Backed by over $200 million in VC funding, Kobalt is changing the way the music industry does business and putting more money into musicians’ pockets in the process.

In Part I of this series, I walked through the company’s founding story and its overall structure. There are two core theses that Kobalt bet on: 1) that the shift to digital music could transform the way royalties are tracked and paid, and 2) that music streaming will empower a growing middle class of DIY musicians who find success across countless niches.

This article focuses on the complex way royalties flow through the industry and how Kobalt is restructuring that process (while Part III will focus on music’s middle class). The music industry runs on copyright administration and royalty collections. If the system breaks — if people lose track of where songs are being played and who is owed how much in royalties — everything halts.

Kobalt is as much a compliance tech company as it is a music company: it has built a quasi “operating system” to more accurately and quickly handle this using software and a centralized approach to collections, upending a broken, inefficient system so everything can run more smoothly and predictably on top of it. The big question is whether it can maintain its initial lead in doing this, however.

The business of a song

Let’s walk through the journey of a fictional song to understand the many pain points that exist (this is even a simplified version). Two songwriters, Amanda and Ben, had a writing session with a singer named Chloe. They came up with a pop song called “Summer Love” that Chloe wants to include on her upcoming album. They decide to share credit equally. This is a song composition.

When Chloe records her performance of “Summer Love” and puts it on her album, that’s the song recording. Legally these are two separate things: there’s only one composition but it can be recorded countless times by different recording artists. As a result of this legal distinction, the music industry has entirely separate, parallel infrastructure set up to support musicians with songwriting and to support them with recording.

Tracking the use of “Summer Love” around the world and getting paid the royalties from it is a nightmare. The song is available on all streaming platforms and gets played on internet radio services like Pandora. In several countries, it ends up on radio. There are different types of licenses involved in the right to play a song, each with a different royalty structure and collection method.

