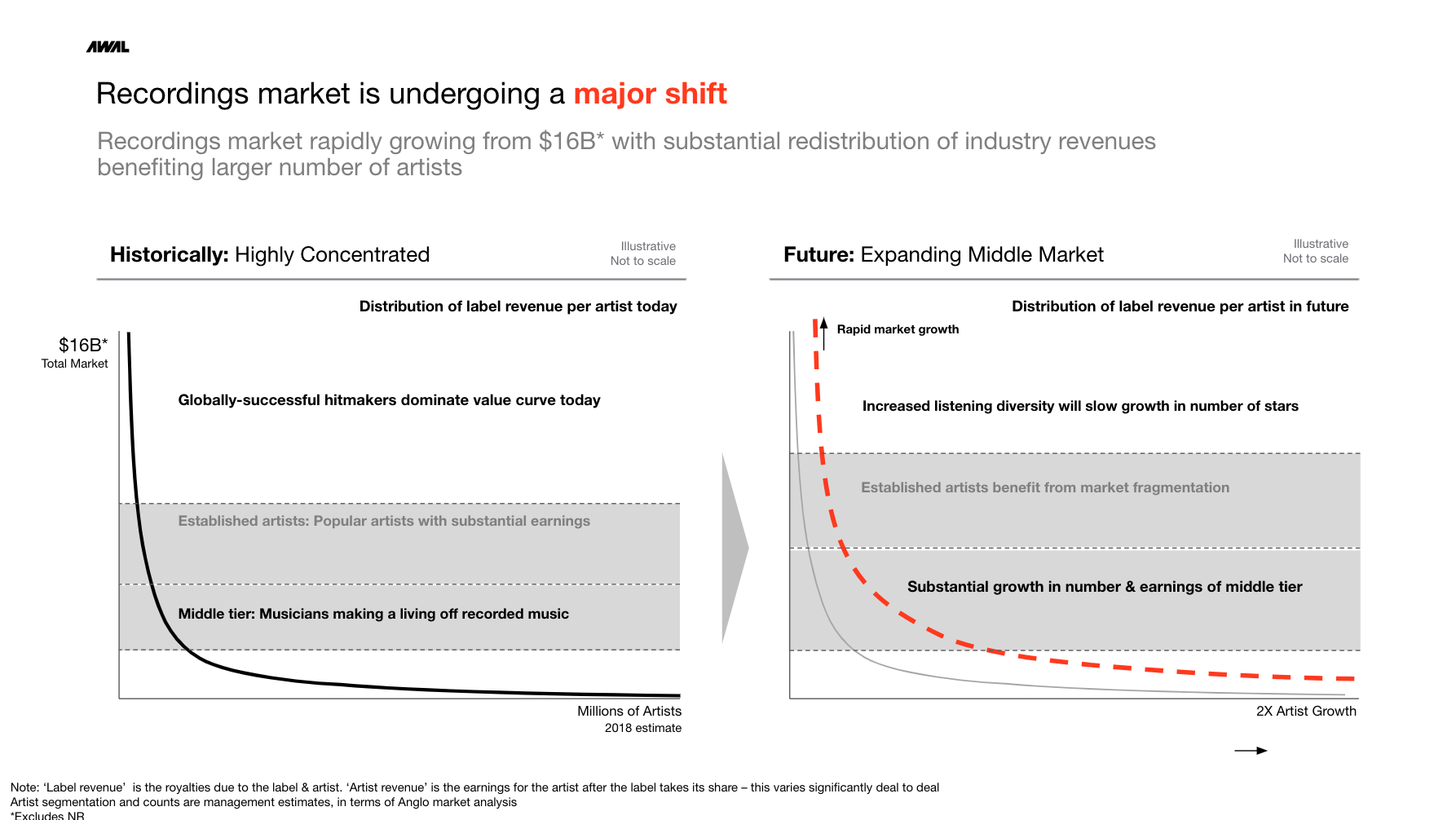

Streaming services have made music ubiquitous, driving more exploration by consumers who don’t have to pay for each song or album individually. Musicians are correspondingly able to find their own niche of fans scattered around the world.

(This is the third installment of our EC-1 series on Kobalt Music Group and changes in the music industry. Read Part I and Part II.)

