The FCC voted this morning to nullify 2015’s Open Internet Order and its strong net neutrality rules, substituting a flimsy replacement with a deeply (and deliberately) incorrect technical justification.

The battle is lost. What of the war? Here’s what happens next, and what you can do to help.

First, very little

As rushed as this vote was, it doesn’t make the rest of the government move any faster. Voting to adopt the order doesn’t magically and instantly eliminate net neutrality. First, the new rules have to be entered into the federal register — and that won’t happen for a little while, perhaps a couple of months.

In the meantime, you’re going to get a whole lot of blog posts, opinion pieces in newspapers, speeches, statements, notices of intent and anything else that will keep the topic alive in the public eye.

During this time the FCC will point out that despite having voted in new regulations, the internet has not devolved into a corporate free-for-all. Of course it hasn’t, because the rules haven’t taken effect yet. They will point out that companies could start changing policies or making announcements ahead of that event, but for reasons we’ll go into later, that’s extremely unlikely, even if said companies do have evil intent. At any rate, don’t be fooled.

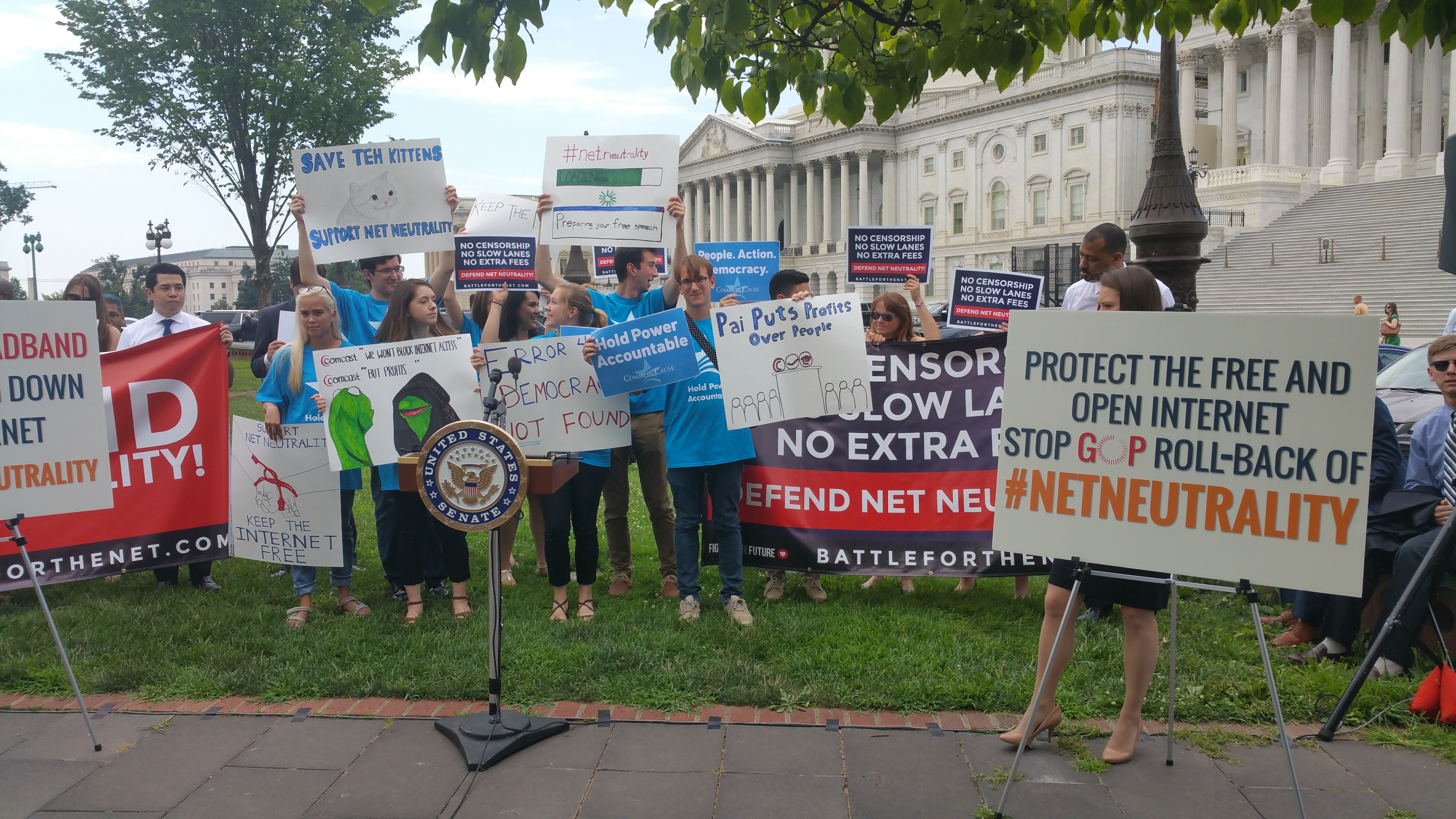

Do, however, continue engaging with your elected officials. They are only engaged in this fight — if they are at all — because their constituents have expressed that it is important to them. If they think they can get away with not paying attention for a few months, or that voters have moved on to another hot-button issue, they’ll gladly spend their time and money pursuing other things. Don’t let that happen. Make sure they are aware (and aware that we’re aware) that this problem isn’t going away.

Early next year: lawsuits aplenty

When the rules get entered in the federal register, the floodgates open. Right off the bat I can think of a number of different lawsuits or challenges that could be filed, though the details are unfortunately beyond my sight.

1. States take issue with preemption. The new order includes considerable provisions preventing states and municipalities from creating rules or regulations that contradict the federal ones. So did the 2015 order, of course — but there’s a big difference. The authority granted to the FCC by Title II made it a force to be reckoned with; it could reach in and quash incompatible state laws or practices. The new rules, however, reduce the FCC’s reach considerably by restoring it to Title I, under which it repeatedly failed to establish or enforce broadband rules. Without Title II, states may ask under what authority do you presume to preempt our laws?

2. Arbitrary and capricious. From its first draft, Restoring Internet Freedom has been predicated on a massive misrepresentation of how the internet works. The details you can find here, but suffice it to say that when the people who actually created the web, internet, encryption, networking layers and all that say you’ve got it wrong, you’ve probably got it wrong.

Now, what you’ll hear about this one is a bit technical: that the Supreme Court in 2005 made a major decision known as “Brand X” establishing the precedent that, in case of ambiguity in the law (like how broadband companies should be defined), the courts would defer to any reasonable interpretation made by an expert agency like the FCC.