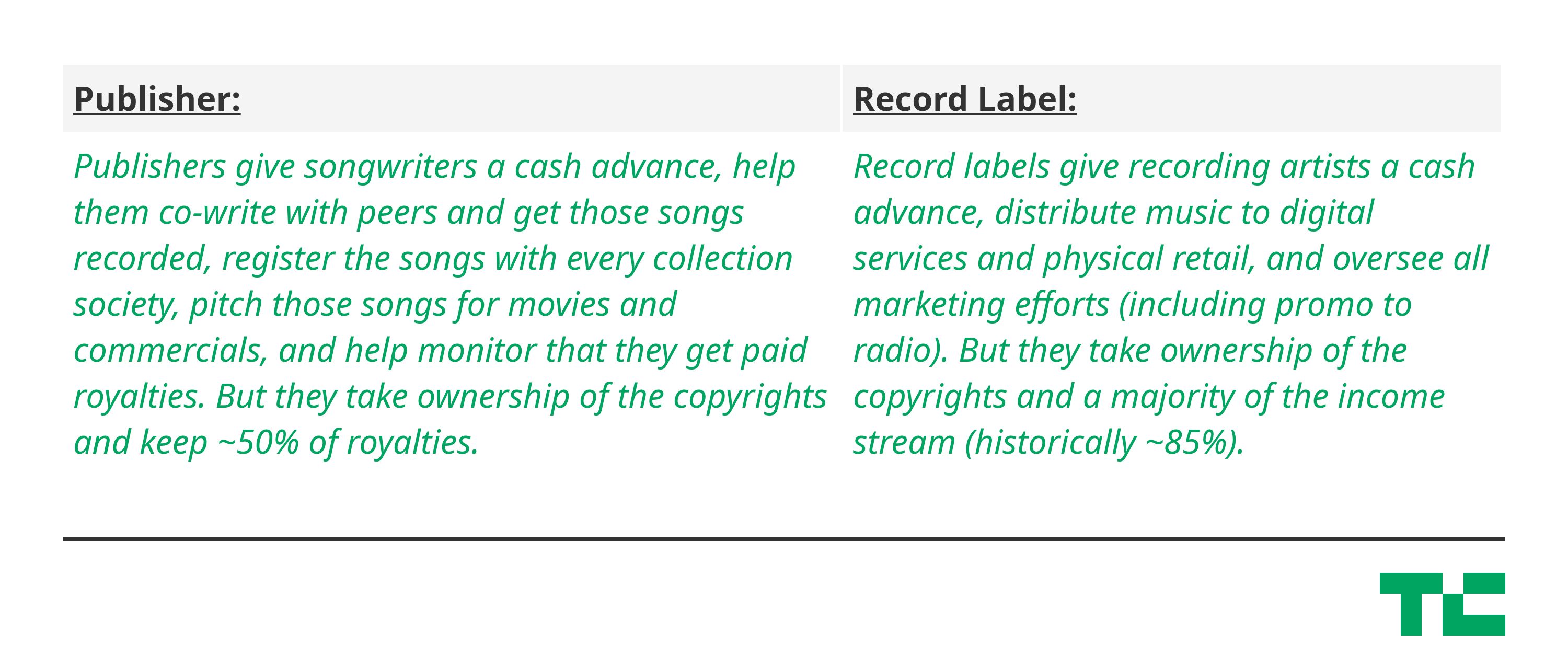

Let’s assume that Amanda, Ben, and Chloe are each signed to a different publisher and that Chloe is also signed to a record label since she’s a recording artist. Here’s a graphic from Part I to remind you what signing to a publisher or a label entails:

Songwriting royalties

For the composition, there are: 1) performance royalties for the public performances like radio plays, internet radio streams, and streams in retail stores; 2) mechanical royalties for sales of CDs, iTunes downloads, and ringtones; and 3) sync royalties for use of the song in TV commercials, films, video games, etc. Streaming services like Spotify and Apple Music trigger both the performance license and mechanical license so they pay both.

I’ve found market size estimates within the music industry vary dramatically but, to get a sense of these royalty types, the distribution of royalties for compositions in 2015 globally was 66% performance, 16% mechanical, and 8% sync based on the calculations of Spotify’s chief economist. By comparison, the trade association of US publishers estimated a breakdown of publishing revenue in the US that year as 56% performance, 18% mechanical, and 20% sync.

Amanda needs a collection society in every country to represent her for royalty collection there. Her publisher and home-country society will handle this administrative work. Many countries just have one monopolistic collection society, others like the US have multiple (ASCAP, BMI, SESAC, and GMR). The collection society gives Spotify, radio stations, and others the blanket rights to use all its music on condition of paying the royalties.

Each collection society brings the money in, figures out how much it owes to who, then transfers Amanda’s royalties to her US collection society, minus a fee. Amanda’s US society takes another fee then pays half of the remaining royalties directly to Amanda and half to her publisher. Her publisher shares some of the royalties it receives with her per the terms of her publishing deal.

Mechanical royalties are similarly paid to rights management agencies (though sometimes they are instead paid to record labels who are supposed to pass them along). In some countries, this is the same society that collects performance royalties — as with SACEM in France — and in other countries this is handled by entirely different organizations — as with the Harry Fox Agency in the US. Often there is only one collector designed as the official mechanical collections body by the government.

This inconsistency results in confusion and often unclaimed royalties for songwriters like Amanda — her collection society sends her some but not all mechanical royalties from around the world. Whether her portion of the publishing royalties is sent directly to her — like the songwriter half of royalties is — or is passed through her publisher is also inconsistent.

Some societies payout monthly, others every six months, and a few only annually (even though Spotify and most digital music services — termed DSPs — pay them monthly.) Historically, publishers would also only pay out royalties to their clients every six months. Altogether, it’s common for a songwriter to not see the money from a performance of their song until 18 or 24 months later.

Recording royalties

As the recording artist, Chloe is also owed royalties for the recording-related licenses of “Summer Love” (as is her record label). Record labels license their recordings to streaming services and the streaming services pay them directly for the mechanical license.

Recording artists’ equivalent to songwriter performance royalties — for radio plays, internet radio streams, etc. — are called neighboring rights royalties. Collection societies collect neighboring rights royalties for “Summer Love” in each country. After taking a fee, they then send half to Chloe’s record label and half to Chloe directly.