As Spotify gained rapid adoption in his native Sweden in 2006, Kobalt’s founder & CEO Willard Ahdritz predicted music streaming and the rise of social media would increasingly undercut the gatekeeping power of the major label groups and realign the market to center more on a vast landscape of niche musicians than a handful of traditional superstars.

Both of these predictions have proven directionally true. The question is to what extent and how are industry players actually realigning as a result?

What musicians need in addition to the administrative collection of their royalties (explained in Part II) is a menu of creative services they can tap for support. Kobalt’s AWAL and Kobalt Music Publishing divisions provide such services to recording artists and songwriters, respectively, and do so on purely a services basis (getting paid a commission but not taking ownership of copyrights like traditional labels and publishers do).

Niche middle class vs. Global superstars

The whole music industry is growing substantially due to streaming music’s mainstream penetration in wealthier countries and increased penetration in emerging markets.

As the overall pie is growing, the non-superstar segment of the market is indeed growing faster than the superstar segment, taking over a larger portion of industry royalties.

According to data from BuzzAngle, the top 500 songs in the US in 2018 accounted for 10% of on-demand audio streams — a dramatic decline in market share compared to 2017 when the top 500 songs accounted for 14% of streams. Stepping back, the top 50,000 songs made up 73.2% of all US streams in 2017 but that declined to 70.5% in 2018.

The three major label groups — Universal Music Group, Sony Music, and Warner Music Group — have 60% market share in recorded music collectively, and their whole business model is producing global superstars. Not unlike a VC, they invest in a portfolio of talent with the goal that several become outlier wins. There are many smaller labels outside the majors (called the indies) who strike similar deals but usually with smaller investments in smaller artists.

As another sign that consumers’ listening is becoming less concentrated on the top hits and more inclusive of small artists, self-released recording artists (those with no record label at all) reached 3% market share of recordings in 2018 — that’s a small portion but at $643 million it is 35% year-over-year growth for the segment.

Statistically, music is becoming slightly less of a hits-driven business.

Kobalt’s internal prediction is that there were over 15,000 artists in the worldwide English-language market who earned tens of thousands of dollars from their recorded music catalogs in 2018 and they expect that to soar to over 60,000 in 5 to 10 years. Kobalt estimates over 5,000 artists earned hundreds of thousands of dollars in 2018 and expect that segment to double to over 10,000 in the same 5 to 10 year timeframe.

Image via Kobalt

The re-organization of artist services

There are four categories of recording artists now:

- Superstars – global mass-market brands central in pop culture, filling arenas and stadiums, and generating 8- and 9-figures in annual revenue.

- Niche stars – recording artists who’ve secured a large, devoted fan base within a given niche sound. They tour around the world in small and midsize venues and earn 6-figures, sometimes 7-figures, in revenue.

- The middle class – recording artists who’ve found a core niche of tens of thousands or more fans and can make music their profession due to annual revenue in the tens of thousands.

- The long tail – everyone else releasing music, generating little to no royalties. Kobalt isn’t active in this segment.

Musicians transition between these segments based on their career’s traction, requiring different types of support at each stage. The industry is changing to serve each category better.

Going AWAL

A growing crop of companies have risen to service a) the middle class who are talented but too small commercially for the major labels and b) the niche stars who have chosen to turn down labels (or been dropped by them). These are the territories Kobalt wants to dominate through its label services division, AWAL.

According to AWAL CEO Lonny Olinick, the business is on track to grow 80% this year (with the fiscal year ending in June). In March 2018, Kobalt publicly committed to spending $150 million on growing AWAL into the leading label services option on the market.

“If I look at every single one of the segments we operate in, I think there’s a billion-dollar opportunity in each,” said Olinick when we spoke at AWAL’s Los Angeles headquarters. The segments he was referring to were AWAL, AWAL Plus, and AWAL Recordings — the three tiers of service offerings ranging from basic distribution and analytics (AWAL) to an account manager and marketing budget (AWAL Plus) to a full suite of services on par with those of a label (AWAL Recordings).

At its base level, AWAL offers distribution without an upfront charge, handling of royalty payments, a dashboard of analytics to dig into who your fans are and where your music is getting played, and inclusion of your songs in the pool of songs their team is constantly pitching to streaming services for inclusion on popular playlists.

