as it went public, meaning that regular folks were more likely than other investors to get hosed by its errors.

If a professional investor putting third-party capital to work gets hoodwinked, we expect lawsuits. When regular folks get a surprise bath from a company unable to understand its own business, we’re a bit more annoyed. (That SPACs are now once again out of fashion after incinerating so much wealth is fine, but we’re waiting on the accountability portion of the saga.)

To cap off why the Bird issue is stuck under our fingernails, let’s revisit how it pitched itself when it wanted to merge with a SPAC:

Image Credits: Bird investor presentation

The 2020 number is wrong, we know that. But look at the 2021 estimated figure and compare it to what Bird originally reported and what it has now admitted. A revenue beat is now merely a meet. The company is now even farther away from the revenue pace it would need in 2022 to meet its prior projections. Bird reported Q3 2022 revenues of $72.9 million, meaning that it has done less than half of the revenue it projected for last year through the third quarter of this year. Whoops.

The revenue errors made Bird look better than it was. It turns out that some of the plumage was false. And it made the errors while going public. For shame.