What is Niantic? If they recognize the name, most people would rightly tell you it’s a company that makes mobile games, like Pokémon GO, or Ingress, or Harry Potter: Wizards Unite.

But no one at Niantic really seems to box it up as a mobile gaming company. Making these games is a big part of what the company does, yes, but the games are part of a bigger picture: they are a springboard, a place to figure out the constraints of what they can do with augmented reality today, and to figure out how to build the tech that moves it forward. Niantic wants to wrap their learnings back into a platform upon which others can build their own AR products, be it games or something else. And they want to be ready for whatever comes after smartphones.

Niantic is a bet on augmented reality becoming more and more a part of our lives; when that happens, they want to be the company that powers it.

This is Part 3 of our EC-1 series on Niantic, looking at its past, present, and potential future. You can find Part 1 here and Part 2 here. The reading time for this article is 24 minutes (6,050 words)

The platform play

After the absurd launch of Pokémon GO, everyone wanted a piece of the AR pie. Niantic got more pitches than they could take on, I’m told, as rights holders big and small reached out to see if the company might build something with their IP or franchise.

But Niantic couldn’t build it all. From art, to audio, to even just thinking up new gameplay mechanics, each game or project they took on would require a mountain of resources. What if they focused on letting these other companies build these sorts of things themselves?

That’s the idea behind Niantic’s Real World Platform. This platform is a key part of Niantic’s game plan moving forward, with the company having as many people working on the platform as it has on its marquee money maker, Pokémon GO.

There are tons of pieces that go into making things like GO or Ingress, and Niantic has spent the better part of the last decade figuring out how to make them all fit together. They’ve built the core engine that powers the games and, after a bumpy start with Pokémon GO’s launch, figured out how to scale it to hundreds of millions of users around the world. They’ve put considerable work into figuring out how to detect cheaters and spoofers and give them the boot. They’ve built a social layer, with systems like friendships and trade. They’ve already amassed that real-world location data that proved so challenging back when it was building Field Trip, with all of those real-world points of interest that now serve as portals and Pokéstops.

Niantic could help other companies with real-world events, too. That might seem funny after the mess that was the first Pokémon GO Fest (as detailed in Part II). But Niantic turned around, went back to the same city the next year, and pulled it off. That experience — that battle-testing — is valuable. Meanwhile, the company has pulled off countless huge Ingress events, and a number of Pokémon GO side events called “Safari Zones.” CTO Phil Keslin confirmed to me that event management is planned as part of the platform offering.

As Niantic builds new tech — like, say, more advanced AR or faster ways to sync AR experiences between devices — it’ll all get rolled into the platform. With each problem they solve, the platform offering would grow.

But first they need to prove that there’s a platform to stand on.

Harry Potter: Wizards Unite

Niantic’s platform, as it exists today, is the result of years of building their own games. It’s the collection of tools they’ve built and rebuilt along the way, and that already powers Ingress Prime and Pokémon GO. But to prove itself as a platform company, Niantic needs to show that they can do it again. That they can take these engines, these tools, and, working with another team, use them for something new.

If they’re going to work with more third parties in the future… what will those teams need? What works? What doesn’t? What needs more documentation? Can they launch another title without the server meltdowns of the early days of GO?

Enter Harry Potter: Wizards Unite.

Shortly after Pokémon GO launched, it seemed like somehow, some way, people already seemed to know what Niantic’s next project would be: a Harry Potter game. People were referring to it as “Harry Potter GO” oh so matter of factly. It’s like they were trying to will it into existence.

Of course, every fan base thought their franchise should be next. But the Harry Potter rumor just seemed to linger. It would pop up, get debunked, only to pop up again and again.

No one involved in the project wants to say when development officially started, but Niantic CEO John Hanke says there was at least one early email thread with Warner Brothers about the possibility of a Harry Potter AR game even before Pokémon GO launched.

But as we learned in Part II, Niantic at that time was tiny. As the team spun its way out of Google in 2015, it dropped from roughly 80 employees to fewer than 40. They needed to finish Pokémon GO, get it shipped, get it stable, all while keeping its first title, Ingress, moving along. They couldn’t put effort into any other games yet.

It wasn’t until November of 2017, or 16 months after the launch of Pokémon GO, that Harry Potter: Wizards Unite would be officially announced — and even then, it was mostly just to say “Yeah, we’re working on this.” It was another 16 months until they actually told anyone anything about it.

