You’d expect an expense management company to have a large sales department and advertise through all kinds of channels to maximize customer acquisition. But like we’ve seen over and over through the course of this EC-1, Expensify just doesn’t do what you think it should.

Keeping in mind this company’s propensity to just stick to its guts, it’s not much of a surprise that it got to more than $100 million in annual recurring revenue and millions of users with a staff of 130, some contractors and an almost non-existent sales team.

If you’re wondering how it’s possible to grow to such a level without an established sales team, the short answer is: Word of mouth.

If you’re wondering how it’s possible to grow to such a level without an established sales team, the short answer is: Word of mouth. To an extent, Expensify can do this due to the space it’s in, as expense reporting is such a thankless, almost mind-numbingly boring task that anyone who found a good solution is bound to recommend it to their colleagues and friends.

But it’s more interesting how Expensify grows bottom-up within SMBs, its core customer base. By providing an easy and meaningful experience via the product itself, the company has come to a point where it only takes one or two users who love the service to turn their company into customers.

This approach flips the traditional sales model on its head and is now known as product-led growth, but Expensify did it long before it was an accepted business model. Though that was harder than it sounds, it also put the company in a uniquely privileged position, which it is fully intent on leveraging.

Starting the flywheel

There are many ways to get such a business model started, but as usual, Expensify threw caution and all advice out the window and banked on turning its users into evangelizers for its product.

