We’ve captured much of Niantic’s ongoing story in the first three parts of our EC-1, from its beginnings as an “entrepreneurial lab” within Google, to its spin-out as an independent company and the launch of Pokémon GO, to its ongoing focus on becoming a platform for others to build augmented reality products upon.

It’s not an origin story that serves as an easily replicable blueprint — but if we zoom out a bit, what’s to be learned?

A few key themes stuck with me as I researched Niantic’s story so far. Some of them – like the challenges involved with moving millions of users around the real world – are unique to this new augmented reality that Niantic is helping to create. Others – like that scaling is damned hard – are well-understood startup norms, but interesting to see from the perspective of an experienced team dealing with a product launch that went from zero to 100 real quick.

- Build on top of what works best

- AR alone doesn’t make a hit game

- Ship the MVP, but have the roadmap ready

- Scaling is hard, even when you’ve done it before

- As your userbase grows, so do your responsibilities

- Visual designs can have growing pains too

- Social features can be useful for more than just growth

- Get users rolling as fast as possible

- Communication keeps users happy

The reading time for this article is 21 minutes (5,125 words).

Build on top of what works best

Everything Niantic has built so far is an evolution of what the team had built before it. Each major step on Niantic’s path has a clear footprint that precedes it; a chunk of DNA that proved advantageous, and is carried along into the next thing.

Looking back, it’s a cycle we can see play out on repeat: build a thing, identify what works about it, trim the extra bits, then build a new thing from that foundation.

Niantic’s first publicly released product, Field Trip, established the focus on getting the user to move around a map, learning the history of interesting places around them. John Hanke had spent the better part of the last decade running Google’s geo (read: mapping) division, so the focus on maps was a natural fit.

People seemed to like the concept of Field Trip; there was something to this idea of building on top of a map. But building up a database of local points of interest proved tough — as did getting users to return over time. After the first few uses, people weren’t coming back; there just wasn’t any ongoing hook. Once you learned what’s around you, why open the app?

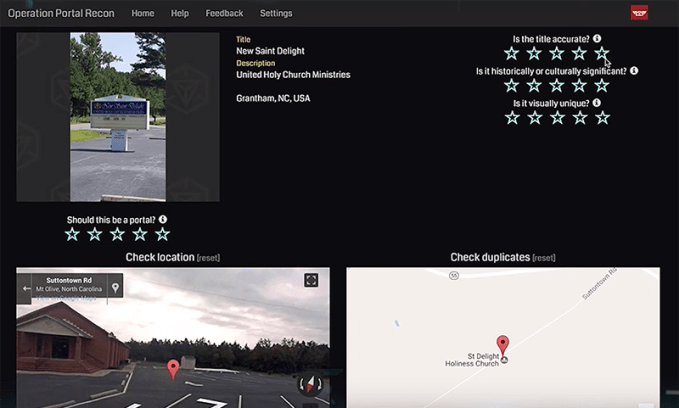

So Niantic took what worked and reimagined it as a game: Ingress. The very underlying core (a map, a database of real-world locations) is Field Trip, but with a truckload of sci-fi lore and cooperative gameplay mechanics piled on top. The local history stuff shifted into the background a bit, but their associated points of interest would now act as crucial in-game hotspots. Meanwhile, Niantic found a way to let players help build up this database of interesting locations much faster than the company could ever build alone, allowing high level players (those less likely to try to cheat, or submit bad data) to submit potential places to expand their local gameboard.

Ingress has a dedicated following, but it’s never had a huge one. Players seemed to like the idea of real-world places doubling as in-game locations… but without an established IP to spark the fire, it’s proven tough to draw in an audience. And for many of those that have checked Ingress out, the game’s complicated mechanics tend to be their own hurdle. Lots of players drop out during the tutorial phase alone.

So they boiled Ingress down to the ingredients they knew worked: a player moving around the map, exploring the world, sometimes working with others for a common goal. They took the tech they’d built for Ingress and mashed it up with a franchise people already knew, tailoring this borrowed universe’s existing concepts to work through this new type of real-world gameplay. They released Pokémon GO, and… well, as anyone who lived in a major city in the summer of 2016 knows, they didn’t have any trouble finding players.