Harry Potter: Wizards Unite is a collaborative effort between Niantic and Warner Bros. Games SF. It’ll be released under WB’s Portkey label, which the company founded in 2017 as an umbrella for games that exist outside of the book/movie canon. Extended universe sort of stuff.

There’s a ton of overlap when it comes to which of the two companies is building what aspect of the game, but from what I’m told it sounds like Niantic is mostly focusing on the stuff behind the curtain — everything on the platform side, like the map engine, the networking, and the AR tech — while WB Games’ main focus is the stuff you’ll see in game, like the story, the content, and the art and animation.

The actual launch date for Wizards Unite is still up in the air, with the teams involved only officially promising that it’ll arrive “later this year.”

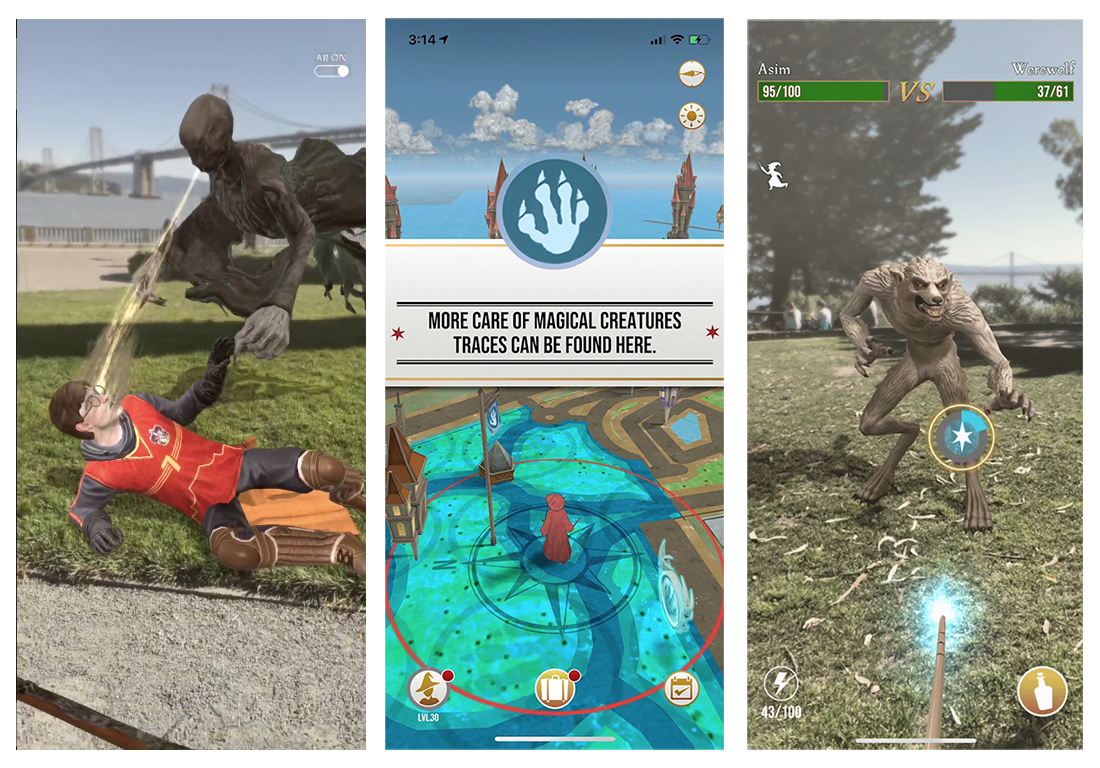

I played a pre-release build of the game at WB Games’ offices in San Francisco in late March. It was unfinished and undeniably a work-in-progress, but the core of the game was there.

I’m not going to go super deep on the game’s mechanics; TechCrunch’s Devin Coldewey also went hands-on with the title and did an excellent job of wrapping everything up he saw. The game is a bit more polished now, but if you’ve already been paying close attention to Wizards Unite news as it trickles out, know that the fundamentals I saw remain the same. Alas, I wasn’t allowed to take any screenshots; imagery here is provided to the press by WB Games.

But what’d I think?

The game is good. The visuals are on point, the bits of voice acting I heard were outstanding, and there’s an absolute trove of lore and references for Harry Potter fans to dig through.

Will it see the same ridiculous levels of sidewalk-dominating popularity that Pokémon GO saw in 2016? That’s tougher — impossible, really — to say. Countless factors went into that game’s viral success, many of them only clear in hindsight.