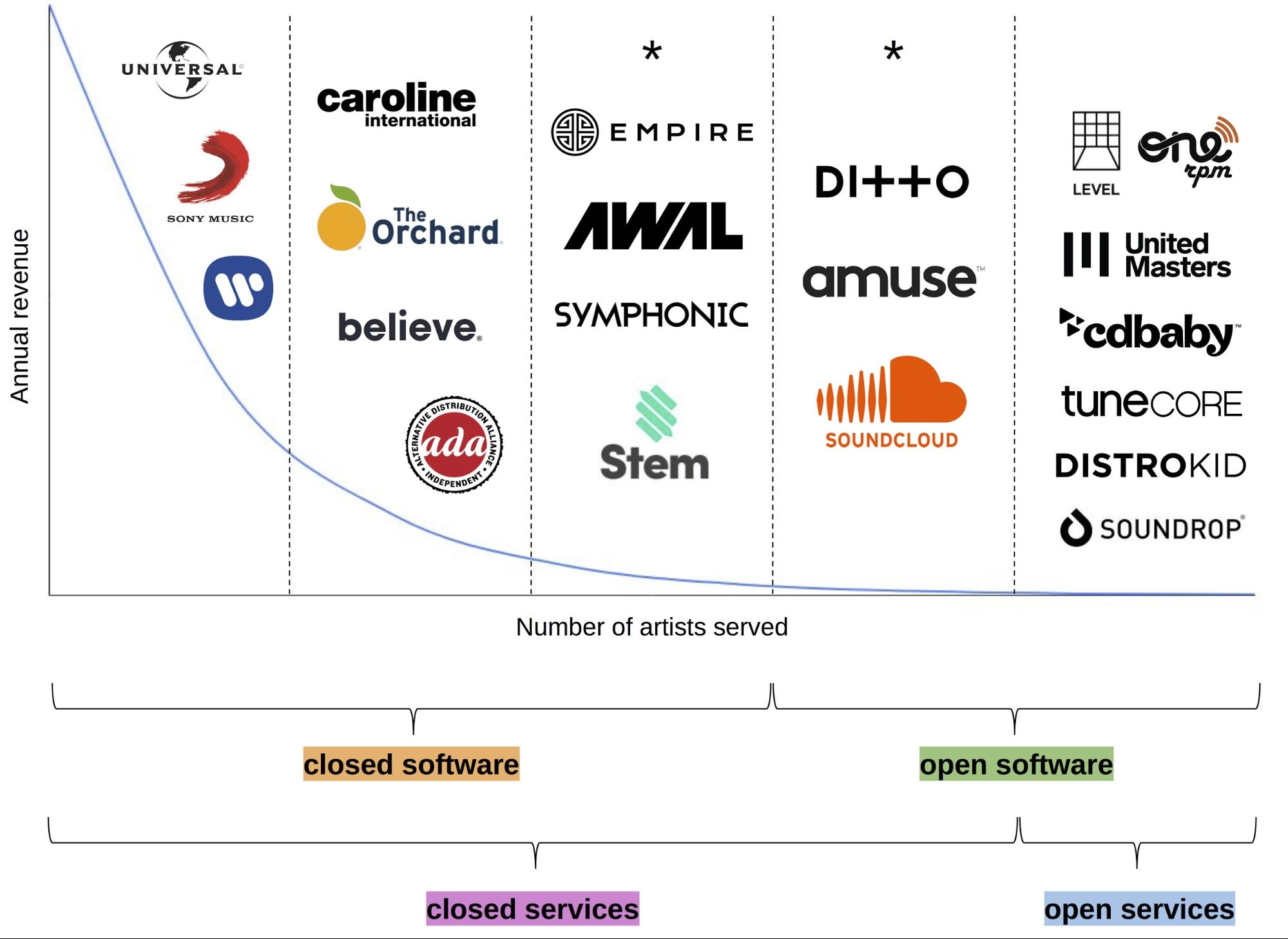

Music industry journalist Cherie Hu created the graphic below to map different services by the category of recording artist they are built to work with (by artist revenue size). The base tier of AWAL is a scalable solution but only for approved artists since it makes money through a revenue share and the long tail of artists don’t generate worthwhile revenue.

With AWAL Plus and especially AWAL Recordings, the company is expanding upmarket to support niche stars and rising stars among the middle class with a more hands-on, full service offering closer to what the major labels do.

Kobalt is differentiated from its competitors here with a services infrastructure that’s global and by leveraging its KTech operating system (discussed in Parts I and II) to be smarter about analyzing earning potential, offering advances, and providing analytics to efficiently target potential fans. It’s also the bundled solution, handling royalty collections and a full stack of creative services for both recording artists and songwriters (who are often the same person).