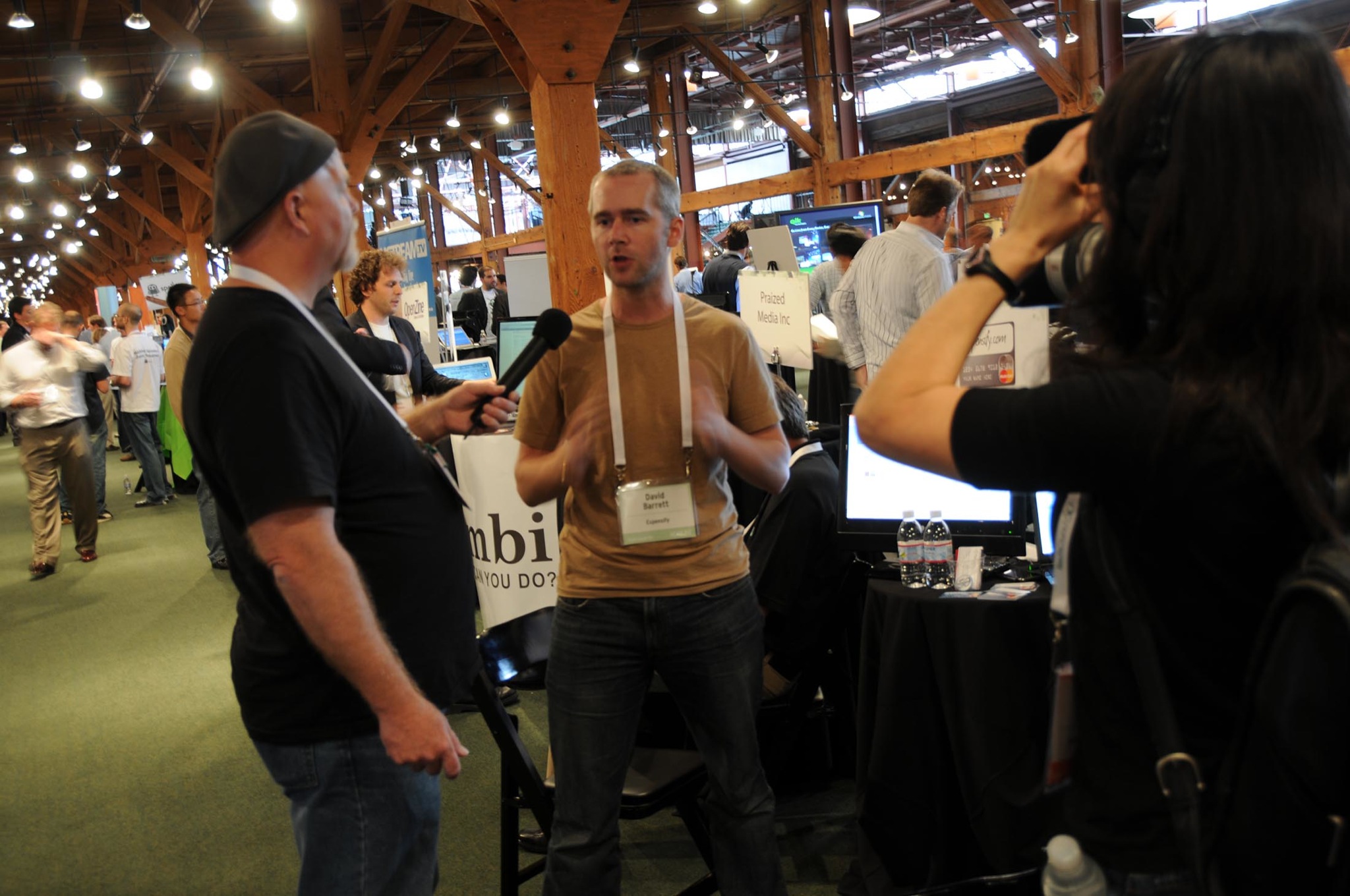

As we saw in part 1 of this EC-1, Expensify CEO David Barrett had been working solo on the project until he applied for the TechCrunch50 2008 conference, where he launched the company with co-founder Witold Stankiewicz. Their pitch was a combination of a corporate card and expense reporting, and the latter clearly resonated more with the audience, Barrett recalls.

The viral loop started when Expensify won second place at Demo Pit, an earlier version of our Startup Alley. The startup soon received some press coverage and quite a bit of attention from what we now call influencers. “That awareness really helped supercharge our word-of-mouth business model,” Barrett said.

David Barrett being interviewed in the DemoPit at TC50 2008. Image Credits: JD Lasica

It helped that the people at the conference were precisely the customers who Expensify was targeting, as they all presumably had travel expenses to report. The co-founders had realized by then that there are more people who need to report expenses than there are accountants, which helped it fine-tune its targeting.

Expensify also happened to be at the right place at the right time, especially with its mobile receipt scanning feature, as smartphones were just hitting the mainstream. It was actually a bit early, as the demo was more of a proof of concept than what iPhone cameras could do at that point.

Nevertheless, mobile had started to empower the populace, and companies were taking note. This was the rise of Bring Your Own Device and it was the perfect moment to suggest that employees could pick their own expense reporting tool.

The SMB greenfield

A pitch aimed at employees would probably not have fared well at major corporations, but they weren’t Expensify’s focus. Rather than competing with enterprise-focused incumbents like Concur, Expensify found that there was an opportunity to win over people who were reporting expenses with spreadsheets or manually. As Barrett soon learned, most of these people were running or working for SMBs, and they weren’t the terrible customers he was being told to dismiss.

Instead, it turned out to be a boon. “My experience with SMB from the very start was so different than everyone else’s. I think we quickly came to learn that the SMB is like the land before time. It’s this market that no one thinks about, especially in Silicon Valley, because everyone is so obsessed with the enterprise that they’re just missing out on the biggest opportunity,” Barrett says.

Yet, almost half of American employees work in small businesses, which accounted for over 50% of net job creation in 2014. “So if you have a business model that benefits through revenue expansion, like we do, as we charge on an active seat basis, doubling in SMB is much easier than doubling in enterprise, from a seat perspective.”

Barrett also found that the SMB market was where a top-down sales model shows its limits and a bottom-up sales approach shines. “Every time you submit an expense report, you basically refer us to your boss, who’s the decision-maker,” Barrett said.

The company’s word-of-mouth focus also helped bring in more customers, as it’s easier for employees at small businesses to make themselves heard than in a large corporation. “Every customer we have starts with some individual employee downloading the mobile app for free because a friend told them to, and then they just started using it,” he said.