But Niantic has a lot of things priming it for a big launch here. It’s got the Ingress and Pokémon GO playerbases, much of which will check a new Niantic game out of curiosity alone. It’s got the hype of inevitable “the Pokémon GO-style Harry Potter game is here!” headlines.

And, of course, it’s pretty much guaranteed to be a hit among Potter fans. They were asking for Harry Potter GO, and that’s what they’re getting. And then some.

Instead of playing as Pokémon trainers, players here are wizards; instead of throwing Pokéballs, you’re casting spells; instead of catching Pokémon, you’re collecting a record of wizard-y things that have suddenly and mysteriously started appearing in all sorts of places they shouldn’t.

And of course, there’s the map. Like everything of Niantic’s to date, Wizards Unite primarily takes place on a map. To move your player in-game, you move around the real world to interact with in-game locations tied to Niantic’s massive database of landmarks and points of interest. Whereas GO uses these points as “Pokéstops” and “Gyms”, Wizards Unite has “Inns”/”Greenhouses”, where you’ll get items, and “Fortresses”, where up to 5 players band together to take down sets of enemies like werewolves and pixies.

There are clearly lots of parallels — that’s kind of the point with the platform approach, after all. But Niantic and WB Games have put enough new flavor on things to make it feel like something unique. They’re able to take what they already know works and build upon it, while adding new elements that seem to fit when viewing the concept through the lens of a different franchise. In the case of Wizards Unite, that means a heavier emphasis on plot and player progression.

Pokémon GO doesn’t have much of a plot. It’s never really needed one. If you know Pokémon, you know the gist: go outside, catch Pokémon, maybe battle them at some point. You want a plot? Here are a bunch of new Pokémon, now go catch them too.

Wizards Unite comes at it from the opposite direction. The idea of catching or collecting things isn’t as inherent to the Potter franchise; meanwhile, the series’ fans are used to keeping track of a thousand characters, myriad spin-offs, and winding storylines. WB Games seems to know that, and it’s building the game with that in mind. You want plot? Good! Players will piece together the story through fragments discovered in-game, and it’s already roadmapped out for years.

They’re still keeping the story mostly under wraps, but it has something to do with a group called the “London Five” that has gone missing. A big bad event called “the calamity” is causing stuff from the wizarding world to appear all over the planet, and you need to help gather it back up. Who are the London Five, and where did they go? Who or what caused the calamity, and why?

Meanwhile, each player can pick one of three professions: auror, magizoologist, or professor. As you progress, you’ll be picking and choosing your way through your profession’s skill tree, determining the strengths you bring to those aforementioned multiplayer fortress battles. In GO, your contributions to group efforts are the Pokémon you’ve collected and powered up; in Wizards Unite, it’s the skills you’ve chosen to unlock and bring with you into battle. Tired of your profession, or your group’s go-to auror is out sick? You can switch without losing progress.

Niantic and WB Games probably could’ve just done a cash grab graphics swap here (literally just taking Pokémon GO and popping in assorted Fantastic Beasts) and made a small mountain of money in 1/10th of the time. Instead, they built on top of the concepts that clearly work — and the platform that Niantic has already built — while building a game that’s meant for Potter fans to lose themselves in.

So when will it launch? In an interview with the Los Angeles Times, Kevin Tsujihara (then the CEO of Warner Brothers) referred to it as “coming out this summer”, but it’s unclear how official that is.

If the goal is to maximize the number of people who can play at launch, waiting to launch until it’s summer in the northern hemisphere would be a smart move. Summer means school break, and good weather. Japan and the US are Niantic’s top two audiences by player base and revenue, and both are in the northern hemisphere — as is the UK, where everything Harry Potter started. Pokemon GO launched in the middle of July, and that timing almost certainly played no small part in its outrageous popularity.

Future Tech

Wizards Unite builds on Niantic’s platform as it exists today — but as the company grows, as it tackles new problems in augmented reality, and as new devices and technologies become available, the platform is meant to grow with it. What about six months, or a year, or 10 years down the road? What does the platform look like then?

One of Niantic’s focuses, moving forward, is figuring out how to make augmented reality more real.