Nearly three years after launch, GO still has a player base that’s spending millions per month — over $75M+ in February of this year, according to estimates from SensorTower. But plenty of people have moved on; might some sort of storyline kept them more interested?

The next step is Harry Potter: Wizards Unite, which builds upon everything they’ve learned with GO. Mega franchise? Check. Collecting things? Check. People clearly like collecting things in GO, so now they’ll be gathering up things from the Wizarding World to help keep them secret. But this time around, there’s a years-long storyline to help drive things forward, with players working together to explain why all of these magical items are appearing in the first place.

Every step leads to the platform — the company’s ultimate goal, the bigger picture beyond making game after game ad infinitum. Now that they’ve put in the work to figure out what goes into products like these, they want others to build on top of it. If AR is going to become a bigger part of our lives, as the company expects to happen as technology progresses, they want to build the layer that powers it, games or otherwise.

Niantic’s “Real World Platform” is an ever-growing collection of tools and datasets that the company has been building, and building with, on each project: the server architecture, the database of real-world points of interest, the social layer, the anti-cheating tools, and more. As they build new tech, like ways to pull off more advanced AR by giving our devices a better understanding of the world in front of them, that’ll all get wrapped in too. If a concept proves viable, it goes into the platform. The more they build up, the stronger the platform gets.

Building on top of what works also means knowing what doesn’t work. Knowing what to trim, be it because it’s not landing the way you expected or because it’s just not worth the time, is its own challenge. But being okay with what doesn’t make it into that next product can be key.

“When we were beta testing [Pokémon GO], I was always comparing it to Ingress.” Says Anne Beuttenmüller, Niantic’s Head of Product Marketing in Europe, the Middle East, and Africa. “I’d test it, and see they’re missing this, or needing to do x, y, and z because it works with Ingress… The personal learning is that you need to let things go and try to do new things, not just repeating things.”

“I remember saying to myself, for example, ‘people need chat!'” she continues. “In Ingress, people can chat. There were lots of things where I was comparing to what Ingress had, and I was saying we should integrate this into Pokémon GO as well. Then I learned: sometimes, you need to just let things go.”

AR alone doesn’t make a hit game

Niantic’s long term vision banks on the idea that augmented reality will become a bigger part of our lives — particularly if, as the company hopes, the next big thing after smartphones is AR glasses.

But they’re quick to admit that AR today isn’t perfect. Even with Pokémon GO, which uses AR to hook people on the whole Pokémon-in-the-real-world concept, it’s sort of just a cute trick. Many people I spoke with at Niantic seem to be fully aware that most players turn off the game’s AR mode once the novelty wears off, opting to swap the game’s camera view of the real world for a static background.

“AR, in and of itself, is not a magic bullet for a hit game,” John Hanke said in a Game Developer Conference keynote in March. “There are some real drawbacks to it”.

Specifically, the ergonomics of using AR on a phone are bad, and battery life takes a hit. No one wants to hold their phone up at eye level for long stretches of time, and letting the camera run tends to eat up battery.

In the same keynote, Hanke outlines a few ways to make AR advantageous today:

- Keep AR sessions short: Niantic tries to build AR experiences that last no longer than 2-3 minutes each. If you’re holding up the phone, it’s not for very long. “You want to think about it as a type of play that happens within a broader game,” says Hanke. “where a lot of the gameplay is not happening in AR mode.”

- Use AR thoughtfully: “We think the right approach here is to design things for AR that really can’t be done outside of AR,” says Hanke. “Try to think of game mechanics where you’re in AR mode, and it’s obvious why you’re there; you’re having an experience you can only realize through AR.”

Niantic continues to explore how to make AR, as it exists today, more worthwhile. It recently introduced an “AR Photo Mode” into Pokémon GO, allowing players to snap photos of the Pokémon they’ve caught with the real world serving as the backdrop. But they see it all as R&D for the future.

“What is happening on handsets today is the warmup. That’s the pregame,” says Hanke. “What’s going to happen with glasses in the future is the real deal.”