It’s hard to overstate how big an impact this customer acquisition model has on the company. With users evangelizing the product in a market where businesses don’t shop around for solutions, there’s no need for an outbound sales team or traditional advertising.

Instead, the key is to offer an outstanding user experience that will win customers and retain them. SMBs don’t churn easily, since they don’t typically review their contracts unless there’s an issue. And perhaps counterintuitively, they are also less price-sensitive than enterprise clients, which constantly seek savings.

2011 billboard — an exception to the rule. Image Credits: Expensify

Expensify also took an unusual approach to pricing. The service was initially free to use, since the founders had raised about $1 million and had a lot of runway, but they had to start charging because early feedback revealed that being free made the product somehow less trustworthy. To fix that, the company decided to design its pricing so that Expensify would remain free for the vast majority of users.

It could afford to do so thanks to its tech-enabled approach and to the zero marginal cost nature of software in general. All of this compounded its product-led growth, which led to a large influx of customers big and small, and revenue skyrocketed.

With such a demonstrably successful business model, you’d think VCs would be fighting for a position on the cap table, right? But that was far from what happened.

While investors did reach out after TC50, Expensify long felt out of tune with much of the startup investment community due to its approach to sales. Director of product and customers, Jason Mills, says, “We reached a turning point where the market seems to value the kind of business that Expensify has, but it wasn’t that way for a very long time.”

“I realized we were on a different path and I couldn’t count on the VC community to get me there”

Product-led growth just works for businesses like Expensify. Over the past few years, Slack, Zoom, Dropbox, Airtable, Asana, Coda and Figma are just a few of the success stories that proved this business model works.

Blake Bartlett. Image Credits: OpenView

However, it wasn’t really a popular one around 2008. “With Atlassian and SurveyMonkey, there were established businesses doing this, but it was very much the exception, not the rule,” OpenView partner Blake Bartlett told TechCrunch.

It wasn’t just about bottom-up SaaS either, as even SaaS as a whole wasn’t what it is now. Recurring revenue was attractive, but there was still uncertainty as to whether enterprise clients would come in as customers and how widely a business could scale. The idea that a company could skip traditional sales altogether just seemed too good to be true, and most thought it was a short-term model.

For Expensify, this skepticism was sometimes destabilizing. “It just felt like we were crazy,” Barrett says.

Expensify still managed to raise money. Until it didn’t.

Barrett recalls that fundraising hadn’t been hard until 2013, as the gap between his plans and the traditional approach could still be swept under the rug — VCs assumed he’d come around to a more traditional approach eventually. However, something changed when he pitched “every top firm” in Silicon Valley only to get turned down.

Their argument was that Expensify’s numbers were “incredible” and that the company wasn’t explaining clearly enough what went into it. This was understandably frustrating, but also led to an epiphany. “At that point, I realized we were on a different path and I just couldn’t count on the VC community to get me there,” Barrett says.

Which led to another question: “Why am I talking to them anyway?” After all, being profitable had always been on the roadmap, but it was time to fast-forward. CFO Ryan Schaffer, a new marketing hire at the time, remembers it well: “David called an all-hands and basically said, ‘All right, I did not take the round that we were all just counting on. So we need to get profitable and we need to do it quickly.’”

Inevitably, the focus on profitability involved sacrifices such as a companywide pay cut, a hiring freeze and a serious look at expenses, but it wasn’t enough. It got the company out of the danger zone, but Barrett knew that they needed more. “Being a little profitable is like having your chin barely above water. [It] is not very fun at all,” he says.

This set his next goal of making Expensify “wildly profitable.” To tackle the biggest roadblock of reducing customer support costs as revenue grew, the company decided to double down on self-service and introduced AI into the mix. It also slashed its traditional marketing and advertising budget. “And since then we’ve kind of just been on a big upward trajectory,” Schaffer said.

“Okay, now VCs trust us again”

Maximizing revenue growth while increasing cost-efficiency did wonders for Expensify’s bottom line. And with profitability came the freedom to choose.

Without an urgent need to raise funding, the company now had more leverage with VC firms, and perhaps more importantly, the time to look for investors who were ready to bet on its business model.