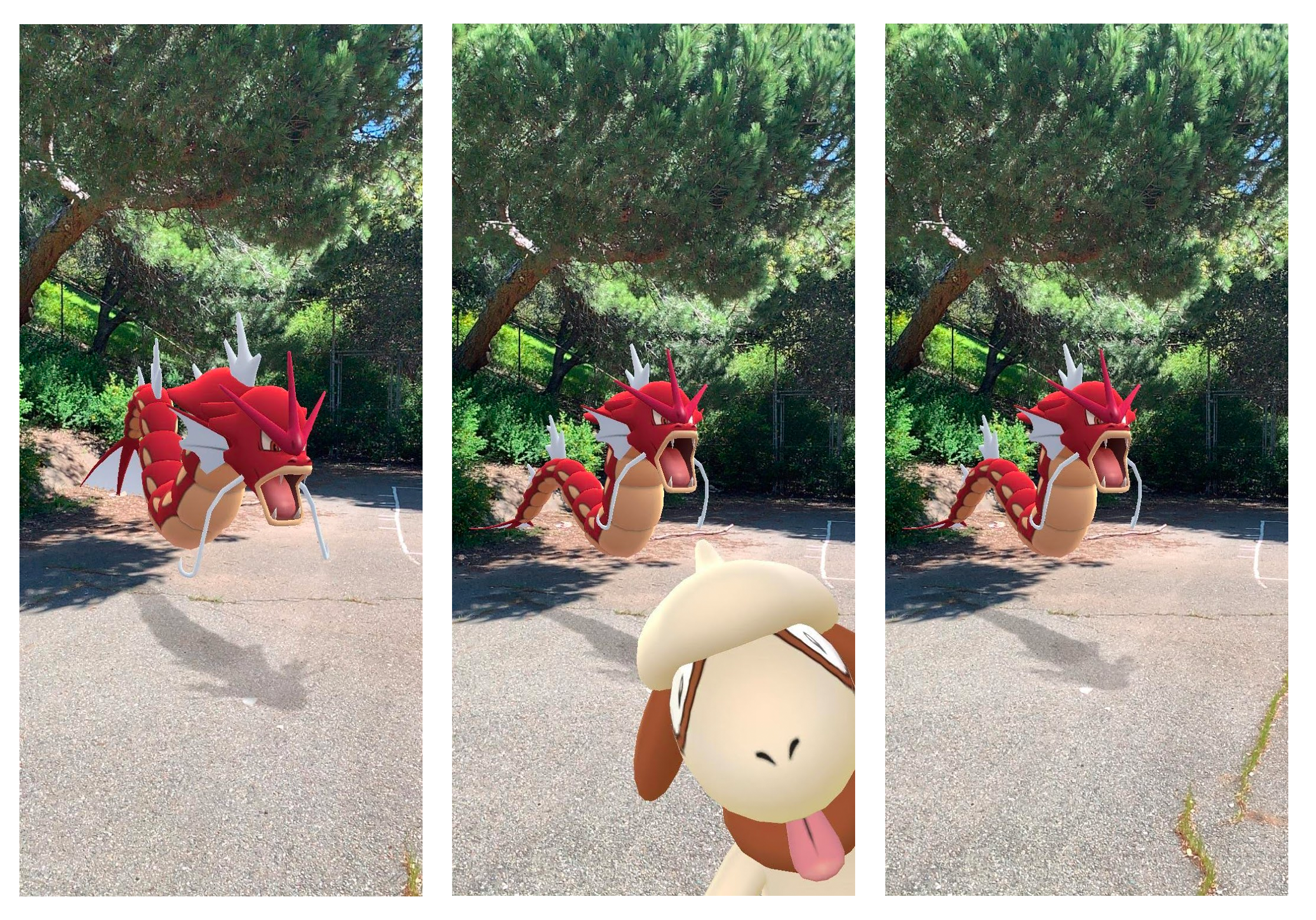

Even nearly three years after Pokémon GO’s launch, Niantic isn’t able to do everything it wants to do with the game. Unlike the very first trailers the company released, we’re not all looking up to the sky to see Mewtwo swooping through skyscrapers. Charizards aren’t hiding behind boulders, and Gyarados aren’t appearing to leap out of the ocean in front of us. The tech just isn’t there yet, and there are a bunch of puzzle pieces that need to be put in place before it gets there.

One part of this puzzle is the current limitations of how our devices understand the world in front of them. Take, as an example, occlusion. In the context of augmented reality, occlusion means blocking parts of a virtual object or character to make it appear as if it’s behind something in the real world. If you want Charizard to hide behind that boulder, your device has to be able to detect the boulder and its shape to know which parts of Charizard shouldn’t be showing. Want Pikachu to run under a desk rather than just sort of float on top of it? Your phone needs to know which parts of the world are desk.