Ship the MVP, but have the roadmap ready

A woman holds up her cell phone as she plays the Pokemon Go game in Lafayette Park in front of the White House in Washington, DC, July 12, 2016. (Photo: JIM WATSON/AFP/Getty Images)

As Niantic spun out of Google (and as it was finishing Pokémon GO) in October of 2015, it dropped from about 80 employees down to about 40. They’d raised money, but it was only enough to keep them going for about two years.

They needed to get Pokémon GO out the door long before then, to prove to everyone involved that the concept worked and give themselves time to course correct if not. A summer launch was ideal, when the weather was best and their biggest potential audiences (North America and Japan) would have more free time to play.

Getting it done by Summer of 2016 meant shelving some things for later — it was an MVP of sorts. They opted to hold off on implementing pillars of the Pokémon series like trading and battling, which would end up taking around two years to finally make it into the game.

“There was a lot more we wanted to do with it. We felt like it wasn’t ready yet… but we sort of had to ship.” Says Bo Boghasian, a Senior Software Engineer at Niantic “It’s just where the company was. Obviously you know what became of it. We were all just like… is this real? It was like a Truman Show moment. I thought everyone who was playing our game was acting.”

The absence of these features hardly went unnoticed, but it didn’t do much to stymie the ridiculous hype surrounding the game’s launch. And when trading and battling eventually shipped, the news served as little hype aftershocks; for many players who’d gotten bored and moved on, these launches were a big enough reason to give the game another look.

Still, in hindsight, the team says it would have been nice to have the next steps a bit more locked in before going live. Especially with regards to things that would’ve kept players happy while Niantic was busy fixing bugs and getting servers stable.

“We were always on the backfoot. We were always reactive with that launch.” says Niantic’s Archit Bhargava. “We were just playing catch up.”

“If there’s one thing we really want to check boxes on with Harry Potter, it’s that we want to come in armed with ideas and tactics that we can take advantage of at launch,” he continues. “To give an example: people all over the world, with the launch of Pokémon GO, were creating these mini-meetups. There was this San Francisco Pub Crawl with 7000 people … We had these organic things emerge, and we were never in a place to help with that, assist with that, and really work with the community.”

“How do we ensure that we can truly work with the community in a positive way?” he adds, “If there’s an organic meetup happening, how do we work with them, and help connect them with other people who might be playing?”

Scaling is hard, even when you’ve done it before

About 5.000 people showed up at a Pokémon Go meeting near Cloud Gate in Chicago. (Photo: Lucia Maffei/TechCrunch)

“Don’t underestimate the power of the viral uptake of your game. That’s the biggest one. That’s the big lesson learned from [GO].” says Niantic CTO Phil Keslin. “Nobody — nobody, within the company, or outside the company — expected what happened with that title.”

The team that built Pokémon GO wasn’t new to product launches. The earliest members came from all over Google, and helped launch massive online products like Google Maps and Google Earth.

And yet…

Pokémon GO’s servers were spotty for weeks after launch. For many newcomers, the game would just sit at its loading screen and spin, or throw up an error announcing that it had “failed to get game data from the server.”

“Who could’ve predicted we would have a global, worldwide phenomenon of that scale?” says Edward Wu, VP of Platform development at Niantic. “We did our homework. We looked at what our launch size could be. I looked at previous mobile game launches of top-ranking IP, and looked at their growth curve over time, and multiplied that by five to provision our resources.”

Server traffic at Pokémon GO’s launch was 50x the company’s “worst case” projections. Way, way too many people were trying to get in, and the servers just weren’t scaling the way they expected. They’d planned to roll the game out country-by-country — but each time they brought a new country online, the servers crashed again. They ultimately called in the Google Cloud team to help them get things stable.

Most games won’t see the viral uptake that GO saw at launch, of course. As we learned in Part II, there were a ton of factors that swirled together to make that phenomenon pan out — the Pokémon IP, the nostalgic/generation-bridging timing of it being the 20th anniversary of Pokémon’s debut, the novelty of all of it, and plenty of other things we’ll probably never really realize. Hell, the game’s downtime probably played some part in the demand; there’s hype to be had in “so many people are trying to play that no one can play!”

But even for a team with heaps of collective experience, scaling issues can come smashing down on the party. It’s a handy reminder: even if you’re pretty confident things will scale fine, it’s a good idea to have graceful failure modes and, ideally, ways to communicate directly with players through the app even when the main gameplay server is down.