Missing money

Piracy aside, Amanda, Ben, and Chloe don’t collect all the money they are owed for use of “Summer Love” around the world.

Since the tracking of copyright information and royalties is so decentralized and collection societies (and publishers and labels) don’t have the technology infrastructure to coordinate all the data points, mistakes are often made. If in the process of data entry, an employee at Amanda’s collection society in Brazil accidentally writes the song title as “Summer Luv” or misspells Amanda’s last name, Amanda could miss out on the royalties due from that country.

Sometimes these situations are resolved but otherwise unclaimed royalties are pooled after three years and paid out to publishers (or labels, depending on the royalty type) based on these companies’ market share in the country.

That is a misalignment of incentives. Large publishers and labels get paid money they weren’t entitled to as a result of clerical errors and ignorance of small musicians who don’t know all the registrations they need to file; the collection societies have money in their accounts that no one is holding them accountable for. It’s tough to push for aggressive improvements in the system when you benefit financially from its complications.

Collection societies have historically been black boxes where little data is shared and there’s much room for misappropriation of funds. Amanda just knows she got $100 in royalty money from Australia and that’s it. Historically, publishers haven’t shared much data with their clients either.

The Spanish and Greek collection societies are embroiled in ongoing fraud scandals and such scandals are not uncommon. Based on the conversations I’ve had, it seems standard among music industry professionals to believe foreign collection societies take a lot more money than they are supposed to.

Data disorganization

Just like startups keep their cap tables private to avoid sharing who owns how much equity, music professionals keep the ownership details of songs private. There’s no public, universal database to clarify ownership details.

The rise of online music streaming created orders of magnitude more data for each party in the process to manage. It is no longer just physical album sales and digital downloads from iTunes — every time a song is streamed across a landscape of different digital services, it is a theoretical transaction that needs to be accounted for. One chart-topping pop hit will have tens of billions of transactions associated with it in a year, further multiplied by all the writers, publishers, and recording artists attached to it. And with online distribution of music, there are far more songs released every year. Spotify averages 280,000 new uploads per week.

Every music industry professional I’ve asked about collection societies (who didn’t work at one) said they are laggards in technology. Some like Canada’s SOCAN are more progressive than others, and there’s been a growing realization among them that they should license software from others rather than each building their own in-house.

How Kobalt handles copyrights & collections

The rise of music streaming as the top music consumption method creates the opportunity to centralize the tracking of copyrights and the payment of royalties in a more transparent, time-efficient manner. The internet is global, not siloed by country (for the most part).

Kobalt’s software platform, KTech, tracks this web of relationships for every song it is responsible for. It directly receives data from nearly all the DSPs and it incorporates data from the societies that collect clients’ offline royalties to provide analytics on song performance and money owed. According to Kobalt CTO Rian Liebenberg, the platform tracked 4 trillion transactions over the last year, up from one trillion three years ago.

Using its KTech software platform, Kobalt handles copyrights and royalties through three of its five divisions:

- Kobalt Music Publishing (KMP), a publisher which focuses primarily on admin deals — just handling ownership tracking and royalty collection for a songwriter and not providing creative services.

- AMRA, a collection society that gathers performance royalties, and sometimes mechanical royalties, globally (except the US) in a centralized manner rather than on a country-by-country basis. Kobalt Music Publishing clients are automatically enrolled in AMRA.

- Kobalt Neighboring Rights (KNR), which acts as the agent of a recording artist overseeing that all their neighboring rights royalties are collected by various societies and agencies around the world

AMRA and KMP provide a vertically-integrated one-stop-shop for handling all of a composition’s tracking and collections. Admin publishing drives the vast majority of Kobalt’s gross earnings as a business. It’s the heart of KMP, which brought in collections of $263 million last year out of $387 million Kobalt collected across its divisions (according to the company’s filing with Companies House).