This may seem simple, but occlusion is a super, super tough problem. It’d probably be easier if most of our phones had lasers to help with depth sensing and mapping environments. They don’t. Most phones just have a basic RGB camera or two on the back. It’s a problem that a number of companies are trying to crack, including Google, 6D.ai, and, of course, Niantic.

In June of 2018, Niantic acquired Matrix Mill, a team of six that had spun out of a lab at University College London to work on these challenges. They’re going after the problem with computer vision and machine learning, detecting objects in the environment and making increasingly educated guesses about what they are, and their geometry. Here’s a proof-of-concept video Niantic released at the time showing a few familiar faces running around, hiding behind planters, people, and benches.

As of April 2019, this tech still hasn’t been integrated into the actual release of Pokémon GO. Pikachu and co. still sort of just hover on top of any objects they might otherwise pass behind.

Another part of the puzzle, according to a keynote by John Hanke at Mobile World Congress earlier this year, are the limits of existing cellular technology. The latency is too high, and — as the company learned when networks tanked at GO Fest — capacity is too low. With the looming rollout of 5G networks, both latency and capacity are expected to improve considerably. John says during his presentation that “to do good AR,” they need latency close to 10 milliseconds versus the 100 milliseconds they’re seeing today.

In its most recent round of funding last year, Niantic brought on Samsung as an investor. And that’s for good reason: Samsung is set to be a massive player in the rollout of 5G on both the consumer and network sides of the equation. Niantic wants to be in on that conversation early.

As an example of what it could do with lower latencies, Niantic released a video of a proof-of-concept it calls “Codename: Neon.” Players are able to run around each other, firing orbs of light at each other in real-time through the view of their phones:

It’ll be years before all of these problems are fully cracked. Take the latency and bandwidth advantages of 5G, for example; even with 5G kinda-sorta starting to poke its head up now and with multiple manufacturers releasing early 5G phones, we’re still a good while out from it being widespread enough to truly matter.

And then what? Years from now, are smartphones even still our primary devices? Or have we moved on to something else?

A sci-fi style “mixed reality headset” prop on display in the Niantic lobby. The lobby also has a cabinet full of potion bottles and a steampunk Pokéball.

John Hanke thinks the next phase is glasses. Not “glasses” as in Google Glass; clearly that didn’t work — they messed with the user’s appearance too much, with the term “glasshole” appearing out of thin air almost immediately after their debut. But glasses that have integrated displays while looking more like what many of us wear today? That could be a different story.

He tells me:

The way people interact with AR, or rather don’t interact with AR, is something that we’re still learning a ton about from GO. Even with ARKit and ARCore, it’s… like, what’s AR good for on a handset? Where does it really add fun on a phone?

AR on glasses is a different matter. That’s how you will live, in glasses. On a phone, it’s a mode that you use, and it has drawbacks. It takes effort to hold your phone up. You may feel uncomfortable how you look in public, holding your phone up and waving it around. Maybe people think you’re taking a picture of them. It uses a little bit more battery. There’s a lot of friction around using AR, so it really has to deliver something thats uniquely fun to make it worth doing.

But will people actually want to wear smart glasses? Says John:

I think that we won’t need to convince people to wear them, because this [he holds up his phone and stares at it, as if using it] is actually a huge tax on us. We don’t appreciate it because there’s no alternative.

But when you have something that allows you to get your notifications, to have the communications that you want, to access that information, that doesn’t require you to tie up one of your hands and hold this thing in front of your face and not be able to see or hear things around you, I think it’ll sell itself.

This is going to be less friction, to get the stuff that you want. By less friction, I mean it’s just there. You can continue to talk, to shop, to walk. You can get on the subway, or the bus. But you have that and you’re not juggling your phone and your coffee and your bag.

In November of 2018, Niantic announced an investment in DigiLens, a company building AR glasses. It’s the first and only time, to my knowledge, that Niantic invested in another company rather than acquiring it. I’m told that everything Niantic is building with its real-world platform, it builds with devices like smart glasses in mind.

Meanwhile, Niantic is experimenting with glasses-like tech and what its games might look like through that literal lens. In Japan earlier this year, Niantic and The Pokémon Company exhibited a project it called “Pokémon Scope.” It shows what the world of Pokémon GO could look like through Microsoft’s Hololens:

Be sure to wait until the end, when the video pans up to show the Tokyo horizon, with GO gyms dotting the city.