In 2005, that was one way; in 2015 they went another way; and in 2017 they’re going back to the first way. But how it’s technically justified in the order now is so demonstrably wrong that it could very well be open to a lawsuit alleging that these rules could very credibly be challenged under the Administrative Procedure Act, which prohibits regulations that are “arbitrary and capricious.”

3. Fraudulent comments and procedural shenanigans. This is a little more hazy, but the cloud hanging over the FCC relating to its handling of the millions of fake comments in its system is a real thing. Congress has repeatedly asked for information on the cybersecurity aspect of this, and New York’s attorney general has gone public with his office’s frustration at being stonewalled by the agency when it comes to identity theft.

Congress could request an independent investigation (and has, actually) and pending the results of that investigation ask that the rule not be enforced. Similarly, the NY AG could sue (in fact he just announced he will) saying the FCC failed to fulfill the requirement of allowing fair and open commentary on its process — even if the FCC is itself not obligated to consult that commentary in its decision.

In some of these lawsuits, the plaintiffs may ask that the new rules be suspended while the court case goes on; this type of “stay” worked with Trump’s travel ban, but it likely won’t work here. That’s because in the latter case, there was evidence of immediate and irreparable harm: people in Iran or Syria might lose their jobs or come to harm because of the rule being challenged. Net neutrality is a serious issue, but the harm it may cause is more subtle. Judges probably won’t be convinced that the new rules need to be stayed for any period of time.

In some of these lawsuits, the plaintiffs may ask that the new rules be suspended while the court case goes on; this type of “stay” worked with Trump’s travel ban, but it likely won’t work here. That’s because in the latter case, there was evidence of immediate and irreparable harm: people in Iran or Syria might lose their jobs or come to harm because of the rule being challenged. Net neutrality is a serious issue, but the harm it may cause is more subtle. Judges probably won’t be convinced that the new rules need to be stayed for any period of time.

These are just basic ideas (I am not a lawyer, thankfully), but they show the variety of ways in which the new rules could be legally challenged. The 2015 order was also subject to lawsuits, but none made a dent; in fact, having the courts repeatedly uphold the order is something that has been key to the arguments of net neutrality proponents.

There’s a risk that the same will happen here, but you can’t win if you don’t play. As for the Supreme Court, the appointment of Gorsuch could be considered a hazard for a progressive verdict, but interestingly it is the famously conservative late Justice Scalia who put forth the most famous argument in favor of classifying broadband as telecommunications. So political alignment may not play as much of a role as some would think in these proceedings.

It will, however, play a major part in others.