Eventually, Barrett found several new investors willing to back his vision, including Rahul Prakash at NOMO Ventures (formerly Coyote Ridge Ventures), David Martirano at PJC (the acronymized Point Judith Capital), and soon afterward, Bartlett at OpenView.

“Interestingly, by the time we got to the period where we were like, ‘Okay, now VCs trust us again,’ we didn’t need them anymore,” Barrett said. With that in mind, Expensify wanted to raise as little as possible to limit dilution and the distraction of having too much money on the balance sheet. It had some leverage, but its new investors still had some targets, which Barrett explains drove the company to “a lot of secondary deals” to make space on the cap table.

However, Expensify was still wary of diluting its equity — so much so that it chose to raise debt instead of pursuing more VC deals. “Maybe that strikes some people as weird,” Schaffer explained, “but we view debt as better than raising equity, because you can never get back the equity you sell to a VC.”

A primary reason for raising debt was that the company had enough cash flow to get and pay back these loans, and so provide early investors an avenue to exit. “We started taking out big loans in order to do leveraged buyouts on early investors,” Barrett explained.

Misunderstandings aside, there was a mismatch between Expensify’s time frame and the cycles of VC funds that needed to give their limited partners returns. “We are not a young company, this is a 13-year overnight success kind of thing,” Barrett noted. While often critical of the VC playbook, he cedes a point in their defense: “Viral business models are challenging because they take time.”

The company’s confidential filing for an IPO is set to complete what the buybacks couldn’t, and it appears to be why the company wanted to file in the first place. “So that [remaining investors including] OpenView Venture Partners, NOMO Ventures and super angel Bobby Lent’s firm Hillsven can cash out,” Insider reported in January of this year.

Metrics money can’t buy

In retrospect, Barrett sees the buybacks as “really good use of money,” especially compared to other spending options. “I was so glad that we spent it on buybacks versus on advertising or whatever, because there’s no reason to believe that would have worked.”

Hearing that statement would probably cause a marketer to choke on their drink, but Expensify had by now learned that its growth doesn’t depend on marketing dollars, and its cost of customer acquisition is not a variable it can play with on a whim.

“That’s always a challenging discussion to get people to try to understand,” Schaffer says. “They say, ‘Well, you spent X millions of dollars, I want you to spend two times more to get two times growth.’ And we say, ‘We’ve tried that, and it just decreases.’”

Expensify therefore spends little on marketing, and when it does, its focus is brand marketing, which brings people into the funnel and increases overall awareness. “And then our product basically converts them,” said Schaffer.

“Up until [ … ] 2019, we did zero traditional outward-bound marketing or demand [generation],” director of marketing Joanie Wang explained in a podcast. “We really focused on experiences closer to the middle of the funnel through events and developing our champions,” she said, referring to the company’s presence at trade shows and its ExpensiCon getaway conferences.

That strategy changed in 2019, because Expensify had ventured into advertising with a full-blown Super Bowl campaign dubbed “You Weren’t Born To Do Expenses,” featuring actor Adam Scott and rapper 2 Chainz “living the life of a baller.” It included a 30-second TV spot as well as a hip-hop music video.

Still from Super Bowl music video. Image Credits: Expensify

The campaign also doubled as a product demo, especially the “Expensify Th!$” music video, where viewers could enter a contest by using the Expensify app to scan receipts of all the over-the-top items shown in the clip. The campaign generated $62 million in earned media and a 1,400% increase in new customers, Wang said.

Its other campaigns garnered a lot of attention, too, such as its its 2011 motorway billboard and its recent video announcing its IPO filing. However, such campaigns were one-off plays.

Expensify focuses on virality for growth, which is why one of its key metrics is its K-factor — “the number of users that are using user-based invites,” according to Schaffer. Like many startups today, it also does advanced cohort analysis, which includes new users in the cohort of the person who originally invited them.