The middle class of recording artists

If you’re a middle-class artist who hasn’t been offered a major label deal and perhaps doesn’t want one, you can take the default do-it-yourself (DIY) path of an unsigned artist or you may sign with an indie label. Indie labels want you to sign away your copyrights and most of your royalties for years, just like the majors, but without the ability of a major to develop you into a superstar for that trade-off to be worth it.

As a middle-class DIY artist, it’s on you to get your songs distributed across all the global music streaming and download services (referred to as DSPs) and promote yourself to find new fans.

Several distributors are open to all and charge for song submissions upfront so they grow on a “quantity over quality” basis that fits the long tail (and is used by many in the middle class).

- DistroKid (part-owned by Spotify) and Ditto charge $19-20 per year, as does Warner Music Group’s Level Music service (after the first two uploaded songs, which are free).

- TuneCore and CD Baby both charge $10 per single and $30 per album (though CD Baby adds a 9% royalty fee as well).

- Record Union charges $15 per single and $25 per album whereas Universal Music Group’s SpinnUp charges $10 and $40, respectively.

Simple distribution is commoditized. The increasingly crowded landscape of distributors are differentiating with minor differences in pricing structure and analytics and by offering extra tools and creative services to advance your career.

AWAL’s basic tier

AWAL operates on a commission model, earning a cut when royalties eventually come in. It needs to be exclusive in order to limit clients to those with a chance of generating revenue and to earn trust from playlist curators that the music they pitch has been vetted.

Kobalt’s CTO Rian Liebenberg says AWAL blocks 85% of submissions. The acceptance of an artist is partly automated (based on social media and streaming metrics) and partly human evaluation. They receive a couple thousand applicants per month.

AWAL Plus and recordings

The AWAL team monitors the performance of its clients’ songs and social followings (and evaluates the abilities of a client’s manager). Those with the more commercial potential are offered an upgrade into the AWAL Plus tier of service. This involves hands-on marketing support, the availability of cash advances, and a dedicated account manager — for higher commission rate.

A new talent pipeline

AWAL offers the middle class artist a financially-aligned way to distribute their music — AWAL only gets paid when they do — and the opportunity to earn their way into a higher tier of support, all while retaining their own copyrights and the majority of their royalty income. Most AWAL artists remain in the entry level tier without any hands-on services aside from inclusion in playlist pitching; their goal is generally to qualify for AWAL Plus to have the option of using those services though. For some, AWAL is just the best fit for the early stage of their career and they remain intent on securing a traditional record deal.

Competition over rising DIY talent

AWAL has competition in combining scaled distribution with hands-on services for select clients.

- Symphonic offers distribution, marketing tools, playlist pitching, and a customer support line for 15% commission plus sync licensing, publishing administration, custom marketing campaigns for more.

- Stem — a startup that has raised over $12 million from Upfront Ventures, TPG’s Evolution Media, and others — recently pivoted into direct competition with AWAL Plus, casting the majority of users off its platform and focusing on playlist pitching, marketing strategy, and a dedicated account manager for those who remain (with a 10% commission).

- The new Swedish record label Amuse offers free distribution as a data play to identify new artists to sign to flexible recording contracts (that the artist can end at any time to take a traditional record deal).

- Believe, Caroline (owned by Universal), Ingrooves (recently acquired by Universal), ADA (owned by Warner), and The Orchard (owned by Sony) compete with AWAL Plus and Recordings at the upper end of the market as large label services firms supporting a curated roster of unsigned artists.

Good for artists, tough for business

The growth in label services for the DIY middle class and the competition between companies is wonderful for the artists since it gives them options and leads to more favorable commission rates. This makes the tough to compete in as a distribution and label services business, however. Especially as a VC-backed company with investors looking for dramatic growth from a startup into a large company.

It’s not profitable to provide much hands-on support to middle-class artists given their income, so the offering is a scaled solution with light human involvement. Because distribution is a straightforward software process and the services offered are roughly comparable in quality from the perspective of a potential client, the competition will drive profit margins toward zero.

If the whole DIY market was $643 million last year and distributors with added services like AWAL, Symphonic, and Stem are taking 10-20% of royalties as their cut on average, that’s a tiny market of just $64-128 million globally divided between them.