That is followed by the gross earnings of Kobalt Neighboring Rights (KNR), which handled $69 million in collections in the same period. KNR leverages the infrastructure on behalf of recording artists to hold the neighboring rights collection agencies they are registered with accountable to collect and pay all royalties. It is a cost-efficient path for Kobalt to capture a small percentage of the royalty income of industry superstars like Tove Lo, The Chainsmokers, Dua Lipa, Sam Smith, and Kygo who remain with traditional record labels.

Liebenberg explained in our interview that “time to money” is a leading metric for the business. Getting clients paid more and faster than anyone else. In its earlier years, he explained, “Kobalt was effectively a registration and collection engine as a service to the music industry. It used to be about being the bank of the music industry. Now, it’s basically that banking service plus a whole bunch of insights and analytics.”

One-stop-shop

Regardless of digital transformation within traditional collection societies, their country-level system doesn’t make sense for digital music. Streaming platforms have the data on every single stream of a song across every country they operate in. Breaking that down into streams within each country then looping it through a local society and then the recipient’s home country society is archaic.

One globally-active society speeds up accuracy and time-to-payment, and Kobalt’s predictive analytics on the data lets it advance cash to musicians without taking much risk since it can see the amount and timeline of future royalties due.

Offline royalty collection still requires local infrastructure so traditional societies will still play a role (especially since some have a government-backed monopoly in their country). Kobalt’s AMRA focuses on digital collections and partners with them as needed in certain countries for offline royalty collection. With offline performance and mechanical royalty collection a shrinking portion of the market and streaming’s growing dominance, it’s unnecessary for Kobalt to invest in building all the local infrastructure for it.

Better data, more money

A technology-first approach to tracking royalties, with highly organized, complex databases and analysis of DSPs’ data, enables Kobalt to identity royalties owed that may otherwise have gone unclaimed. From clips used in YouTube videos to typos in data-entry of traditional collection societies, hundreds of millions of dollars in royalties owed to songwriters are left on the table each year. Kobalt is also sharing a lot of data directly with its clients, setting an industry standard in transparency.

Mark Beaven, founder of talent management firm Advanced Alternative Media, shared with me that he has had Kobalt’s work for his clients who use Kobalt Music Publishing audited and out of over $100 million in earnings less than 1% needed further review. “Usually one could find 5%, 10%, or even 30%,” he explained in reference to audits he and his peers in the industry have done on numerous publishers over the years.

B2B

Independent publishers (meaning not part of Sony/ATV, Universal, and Warner Chappell) outsource admin publishing work to KMP so they can focus on creative services. Kobalt has over 600 B2B clients, who drove roughly half of Kobalt’s publishing revenue last year, according to a company representative.

Independent publishers comprise 41% of the global publishing market. They are more hands-on with their musicians and take on more financial risk (than KMP does with its clients) by signing them and paying them upfront advances early in their careers.

The major publishers could benefit from outsourcing administration to Kobalt Music Publishing like many small publishers do, or at the least using AMRA for collection of digital performance royalties instead of relying on the country-by-country society system. They view Kobalt as too much of a competitor to do this, however, and rightly so (as I’ll explain in Part III).

Becoming the market leader

A monopolistic victory for Kobalt in the copyright tracking and royalty collection space would entail it handling admin for the entire indie publishing market while representing all recording artists (indie and major) in overseeing the collection of their neighboring rights royalties.

Due to competition and regulation, Kobalt can’t attain such a monopoly, but it could capture a large slice of this market if it continues to leverage a combination of software and administrative efficiencies to discover more unclaimed royalties and get royalties paid faster relative to traditional collection societies and other publishers.

The key question is whether Kobalt will capture a long-term leadership position by accelerating the digital transformation of copyrights management or whether it is merely the leader during stage 1.0 of the industry’s digital transformation. Could the incumbents catch up, and might a more radical shift in copyrights management uncut both Kobalt and the incumbents?

Reform among incumbents not enough

Competition from Kobalt through AMRA and KMP has forced collection societies and major publishers, respectively, to invest in technology infrastructure, share more data, and pass along royalties faster.