Mapping, but in 3D

There’s one more piece to this grander AR vision, and it’s perhaps the biggest and most challenging one.

Your phone knows your location, but current GPS tech is really only accurate within a few feet. Even when it’s at its most accurate, it doesn’t always stay there for long. Ever use Google Maps in a big city and had your marker hop around all over the map? That’s probably from the signals bouncing off buildings, vehicles, and all of the myriad metal things around you.

That’s good enough for basic augmented reality functionality seen in Pokémon GO today. But Niantic wants to get closer and closer to the vision of GO’s original trailer, where hundreds of people can look up to see the same Zapdos flying overhead, synchronized in time and space across all of their devices. Where you can gather in a park with friends to watch massive Pokémon battles play out in real time, or leave a virtual gift on a bench for a friend to walk up to and discover. For this, Niantic will need something more precise and more consistent. Like pretty much everything with Niantic, it all goes back to maps.

More specifically, they’ll need to build a 3D map of the environments where people are playing. It’s easy enough to get relatively accurate 3D data about huge things like buildings, but what about everything around those buildings? The statues, the planters, the trees, the bus stops. John, and others in the space, refer to this map as the “AR Cloud.”

John Hanke showing a visualization of the AR Map concept at Mobile World Congress 2019. The point cloud shown is based on the inside of SF’s Ferry Building, just outside of Niantic’s front door. (Image Credit: Niantic/Mobile World Congress)

In early 2018, Niantic acquired Escher Reality, a company that was aiming to “supercharge” AR by making it a shared, cross-platform, real-time experience. The company’s co-founders, Diana Hu and Ross Finman, now lead the company’s platform and AR mapping efforts.

Niantic hasn’t gone too deep on the specifics of how this mapping system would actually work in its games — it seems they’re still working that out themselves. But past reports suggest that players would help build the map as part of playing Niantic’s games, submitting pictures that are analyzed for the edges, lines, and shapes that make up our world. All that data would come together to form a massive, evolving 3D map. It’s sort of like the solution Niantic found with user-submitted Points of Interest in Ingress, just cranked to a ridiculously complex level.

The more users that play, the bigger and more detailed the AR map would get. If something that seemed permanent suddenly isn’t (like, say, a statue gets moved to the other side of a park, or a bench disappears), the data from players will come together to correct the map. Cell towers could store the 3D map data relevant to their surrounding area for nearby player’s devices to grab quickly — also a concept reliant on 5G tech.

A key component of what is sometimes referred to as the “mirrorworld“, this map would be like a digital clone of the physical world; a layer upon which the digital and the physical can co-exist and persist through the looking glass of AR. Hold up your device, have it look for known geometry in the rough area where your GPS says you are, and bam — your device knows exactly where it is in the world(s).

Niantic is among a very limited set of companies positioned to build a “map” like this. Few other companies already have millions and millions of users going outside and waving their phones around statues and buildings and parks around the world like Niantic does with its games. But it’s definitely not the only one thinking about these problems. Google is going after the precise positioning problem with its own augmented reality functionality in Google Maps. AR startup 6D.ai began working on the “AR Cloud” concept very early on, calling it part of their “master plan”. Apple is using cars to build a point cloud of city streets to rebuild Maps. Even Snapchat is using AR to get people to take pictures of buildings now.

But Niantic can’t just flip a switch and start mapping every inch of the world in 3D. That’s a tremendous amount of data for any company to be gathering and processing, and there are huge matters of privacy to be worked out. What areas can be mapped; what shouldn’t be? Many people probably don’t want a company having a 3D map of their living room just because someone played a game there. Governments don’t want soldiers mapping bases through some game on their phones. Fortunately, Niantic seems to be approaching it thoughtfully.

These sorts of things aren’t uncharted territory for John Hanke. In his 10 years in charge of Google’s Geo division, teams under his umbrella were some of the first to see the problems that arise when the virtual and real worlds collide — and they had their share of public stumbles along the way. People sued Street View for taking photos on private roads. Governments demanded that sensitive locations like nuclear reactors and bases be blurred in Google Earth. When Street View cars were found to be collecting data transmitted over unencrypted Wi-Fi networks they drove past while snapping pictures of city streets, it lead to investigations and fines around the world.