Congressional action

Ultimately, as many commentators and the FCC on occasion have pointed out, the question may have to be settled by legislation. Ultimately the FCC derives its authority from laws written by Congress, and if those laws are amended or others appended, it could moot the arguments of the past decade or two.

2018 is, of course, an election year, and a particularly important one for a number of reasons. The majority role in the Senate hangs in the balance, and the House as always is up for grabs, though the Republicans have a more commanding lead there.

Political actions will naturally be divided into two sections: the lead-up to the election and what comes after. I hesitate to speculate on what might happen after the election, as the balance of power may shift considerably.

In the lead-up, however, there will be strong Democratic leadership on the topic of net neutrality, since their constituencies have been particularly vocal about it (and must remain so!).

There are two tacks they might take. First is the possibility of using the Congressional Review Act, which allows Congress to undo recently instituted regulations, to nix the FCC’s plan; Representative Mike Doyle (D-PA) just announced he will do this. This is the most straightforward solution, and one the Republican Congress recently deployed in order to kill several Obama-era regulations, including the Broadband Privacy Rule. That action was particularly unpopular, and Republicans aiming to look progressive may hop on board a Democratic bill. Bipartisan talks will have to take place — this can’t be done without work on both sides of the aisle.

A CRA repeal of Restoring Internet Freedom would be devastating to the FCC’s plans, but likely would leave intact the legislative ambiguities that gave rise to today’s issues.

A true solution would involve amending the 1996 Telecommunications Act. The critical part of all this is the classification of broadband under Title II of the act, and if that could be accomplished by legislation — it would only take a few words — it would put an end to these questions once and for all. However, to amend a major bill is not something a minority party is likely to attempt. And with the threat of a veto hanging over them, it’s very unlikely that this will come to pass until a Democratic president is elected.

Following the vote, I talked with Senator Brian Schatz (D-HI). His advice for the present is simple: “We want every Member of Congress to have to go on the record and say whether or not they agree with what the Commission just did.”

Having everyone take a side makes it a clear issue for debate in the 2018 midterms — and the 2020 Presidential election as well. “We have to take all the outrage and enthusiasm around this issue and turn it into a real electoral force in 2018,” he said, echoing what he told me earlier this year. “2018 has to be the first year of the net neutrality voter.”

Can you find your elected official’s stance on net neutrality? If not, email, call, or tweet at them to ask why not.

ISPs will bide their time

The net neutrality rules may be effectively dead, but there are several reasons why broadband providers won’t make any overt efforts to take advantage of the fact.