You can’t depend on 1,000 true fans

There’s a famous blog post by Kevin Kelly about online creators just needing to find their “1,000 true fans” online willing to pay a few dollars each month in order to make a living at their craft.

The structure in which the leading streaming services (aside from Deezer) attribute royalties hinders this from becoming reality in music, however (at least with regard to earnings derived from the content created). Apple Music, Spotify, and others calculate royalties by market share of streams on the platform overall (in each country) rather than the proportional share of each user’s streams. Roughly $7 of a monthly $10 Spotify subscription is paid out in royalties; if I exclusively listen to one niche artist I’m obsessed with, that $7 doesn’t go towards my favorite artist’s songs.

This is a structural advantage for broadly popular artists who large masses of people listen to lightly and a disadvantage for niche artists reliant on a small base of dedicated fans who is years past would have bought physical albums or digital downloads for which all royalties flowed back to them and their collaborators.

Growth at the expense of labels

The big opportunity here is dramatic market expansion by driving more musicians at the upper end of the middle class earning profile to leave their labels at the end of their contract or turn down labels in the first place, choosing the DIY route instead. That larger market of higher-income musicians would allow for more differentiation between competitors through hands-on service offerings and more growth potential for their businesses.

The major labels have been moving upmarket on average, waiting for artists to develop more before signing them (although they are still signing more artists than they used to given the sheer growth in artists finding traction through streaming). AWAL Plus and AWAL Recordings fill the gap and, ideally for Kobalt, cause more musicians to turn down record deals once they’re offered since the vast majority of label clients don’t become superstars (so have given away their copyrights and most of their royalties without the expected pay-off).

Superstar recording artists

Despite the opportunity digital distribution and social media unlocked in building a fanbase on one’s own, the major labels remain the path to superstardom. They are firmly entrenched businesses that have seen revenues grow and valuations soar as a result of streaming gaining mainstream adoption.

The majors can pay the largest advances and can invest many millions of dollars into a marketing campaign. They have long-standing worldwide relationships with every type of promotional partner from radio stations to popular TV morning and late-night shows to brand collaborators like Coca Cola and Visa. Plus, there’s a deep history of favor-trading (and punishment for disloyalty) that keeps many of these relationships allied with the majors. This is a dramatically larger infrastructure to build than what AWAL or any of its direct competitors have.

The major label system has a long track record of delivering stardom — nearly every major star in music for decades has operated within it. Non-label alternatives, AWAL included, have yet to demonstrate a repeatable track record of creating superstars.

For many ambitious artists, achieving the dream of fame is more important than retaining copyright ownership or other preferred terms — they can worry about those issues when they are rich and famous. Once you’re a superstar, you can generate tens of millions of dollars in personal income through touring, sponsorship deals, launching your own consumer brand, etc.

Artists usually sign with major labels believing they will be the breakout success, just like startups raise from VCs assuming they will be a winner in the portfolio — even though the odds are against that.

Down one path you have labels who have successfully promoted everyone from Elvis to Madonna to Beyonce to Drake, and down the other you have newcomers with little to no track record of creating superstars telling you they’ll give you better deal terms.

A consistent takeaway from my interviews with talent managers across several genres is that few musicians are interested in the business side of their career anyway. They are heavily influenced by the perception of what’s cool (getting a big record deal is still cool) and they’re not modeling out their expected future earnings based on different deal terms.

While their managers should make a thoughtful long-term analysis of the best decision, they have similar bias for prestigious deals and — since they get paid in commission and can be fired at any time a deal — a bigger short-term cash advance is safer for them personally than the DIY route.

In addition to dominating influence over radio — which is still plagued by pay-to-play schemes — the major labels meaningfully influence the curated playlists on top DSPs like Spotify, which have a relationship-based pitching process similar to radio.

The DSPs are dependent on Universal, Sony, and Warner since they own most of the popular music that consumers want to listen to. For just one of the three majors to pull out of a streaming service would cripple it with a giant lack of songs in its library. That provides the majors with unofficial sway among DSPs.

Niche Stars

There’s a growing field of musicians between the middle class and the superstars, and AWAL’s infrastructure is attractive to them as an alternative to traditional labels, at least temporarily.

Major labels’ move downstream, awaiting more traction by artists, keeps rising talent among the middle class tier of professional recording artists on the DIY path for longer. They become clients of services like AWAL Plus and then ideal customers for the hands-on label services offerings of AWAL Recordings, The Orchard, Caroline, and others.