Nor is it new territory for the Niantic team as a whole. The company settled a lawsuit just two months ago with homeowners who don’t want Pokéstops near their houses, agreeing to resolve any future complaints within 15 days and build a database to keep them from showing up again. Those same homeowners presumably won’t want Niantic having a 3D map of their house, either.

Part of doing this right — and without freaking out half the planet — will be in limiting its breadth right off the bat. Mapping would start in parks and plazas, John Hanke told Reuters last year. Public spaces, where players already gather. The places that have already proven themselves to work well as in-game gyms, and where most people probably wouldn’t mind some company making a 3D map. John has also talked about the AR Cloud powering experiences in bars and coffee shops — so perhaps open it up to businesses that opt-in, down the road. There’s going to be a mountain of wild and entirely new hurdles like this to figure out as augmented reality continues to trickle into our every day lives, and as the overlap between the digital world and the physical world grows. For Niantic to start down this path the right way, it needs to take baby steps.

Beyond games

Building a platform for others to build upon is a key pillar of Niantic’s strategy, but they’re not going to stop building their own consumer products any time soon. I’m told Niantic has multiple other products on the roadmap to build in-house after Harry Potter.

I ask John Hanke about them. As you might imagine, he doesn’t want to get too specific.

“I think building your own stuff on your own platform is incredibly important to sort of set the course for where the experiences are going,” he says. “To show people what’s possible, to get the most that we possibly can out of it, and to show other developers some of the things they might be able to do.”

Niantic continues to play with concepts to figure out how to make AR fun on phones. AR Photo mode lets users take photos of Pokémon they caught; occasionally, other Pokémon will photobomb the picture, triggering an opportunity to catch them.

“I don’t think we’ll ever not be in the business of creating our own first-party flagship content,” he adds.

I ask why he says “content” and not “games.” Niantic has launched products that aren’t games (remember Field Trip?), but only the games have really found an audience. He replies:

Games and other things.

I think the world of shopping, dating, exercise, and games are much more overlapped in reality than we tend to think of them. We tend to think of those things as being very separate, segregated things – but in real life, you do all of them together. You go out on a date and you might pass through a store.. maybe you’re seeing a movie, or sitting down to play a game somewhere. It’s very fluid, you know? You might go for a run together, or go hang out over a meal.

All those things tend to blend together. So I’m really excited to build applications that feel that fluid, that feel like they could be part of that social process. And not just… okay, this one is the game category, this is the exercise, your dating or social stuff is over here, and your shopping is over there. I think it’s cool to think about all these things! Travel, exploration, place discovery…

Place discovery… like Field Trip? Do they return to that concept?

“I don’t think we’ll do anything exactly like what we did before,” John says. “But that space, I would characterize that as place discovery. Field Trip’s job was to tell you about things around you, and that’s definitely part of the landscape that we occupy, for sure. So we may come back to that.”

Getting to China

China is the biggest market for video games in the world, with players in the country spending a reported $37.9 billion on games in 2018 alone. That’s over 25% more than the next biggest market, the U.S.

And Niantic has never officially shipped a game there.

Releasing a game in China is notoriously challenging, with each game required to get approval from the Chinese government. The impacts can run deep; when the government froze game approvals in 2018, Apple openly said that it put a dent in its financials.

For a U.S.-based company like Niantic, launching a game in China means working with a partner company based in China. When Niantic took an investment from the venture arm of NetEase — the Chinese company that helped bring games like World of Warcraft and Overwatch to the country along with a number of its own titles— people took it to mean a China launch of Pokémon GO was imminent. NetEase was quick to pump the brakes, noting that reports of the game’s impending local launch were just speculation.

But Niantic absolutely wants to release its games in the country.

“One of the company’s [objectives] is to make the world a better place by motivating people to go outside, exercise, be social, and discover new things.” says Masa Kawashima, who leads Niantic’s Asia Pacific operations. “When I think ‘What is the world?’… Is the world only the U.S.? Or Japan? Or Europe? I would say China is a big part of the world! And hopefully there’s a bunch of people waiting for our products. It’s not only about the money; in order to change the world, we can not ignore China.”

“There are a lot of challenges,” Masa says. “But we’ll never give up.”

Where’s the exit?

The early pre-spinout days of Niantic not being able to find investors are long over. The company has raised over $470 million to date, the most recent of which was a $245M Series C in January valuing the company at nearly $4 billion dollars.