As for how the company expects the servers to fair if Harry Potter’s launch proves to be as big as Pokémon GO’s:

“There are two ways here we’re much more ready,” says Edward. “One is that we know, very much, the scale of this. It’s an order of like… large fractions of the planet playing. Two, there are things on the platform technology side that you just won’t run into until you hit scale [like Niantic did with GO]”

“Everyone who launches a large scale service runs into these problems as they scale up.” he says. “The only difference was for us, we were on the back of a rocket ship and we had to do it as it was in flight.”

As your userbase grows, so do your responsibilities

John Hanke speaking at Comic-Con 2016. Photo by Gage Skidmore

Even in these relatively early days of AR, augmenting reality inherently means mixing virtual worlds with the real one. Doing that presents new problems and questions that few people had even considered a decade ago.

What if someone endangers themselves or others in the real world while playing your game — by say, playing while driving a car? You can hope that most people wouldn’t… but when you’re multiplying things out to a playerbase of hundreds of millions, “most people” still leaves plenty of people making awful decisions. Shortly after launching GO, Niantic added speed caps that aim to keep users from playing if the game detects they’re moving too quickly; Pokémon stop spawning, and Pokéstops no longer give items. They added messages reminding players to “be alert” while playing, and to not trespass on private property. Every time the game opens, there’s some reminder to make good decisions.

And what about the day-to-day decisions the company itself makes? If they place some digital goodie in the virtual world that leads people to the corresponding spot in the physical world… what if the person who owns that real-world spot wants nothing to do with it? Who owns the virtual world?

Most people would probably say whoever owns the physical space should command what happens in the virtual equivalent, as the latter has much grander impacts on the former. Within weeks of GO’s launch, Niantic had a page setup for property owners to submit requests for the removal of Pokéstops and Gyms in a location.

But a page like that can only do as much as the team monitoring it, and they couldn’t keep up. Property owners sued Niantic, arguing that requests weren’t honored quickly enough; in February of 2019, Niantic settled by promising to resolve all complaints within 15 days and set up a blacklist that prevents those in-game spots from springing back up within 40 meters of the property.

“Making sure that we have all the operations tools and support surrounding our games, so that, when people write in, or property owners write in and say, ‘Hey, we love your game, but we need to move this in this direction a bit’ or to make sure that the data being presented is the right set of data being presented… making sure that we’re completely and utterly prepared for that I think is a key lesson,” says Edward Wu.

“I will say that I feel extremely fortunate working with incredibly experienced hands at this with John [Hanke], and Phil [Keslin], and our VP of operations Lenette [Posada Howard], who have deep experience on how geodata interacts with the real world” he adds, “and how we have to make sure we listen to all of our constituents, not just our players. We were fairly prepared for that the first time around, but just knowing the scale at which it happens is important.”

It’s only going to get more complex, particularly as Niantic dives deeper into things like the ‘AR Cloud’ — which, as we described in Part III, is essentially a 3D map of the environments in which people are playing. Players would help to build this map — or “point cloud”, as it’s sometimes called — by submitting photos of an area which are then stitched together and analyzed for their 3D geometry.

This point cloud would help to give our devices a high resolution, three dimensional understanding of the space around them; not just the buildings we can model from satellite data, but the park benches, the trees, the statues, and the mailboxes around them. This 3D map would give your device a much more accurate understanding of precisely where it is in the world, and what’s around it. It could also double as a virtual “layer” where digital items and beings can exist persistently, always there but invisible without some sort of AR viewer (be it a phone or a pair of AR glasses.)

Lots of companies (Apple, Google, Snapchat, etc) are poking around this broader concept of 3D mapping the world one point at a time, but there are still lots of questions to be answered. What can be mapped? What shouldn’t be? Is it fine for a company to build a 3D map of the outside of a house, but weird to map the inside? Is the front yard okay, but not the backyard? Where’s the as-of-yet undetermined line where people start to get weirded out? How does this vary region by region? No one really has any idea.