These artists can drive hundreds of thousands or even millions of dollars in top-line earnings by finding a large fan following in a given niche of music. They are the leading talent in a specific sound that millions of people worldwide enjoy. In many cases, that sound doesn’t have broad-based mainstream appeal so there’s a ceiling limiting a jump in global stardom. In other instances, there is the potential to make the leap up to superstar but it’s fiercely competitive and requires a large marketing investment both to get there and to remain there for more than one hit song.

AWAL Recordings handles traditional physical album distribution and radio promotion, but it’s appealing to artists who want to optimize for what works and are comfortable if that means not putting their face on billboards.

AWAL’s Olinick told me he has 150 employees dedicated to promotion efforts, including 15 people just working on US radio promotion. AWAL also struck a partnership with NetEase — the $35 billion games and music streaming giant based in Guangzhou — for distribution and promotion in China.

Being a niche star signed to a label is tough because most of the economics go to the label and you are beholden to the marketing decisions as the copyright owners. As a niche star with AWAL Recordings, you retain decision making power and most of the economics, and since you own your copyrights you have the option to sell them in the future (like an entrepreneur exiting their startup).

Majors want a piece of the action

While AWAL is expanding into label territory, the major labels are also expanding their own label services offerings for unsigned musicians ( Caroline, Ingrooves, ADA, and The Orchard). The majors want of piece of this growing DIY market and benefit from undermining potential competition from Kobalt and others. There can be a lot of politics in a major’s decision of who to provide such services to and the strategy to employ, however. The label services clients sit firmly behind the label’s main roster in priority.

AWAL, the big independent

AWAL stands out for its independence here — it can represent its clients first, competing head-on against major label artists for promotional opportunities and consumer attention. AWAL stands out among the independent options through its size and global infrastructure. It’s the best independent alternative to a major label in its ability to promote artists globally.

Kobalt’s investment in aggressively upgrading AWAL to compete with AWAL Recordings is fairly recent. With low hundreds of clients currently and an estimate that the market for these niche stars in just the English language will grow to 10,000 soon, AWAL Recordings has a path to grow 10x while remaining just one of several players in the market.

Indie labels as frenemies

The AWAL Recordings tier of services undercuts indie labels the most, and the growth of DIY niche stars and middle-class musicians in the market is apt to come at the expense of the indies.

If an artist isn’t getting a contract with one of the majors best resourced to promote them globally, why settle for the same terms — giving away copyrights and most royalties — for a smaller, more limited version? It makes more sense to partner with AWAL instead.

AWAL has a long roster of indie labels as B2B clients paying to use AWAL’s services to augment their own (the majors do the same thing). It’s bringing Kobalt short-term revenue but ultimately, for it to grow, the company needs to shift more of the indie label market into the DIY camp.

Given their firm grip on the copyrights and royalties, indie labels will take on more financial risk in signing a new artist than AWAL will, especially in terms of paying an advance before a track record is shown. So there will remain a long-term role for these indie labels in taking the riskiest “seed stage” bets, to make a VC comparison, but the terms of a deal won’t make sense for most artists if they can qualify for AWAL Plus or Recordings and are willing to put in extra work promoting themselves.

A superstar brand halo

Thus far, Lauv is AWAL Recordings’ biggest success story with over 3 billion streams of his songs on Spotify and Apple Music. If AWAL succeeds at advancing a niche star into a global superstar and retaining them as a client—be it Lauv or someone else — it will be as a critical proof point for musicians to view AWAL as a credible path to the top. If it can pull that off multiple times, it would cause a shift downstream among ambitious niche stars and middle-class musicians becoming more comfortable with AWAL as an alternative to a record deals.

On this basis, it’s more important for Kobalt to invest the resources in making that happen than it is for them to profit off their efforts for that one client. The major labels will remain specialists in producing global superstars, but they may keep moving downstream if enough artists want to use DIY solutions like AWAL Recordings to build their careers and only consider a record deal when they’ve the negotiating position to get it on reasonable terms.

Continue by reading Part IV of the Kobalt EC-1. (Make sure to read Part I and Part II if you haven’t already.)

Kobalt EC-1 Table of Contents

- Part 1: Founding Story and Overview

- Part 2: The business of recording royalties

- Part 3: Building a new economic class of musicians

- Part 4: Competitive landscape

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.