Top publisher Sony/ATV, for example, has rolled out a guarantee that it will pay its songwriters within the next pay cycle (by partnering with Lyric Financial) and just one month ago announced no-fee advanced payment of royalties. This speed in payment is easier for Sony/ATV given the cash flow from its large catalog, enabling it to advance cash for longer than Kobalt can before it actually collects. Not all three major publishers have made the same progress, however.

Both collection societies and traditional publishers are services businesses who have expanded IT departments to handle their technology needs; there’s a fundamental difference in culture and executive team focus between them and a technology-first company than has added services to leverage its product like Kobalt.

While incumbents will make strides and the major publisher clients will use the tools their publisher provides, the current landscape of societies and publishers is less threatening to Kobalt’s ambitions than newer entrants. Third-party technology vendors could gradually help them gain a tighter grasp on digital collections though.

Peer competition

Kobalt has several digital-native competitors in copyright tracking and collections, like Songtrust (which provides admin publishing and neighboring rights collection) and Tunecore (a distributor for recording artists that also offers admin publishing).

However, they depend on the traditional collection society system for performance rights royalties rather than bypassing it. Through vertical integration of a collection society and publisher, Kobalt can offer more transparency and has the potential to offer lower combined fees, since there aren’t two (or more) separate parties each taking a cut to finance wholly separate operations.

Kobalt is the only alternative to the traditional collection system for songwriters when it comes to digital royalties, and it’s the only independent entity with the global infrastructure to keep tabs on all DSPs and collection societies for its admin publishing and neighboring rights clients.

Disintermediation

It is in the interests of DSPs and of musicians (and their publisher/label representatives) to disintermediate the collections middlemen. Both sides would financially benefit if there was one universal database — or blockchain protocol — for tracking copyright ownership information and streams of songs on each DSP and sending the correct amount of money back to each party with ownership in a song.

Since unclaimed royalties are still claimed by collections societies, DSPs don’t benefit from unclaimed royalties —inefficiencies in the copyright system are just headaches and potential legal liabilities.

Kobalt investor and board member Tim Bunting of Balderton Capital told me that back when iTunes dominated (legal) digital music — he feared Apple would use its monopolistic power to force the industry onto one solution of its own. “Apple had owned the whole ecosystem until that point,” he said, “We were afraid Apple would build its own royalty platform.”

DSPs have not collaborated to build such a solution collectively or adopt one database as their exclusive partner. They did support the Music Modernization Act (MMA) in the US, however, which mandated the creation of a universal database of copyright information called the Mechanical Licensing Collective for the purpose of mechanical royalties payment. The trade group of US major publishers is leading the project.

Some DSPs are sharing more data directly with labels/publishers and their musicians. Spotify Publishing Analytics is a portal launched in 2018 to give publishers access to all the global data Spotify has about its clients’ music with insights. Direct access to the data helps in holding collection agencies accountable for accurate payment; it also makes the analytics that Kobalt provides to its clients less unique.

A role regardless

It’s unclear how much Kobalt will maintain a lead in copyright tracking given the numerous initiatives in the industry to better account for this data. In any scenario, musicians and their publishers are focused on creative work and will still want someone else to check that all registrations are accurate, that mistakes haven’t resulted in unclaimed royalties, and that all offline royalties are being collected by societies in each country. Kobalt’s role as a leading admin publisher would remain, and its AMRA collections society remains distinct as the leader in the centralized collection of performance royalties, at least for now.

Collective action by stakeholders across the music industry to address the “data disorganization” problem is occurring — with the Mechanical Licensing Collective as the first step — because it is in the interests of DSPs whose control of distribution gives them influence to push for changes. Kobalt’s advantage in tracking copyrights may become less distinct, not more distinct, in response, although that requires organizations already struggling to stay ahead of the software curve will be able to create a robust solution when working together.

Kobalt is a lot more than just its tech platforms and collections, however. The combination of these with its portfolio of services provide a more distinct and defensible position within the music industry. We’ll explore that critical side of the business in Part III.

Kobalt EC-1 Table of Contents

- Part 1: Founding Story and Overview

- Part 2: The business of recording royalties

- Part 3: Building a new economic class of musicians

- Part 4: Competitive landscape

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.