The company also keeps close tabs on conversion to the paid tiers, as well as what it used to call negative revenue churn. “People were looking at us like we were crazy when we were talking about those types of things,” Schaffer says. “I think people call it revenue expansion now, and that those are more accepted.”

Sales team? What sales team?

If you’re looking for Expensify’s sales team and the person running it, prepare for a long-winded answer: “So, Jason [Mills] basically oversees the whole product management flow,” Barrett said, “Which also means that he effectively runs our customer success organization, as well as our sales organization, to the degree that we have it.”

What he means by that last comment is that Expensify doesn’t have traditional outbound or inbound sales. Instead, it worked to make its product as self-serviceable as possible, as that’s what the majority of its customers expect, Mills says.

“In the small business space, people generally just want to try and set this thing up for themselves.” Expensify also supplements this with Guides, who are contractors or staff who answer onboarding questions; a chat-based platform called Concierge; and a forum for its community so customers can help each other.

The support team only spends approximately a third of its time talking to customers, and the system doesn’t exclude other people in the company. “Our very early customer support system was a rotating email system such that everyone was required to talk directly to customers,” Mills recalls. Everyone in the company has “chores,” which is its way of referring to small tasks anyone can take on.

Expensify’s take on product management is also similarly a more open, “democratized process” that anyone at the company can contribute to, Mills explains, as “no one has a monopoly on great ideas. We use a public Slack room that everyone in the company joins by default when they join Expensify.”

People can then share a “What’s Next” post, which requires them to identify a problem and propose a solution in order to start an internal discussion. These ideas need to have a strong case, because the company makes it a point to “respect the status quo,” Mills says. “If that’s not going to work, try to maximize consistency with the present. And if all of those fail, then let’s do something big.” Expensify conceptualizes this philosophy with a simple statement: “Cut, don’t glue.”

Another important tenet at Expensify is the concept of “compounding product management,” wherein product development focuses on pain points that apply to all users, not just a new customer or a small subset. Mills says, “When a company wants us to change the product so dramatically outside of where all our other customers and we believe the market needs a solution, that’s where we effectively are very good at saying goodbye. But It doesn’t happen that much.”

Despite these principles and its focus on SMBs, Expensify has some very big clients, which include public companies. “We grow with the majority of our customers, and that’s the interesting thing about the SMBs,” Mills notes. The company’s “Wall of Fame” includes the likes of Atlassian, GitHub, Stripe and Pinterest. It also can take on new enterprise leads as long as they are fine with the same product as other customers. But if there’s one thing Expensify doesn’t plan to do, it’s going upmarket.

The Amazon Prime of the back office

Expensify doesn’t feel the pressure to get into enterprise sales as a top-down company would, Barrett says. “With a traditional acquisition model, they always just gradually get pulled upmarket, because everyone in the company is motivated to go upmarket. The sales people think, ‘I get a bigger commission check if I close a bigger customer.’ The product managers want to build more exotic functionalities. Everyone’s job is basically about getting the next biggest customer.”

Instead, Expensify is happy to continue prioritizing the SMB market, which Barrett sees as a “much, much bigger opportunity” with fewer challengers. Having seen competitors come and go throughout the years, the company is confident in its market position.

Besides the product and tech stack, its biggest moat is legal — individual account ownership, “which no other enterprise business has,” Barrett says. “It’s basically impossible to reproduce [ … ] unless you’re starting from scratch. But if you’re starting from scratch, there’s no way you can compete with us because it’s a word-of-mouth business model and we have 10 million mouths talking about us.”

But when we talked to Schaffer in February, he described the space as “very noisy,” pointing to Utah-based corporate spend management startup Divvy as “probably the closest to [Expensify’s] offering.”

Divvy’s success may be a good sign for Expensify’s IPO, as Bill.com bought the startup for a whopping $2.5 billion just last month — within weeks of Expensify’s confidential IPO filing. As my colleague Alex Wilhelm noted, the amount was “substantially above the company’s roughly $1.6 billion post-money valuation that Divvy set during its $165 million, January 2021 funding round.”