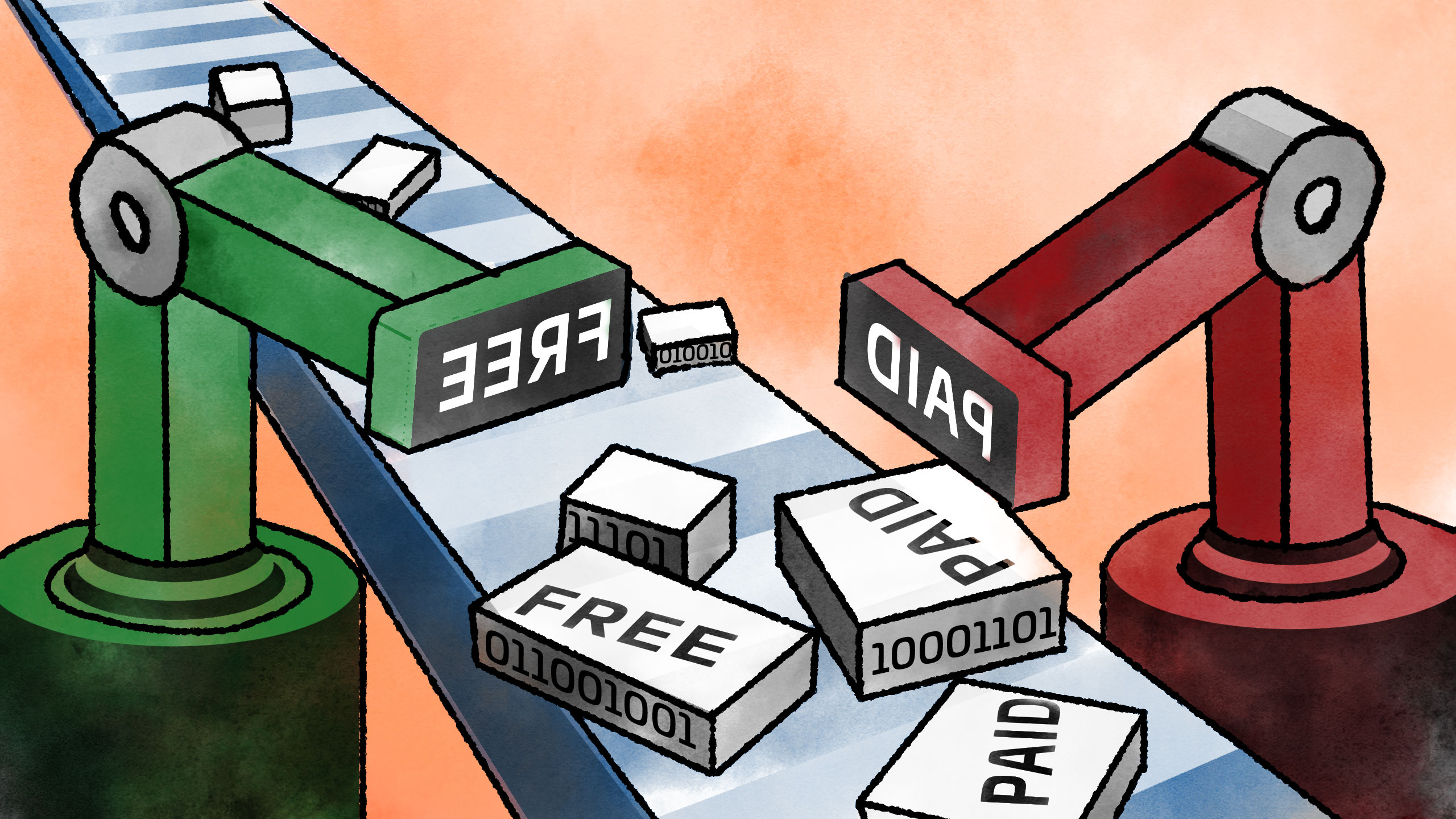

For one thing, everyone is watching them like hawks. ISPs are under extreme scrutiny right now, both from regulators like the FTC (which will be put back in charge of them) to grassroots activists watching for any unseemly network practices. For them to immediately change their practices right after the regulations change would be hypocritical in the context of their repeated arguments that they already respect the no blocking, no throttling, no paid prioritization rules.

Not that major companies generally shy away from a little hypocrisy now and then, but in this case it would be risky; anything they do could and would be used against them in a court of law in one of the cases listed above. Instead, it’s in their interest to appear totally unaffected by all this.

That said, they may try to pull a fast one here and there. You can help here by reporting any changes you do see. TechCrunch will be watching its tip line.

Next, there’s really no guarantee these regulations are here to stay. ISPs have strongly supported Chairman Pai’s plan, but anyone with a brain can see how flimsy the technical justification for re-reclassifying broadband is.

There’s a very real chance that a lawsuit, administrative challenge or bipartisan legislation could reverse these incredibly unpopular new rules. It’s just bad business to use anything so unstable as the foundation for any major practices, and ISPs are plenty aware of that. Imagine the time and money they’d have to invest to institute some fast-lane plan, throttling scheme not considered anti-competitive or what have you — only to have to turn it off a few months later.

No: until the rules are cemented in place or removed, the ISPs will continue just as they have done for the last few years — with a few exceptions.

You can expect them to resume a few programs that have been considered borderline in the past. Zero rating schemes, you can bet, will flourish. And situations where companies are mixing services — Comcast’s Stream TV, for instance, which essentially zero-rated all its own TV traffic — will also get a green light.

You’ll be targeted for these practices, and the details of how they work will be interesting to scrutinize. Ordinary users will be the ones who see these things first in test markets and targeted advertising, so if you see something suspicious, bring it to the attention of your friendly neighborhood tech site.

The ISPs will also make some highly visible investments and expansions in rural areas and chalk them up to the freedom afforded them by the new regulatory scheme. Of course, it will turn out these investments were planned years ahead of time or totally unaffected by Title II. But all the same the companies will act as if a great weight has been lifted from their shoulders.

Basically you can expect broadband providers (including mobile ones) to play it safe while keeping a very close eye on the courts, Congress, and all the rest.

Hang tight

This sucks, to be sure. But the reality is that the effects of net neutrality being nullified won’t be felt for some time, and even then its precarious position means that for the foreseeable future, ISPs won’t go hog-wild.

Your role now is to be the eyes and ears of the attorneys general, members of Congress and advocacy organizations that are fighting on your behalf. The next few months will be spent in preparation, and the months after that in fierce litigation — and if we’re lucky, a few months after that, legislation.

This vote was as good as set in stone a year ago, a foregone conclusion given the fierce partisan divide, but we didn’t stop talking about it or holding companies and officials responsible. Don’t stop now.