Niantic seems to be approaching this area with care, and perhaps a degree of caution. As of April 2019, the AR Cloud isn’t actually a part of their titles yet. But when it does roll out, John Hanke has said that it’ll start in parks and plazas — in other words, the public places where no one would really contest a big company building a 3D map. It looks like Niantic is trying to figure out where the line is here before it’s crossed.

Visual designs can have growing pains too

Design is hard, and not always for obvious reasons. Making something look good is one big step, but looking good doesn’t mean it’s getting the right point across.

It turns out that when you’re trying to get players to move around the real world, as Niantic is with its games, less is more. Extra visuals can be detrimental. A bit of tall grass or a big swaying tree might look pretty on the in-game map… but if there’s no corresponding grass or tree in real life, players might lose that sense of how the game connects to the world. How do you turn right at a tree that doesn’t exist?

Dennis Hwang, Niantic’s head of visual design, refers to it as a sort of “cognitive dissonance”.

“Our app is almost like a map application, more than a game application in a lot of ways, because you’re having to help the player navigate the real world,” he says. “There were a lot of interesting insights and lessons we learned on aiding navigation, or going against it. If you do it the wrong way, it creates this sense of cognitive dissonance; If you put a tree where this is no tree, or if you put up a big structure like a lamp post and there really isn’t one in the real world… Those are kind of real unique challenges to our type of game experience, and they just get in the way of the player experience.”

Even beyond the map, when you’ve got tens of millions of people poking around your product, it’s easy for seemingly inconsequential decisions to unintentionally lead some users down the wrong rabbit hole.

I mention something I remember from the early days of Pokémon GO to Dennis, when players were still figuring out exactly how the game worked. Some players noticed that if you held your thumb on certain in-game menus, they’d light up in different colors. Was this some sort code input method, they wondered? The key to unlocking some Pokémon? People tried pushing the buttons in all sorts of different orders, but it didn’t seem to lead anywhere.

“It’s amazing that they try to analyze every little thing like that, even bugs.” says Dennis. “That’s the sense of responsibility I feel now to every design decision; I try to make it as clear as possible, as enjoyable as possible, as simple and accessible as possible, so we don’t lose sight of that wide demographic enjoying the game”

Social features can be useful for more than just growth

A group of Pokemon Go users playing Pokemon gathered outside the State Library of Victoria Melbourne, Australia. (Photo by Asanka Brendon Ratnayake/Anadolu Agency/Getty Images)

Pokémon GO is a rather social game. Many players tend to roam around together and catch Pokémon as they chit-chat, and catching the biggest/baddest Pokémon in the game can require groups of up to 20 people to show up and work together in “raids”.

But Pokémon GO really didn’t have any social features baked in at launch. You couldn’t “friend” another player, for example; you could walk around and play with them as often as you liked, but there was no in-game benefit versus just playing with any rando.

Two years after launch, they added a friend system. It rewards you for interacting with other players on a daily basis; by sending them postcard-like gifts from PokéStops you’ve visited or by going on big group raids together, you level up your friendship. Amongst other things, higher friendship levels means your Pokémon are stronger when battling alongside each other, and you got more chances to catch the post-raid Pokémon. It’s proven to be a hit.

“When we launched this friend list and gifting feature last year, we never thought it’d be that successful,” says Kei Kawai, Director of Product at Niantic “But we had hundreds of millions of friend connections, and you know, billions of gifts exchanges in the first few months.”

The friend system gives players one more reason to open the game each day, which is obviously a good thing for Niantic. But the company has found ways to repurpose it for things beyond growing daily actives; the social features have spiderwebbed out through Pokémon GO, allowing Niantic to build things that might’ve otherwise broken the game.

Take trading, for example. Trading had the potential to take the fun out of the game; if you could join and immediately go on eBay and find some cheater who’d warp to your location and give you the rarest Pokémon for 20 bucks, the game’s focus on going outside and collecting stuff starts to fall apart.

Instead, trading relies on friendships built up over time. If you’re not friends, you can’t trade. If you’ve just become friends, both players will need to spend lots and lots of in-game points (many days worth of playing) to trade anything rare. Only after about 90 days of interacting with someone does it become reasonable to make big trades. For people who play together often, trades become dirt cheap — but for anyone trying to cheat the system, it’s probably not worth it.