The fact that Divvy’s buyer is a payments giant is also indicative of the expansion in the space. Expensify added a bill pay feature to its product in 2020, followed by an invoicing feature. These were the first steps in Expensify’s plan to diversify into a “pre-accounting” platform, which Barrett defined as “the system through which financial data is gathered, coded, aggregated, and normalized so as to enable accounting to occur.”

“Our thesis is that [for] the vast majority of the market, this is all they need,” Mills says. This also takes Expensify closer to being what Barrett dubs “the Amazon Prime of the back office” — a single price that will do all of your back-end finances.

Expensify can afford to not charge extra for these new features, because the brand’s popularity compensates for extra costs. And with invoicing and billing being shared between companies, any user becomes “a whole new entry point into our viral business,” Mills explains.

Director of product and customers, Jason Mills. Image Credits: Expensify

There is one new product for which Expensify charges extra, though, but in a typically unique manner. Among the reasons to launch the Expensify Card “was simply to earn interchange [fees] off of each card purchase.” The card itself is free, but if customers can’t or won’t adopt it, they get charged an unbundling fee to make up for lost potential revenue.

Barrett said in an April 2020 post that this pricing policy for the card was to offset the impact of COVID-19 on the business at the time, but that is no longer the case, as the company has recovered and, according to Schaffer, ended 2020 with more revenue than they started.

So additional revenue from interchange fees has now taken a backseat again. “We have great traction on the card and we’re very excited about that, but it’s not a make-or-break for the business,” he added.

Instead, Schaffer says the card has mostly been about UX, as using the card won’t require users to take pictures of receipts. “We can run all of the AI, look at all the company policies and do everything at the moment of the purchase instead of waiting for the receipt to get transcribed and then doing it. So for us, the card was the natural progression on how to make things even better than they already were.”

Schaffer thinks Expensify has a big advantage over other card players as it has a big established base of business spend. However, it faces increasing competition from fast-growing, heavily-funded corporate card and spend management startups such as Ramp and Brex.

But for Expensify, the next big thing is not its card. That privilege goes to Expensify.cash, a financial group chat platform with big ambitions. According to a December 2020 post, the service works like Slack, SMS or WhatsApp, but is optimized for financial conversations.

Still in development, this open-source service appears to be Expensify’s attempt at joining the group of companies that have billions of users, not millions. “There are the Venmos and the PayPals that have hundreds of millions of users, but the only services that have billions of users are chat, whether it’s Facebook, LinkedIn, WhatsApp, things like this. So we feel like chat is the biggest use-case possible, because it’s what connects everyone together,” Barrett told TechCrunch.

Built with a vision

As with everything it does, Expensify set out building Expensify.cash by simply following its core philosophy of compounding upon and building on what it already has. The company has over the years stuck to its strong belief in building for the long term, and you can see it in everything from its tech stack and its growth and retention policies to hiring and business model.

So it’s not hard to imagine this company reframing its core. What appears to work for Expensify is that its team was never in it for the expense reports. They weren’t hired on that basis, and it is not what drives them. “I think that we want to build a giant business using a network-effect business model. We’ve wanted to do that from Day One,” Barrett says.

That approach forced Barrett and his employees to make a number of decisions that may have seemed preposterous because the company was on a path that took it far from what everyone else assumed it was going to do. This included focusing on SMBs, building a highly unusual tech stack optimized for virality and insisting on individual ownership of accounts, all of which paved the way for Expensify.cash.

But those decisions have paid off in the long term in the form of very impressive employee-to-revenue ratios and a profitable business model that’s optimized to scale. Barrett puts it succinctly: “If you want to build a great long-term, sustainable company, you have to do it from the start.”

It is too early to tell how and if Expensify.cash will succeed, but we know one thing for sure: This is not an accident. And if Expensify’s bets so far are anything to go by, we feel this new venture may just go on to become something entirely unexpected and beyond what the rest of us think.

Expensify EC-1 Table of Contents

This EC-1 was serialized starting early May and continuing through early June.

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Culture

- Part 3: Expansion and remote work

- Part 4: Engineering and technology

- Part 5: Business model

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.