The company has been making lots and lots of money since the launch of Pokémon GO — that game brought in over $2 billion in top-line revenue, they’ve disclosed. So why take outside investment?

It’s partly strategic, with the investors being able to bring more to the table than money. There’s the Samsung investment I mentioned earlier, wherein Niantic wants to be as close to the development of 5G as it can, and the NetEase investment which could, perhaps, help the company make its way into China. They brought on Fuji TV as an investor in 2016; two years later, Niantic announced it was working with Fuji TV to create an Ingress anime series. Their Series C included AXiomatic, a company focused on all things eSports — a good fit with Niantic’s live events. A few years down the road, Niantic’s “strategic investors” tend to actually be pretty strategic.

And it’s partly because they can right now. I asked Niantic CTO Phil Keslin why they raised their most recent round. He replies:

It’s a standard rule of startups: when money’s cheap, you should take it. That’s the general rule, right?

The company is in a really good position. You never know what’s going to happen tomorrow. If something happens, god forbid, it’s nice to have a war chest. It enables you to make changes very very rapidly, especially if they’re capital intensive, that you wouldn’t be able to otherwise. And if you’re in dire straits, raising money is very expensive, right? These guys are going to want to take a much bigger part of your company. If the company is in a strong spot, and the money is available, you should take it and prepare for the future.

But when you take on hundreds of millions of dollars, your investors are obviously going to be hoping for a return eventually. So what’s the game plan? Do they have any sort of exit in mind at this point?

Most of the people I ask at Niantic say it’s not really something they talk about. CMO Mike Quigley says the company is “just not wired that way.”

John Hanke goes a bit deeper on the topic, suggesting that while the company keeps its books ready for an IPO if the time comes, it’s not itching to do it:

Our philosophy on that is we owe it to ourselves, and our shareholders, to build the infrastructure of the company so that we could go public at some point in the future if that was the right thing to do. If you want to be a public company you have to do your finances and accounting in a certain way. And we have, you know, two years of audited financials.

You have to do your revenue recognition; on mobile game in-app purchasing, there’s a whole rigorous methodology on how you recognize that revenue. You have to be somewhat sophisticated about making sure you’re in tax compliance in all of your markets. There’s a lot of nuts and bolts stuff that is necessary if you ever want to be a public company, a lot of extra work. And so we’re investing in doing that.

And the other things are just.. there’s no real difference between what we would need to be a public company and what we would need to be just a successful company generally. Having the right kind of infrastructure to hire the best people, having the right kind of HR infrastructure to provide service and benefits to our employees, having a diversified portfolio of products, games, technology. Making the right investment to build that out over the long term. Those are all things that would, you know, serve us well if we were to decide to go public in the future, but they’re also just things that we should do to make sure the company’s strong in the future.

We’re not on a hot path to go public next year, or whatever. A bunch of companies are! But we’re not lined up to do that.

What about being acquired? John continues:

I don’t have a desire to sell the company, because I’ve been through that process of selling a company.

There’s nothing wrong with it, I just don’t have a desire to repeat that. I’ve already worked at Google; I don’t have the desire to go work for another giant company, necessarily.

But it’s bad form, and probably dumb, for a CEO to say ‘Oh I’d never sell the company!’ and then a year later they end up selling the company because someone makes an incredible offer and it obviously makes sense. But that’s not the target; the target is to be independent and figure out how to get liquidity to our employees and our shareholders along the way.

To be continued…

The Niantic lobby.

It started as an “entrepreneurial lab” within Google, at an unclaimed desk in San Francisco. Nowadays it’s around 450 employees spread out across much of the second story of the SF Ferry building, where guests enter the office through the doors of a replica TARDIS.

They’ve launched two games, are about to launch their third, and they’ve got more products in the pipeline. They have their targets locked on becoming a platform upon which others build, and which the company clearly hopes serves as the underlying foundation of all things AR. They’re building products that hit what they see as the limits of today’s mobile technology, building new tech aiming to get past these limits, and are aligning themselves closely with companies that are tackling other parts of the equation. Niantic is a bet on AR, not just AR games.

Throwing back to my question from Part II on how far along Pokémon GO is in its overall life, I ask John how far along he thinks Niantic is in its life today.

He smiles, giving me the same answer: 3%.

Niantic EC-1 Table of Contents

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Product launch strategy

- Part 3: Brand building and expansion

- Part 4: Growth strategy

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.