Says CTO Phil Keslin on using techniques like this to minimize cheating:

“The standard approach is to use some mechanism to detect it and shut it down. Our approach tends to be more holistic. You’ll need the mechanisms to detect and stop it — but if you create economic disincentives for spoofing, they can be just as powerful. If you don’t create an incentive for people to actually go off and do these things, then they won’t do it.”

Get users rolling as fast as possible

If you take away the draw of the franchise, Pokémon GO still has one huge advantage over Ingress: it’s way, way easier to start playing.

As I wrote in Part II:

“Whereas Ingress might challenge a new player to walk a few blocks to find their first objective, a player’s first Pokémon would basically spawn at their feet.”

One of the first challenges with designing Ingress was getting players to understand that to move in-game, they needed to move in the real world. Unless you happened to live right on top of an in-game point of interest, you can’t really do much in Ingress without walking around. But if a player has to walk three blocks just to know what your game is about, they may very well just bounce before the game even starts.

Pokémon GO tackles this same problem, but it brings your first objective to you. Open the game, get your account/character set up, then bam: the three starter Pokémon show up right in front of you. Want more Pokémon? Now you need to get up and walk.

“The onboarding experience for GO is something that is pretty good. It’s really good relative to Ingress,” says John Hanke. “The ability to start playing the game immediately upon downloading it, to not be stumped by the fact that it is a real-world game. I think that’s been one of the big impediments to the adoption of Ingress: you start the game, and you can’t do anything from where you’re sitting. You have to wait until later. […] There’s a huge difference in terms of adoption of the game, and it’s a pretty simple concept.”

Communication keeps users happy

The Pokemon “Pikachu” is seen at the amusement park in Tokyo, July 13, 2016. (Photo by Hitoshi Yamada/NurPhoto via Getty Images)

With Ingress, Niantic had been pretty good about maintaining communication with its players. Early player feedback sessions over beers in Rome played a role in inspiring the massive player real-world gatherings Niantic throws today.

But right after the launch of Pokémon GO, communication took a bit of a dive.

When the servers were down and no one could log in, an update went out with patch notes that outlined little more than “minor text fixes”. Game-changing features would ship out of nowhere, with minimal clarification as to what was happening. When one player wrote in to let customer service know they never received their $10 in-app purchase, the response was nothing but the letter “r”. It became a meme.

The lack of communication wasn’t deliberate. Post-spinout and post-PoGo launch, they just couldn’t keep up.

“We were often accused of not being transparent in the early days, and not communicating clearly,” says Archit Bhargava. “We were trying our best, but this was just new. It was new territory. Now that we have multiple years of experience with that, I think we are in a better place to talk about things. Not just the ‘what’ of what to expect, but here’s a little bit of the ‘how’ and ‘why’. Here’s why we decided to do things this way. Or, if things aren’t working a certain way, here’s what’s truly going on and what we want to improve.”

As they staffed up, it became clear how crucial communication was. The more they communicated, and the more transparent they were, the happier players seemed to be.

“Even though a lot of our fans may not agree on how a feature is designed, they appreciate that we took the time out to explain it to them,” says CMO Mike Quigley.

“They’re not always going to love what we build, or what we do,” he adds “but at least they know what our rationale or thinking was.”

The positive effects of being more transparent make sense. Players want to understand why things are changing, especially if its a change they disagree with. Explain it, and there’s something to point at and cite. Leave it a mystery, and they’ll argue it amongst themselves. Internet arguments rarely make anyone happy.

Nowadays, changes to Pokémon GO tend to come with deep explanations. When they have to make Pokémon stronger or weaker for the sake of balance, they explain why and when it’ll happen. Patch notes break down changes point by point — sometimes even before those things are ready to roll out. When they ship a big new feature, the dev team behind that specific feature explains the thinking. They’ve got people answering questions on the various GO subreddits, and they give popular Pokémon GO YouTubers a heads up before big things happen. Communication is impossible to get perfect, but they’ve taken some pretty huge steps since launch. And, at least anecdotally, players do seem happier.

Niantic EC-1 Table of Contents

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product launch strategy

- Part 3: Brand building and expansion

- Part 4: Growth strategy

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.