Apple is stepping up its artificial intelligence efforts in a bid to keep pace with rivals who have been driving full-throttle down a machine learning-powered AI superhighway, thanks to their liberal attitude to mining user data.

Not so Apple, which pitches itself as the lone defender of user privacy in a sea of data-hungry companies. While other data vampires slurp up location information, keyboard behavior and search queries, Apple has turned up its nose at users’ information. The company consistently rolls out hardware solutions that make it more difficult for Apple (and hackers, governments and identity thieves) to access your data and has traditionally limited data analysis so it all occurs on the device instead of on Apple’s servers.

But there are a few sticking points in iOS where Apple needs to know what its users are doing in order to finesse its features, and that presents a problem for a company that puts privacy first. Enter the concept of differential privacy, which Apple’s senior vice president of software engineering Craig Federighi discussed briefly during yesterday’s keynote at the Worldwide Developers’ Conference.

“Differential privacy is a research topic in the area of statistics and data analytics that uses hashing, sub-sampling and noise injection to enable this kind of crowdsourced learning while keeping the information of each individual user completely private,” Federighi explained.

Differential privacy isn’t an Apple invention; academics have studied the concept for years. But with the rollout of iOS 10, Apple will begin using differential privacy to collect and analyze user data from its keyboard, Spotlight, and Notes.

Differential privacy works by algorithmically scrambling individual user data so that it cannot be traced back to the individual and then analyzing the data in bulk for large-scale trend patterns. The goal is to protect the user’s identity and the specifics of their data while still extracting some general information to propel machine learning.

Crucially, iOS 10 will randomize your data on your device before sending it to Apple en masse, so the data is never transported in an insecure form. Apple also won’t be collecting every word you type or keyword you search — the company says it will limit the amount of data it can take from any one user.

In an unusual move, Apple offered its differential privacy implementation documents to Professor Aaron Roth at the University of Pennsylvania for peer review. Roth is a computer science professor who has quite literally written the book on differential privacy (it’s titled Algorithmic Foundations of Differential Privacy) and Federighi said Roth described Apple’s work on differential privacy as “groundbreaking.”

Apple says it will likely release more details about its differential privacy implementation and data retention policies before the rollout of iOS 10.

So what does this mean for you?

Keyboard

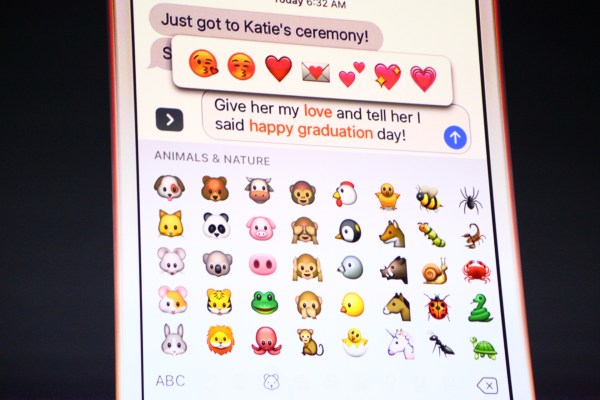

Apple announced significant improvements to iMessage yesterday during the WWDC keynote. Differential privacy is a key component of these improvements, since Apple wants to collect data and use it to improve keyboard suggestions for QuickType and emoji. In iOS 9, QuickType learns phrases and updates the dictionary on your individual device — so if you type “thot” or “on fleek” enough times, autocorrect will eventually stop changing the phrases to “Thor” and “on fleet.”

But in iOS 10, Apple will use differential privacy to identify language trends across its billions of users — so you’ll get the magical experience of your keyboard suggesting new slang before you’ve ever used it.

“Of course one of the important tools in making software more intelligent is to spot patterns in how multiple users are using their devices,” Federighi explained. “For instance you might want to know what new words are trending so you can offer them up more readily in the QuickType keyboard.”

Differential privacy will also resolve the debate over which emojis are most popular once and for all, allowing for your emoji keyboard to be reordered so hearts aren’t inconveniently stashed at the very back near the random zodiac signs and fleur-de-lis.

Spotlight

Differential privacy builds on the introduction of deep linking in iOS 9 to improve Spotlight search. Federighi unveiled deep linking at last year’s WWDC using the example of recipes. He demonstrated that searching for “potatoes” in Spotlight could turn up recipes from within other apps installed on his device rather than merely surfacing web results.

As more and more information becomes siloed in apps, beyond the reach of traditional search engines, deep linking is necessary to make that content searchable. However, questions remained about how iOS 9 would rank deep-linked search results to prevent app developers from flooding Spotlight with irrelevant suggestions.

Apple plans to use differential privacy to address that concern. With obfuscated user data, Apple can identify highly popular deep links and assign them a higher ranking — so when you’re using Spotlight to look for potato recipes, you’ll get suggestions for the most delicious potato preparations apps like Yummly have to offer.

Notes

Notes is the final area where iOS 10 will apply information gleaned through differential privacy to improve features.

Federighi also discussed the upgrades to Notes during yesterday’s keynote. In iOS 10, Notes will become more interactive, underlining bits of information that’s actionable — so if you jot down a friend’s birthday in Notes, it might underline the date and suggest that you create a calendar event to remember it.

In order to make these kinds of smart suggestions, Apple again needs to know what kinds of notes are most popular across a broad swath of its users, which calls for differential privacy.

How it works

So what exactly is differential privacy? It’s not a single technology, says Adam Smith, an associate professor in the Computer Science and Engineering Department at Pennsylvania State University, who has been involved in research in this area for more than a decade, along with Roth.

Rather, it’s an approach to data processing that builds in restrictions to prevent data from being linked to specific individuals. It allows data to be analyzed in aggregate but injects noise into the data being pulled off individual devices, so individual privacy does not suffer as data is processed in bulk.

“Technically it’s a mathematical definition. It just restricts the kinds of ways you can process the data. And it restricts them in such a way that they don’t link too much information about any single interval pick up points in the data set,” says Smith.

He likens differential privacy to being able to pick out an underlying melody behind a layer of static noise on a badly tuned radio. “Once you understand what you’re listening to, it becomes really easy to ignore the static. So there’s something a little like that going on where any one individual — you don’t learn much about any one individual, but in the aggregate you can see patterns that are fairly clear.

“But they’re not as sharp and as accurate as you would get if you were not constraining yourself by adding this noise. And that’s the tradeoff you live with in exchange for providing stronger guarantees on people’s privacy,” Smith tells TechCrunch.

Smith believes Apple is the first major company that’s attempting to utilize differential privacy at scale, although he notes other large commercial entities such as AT&T have previously done research on it (as has, perhaps surprisingly, Google via its Project Rappor). He notes that startups have also been taking an interest.

Despite no other commercial entities having deployed differential privacy at scale, as Apple now intends to, Smith adds that the robustness of the concept is not in doubt, although he notes it does need to be implemented properly.

“As with any technology that’s related to security the devil’s in the detail. And it has to be really well implemented. But there’s no controversy around the soundness of the underlying idea.”

The future of AI?

Apple’s adoption of differential privacy is very exciting for the field, Smith says, suggesting it could lead to a sea change in how machine learning technologies function.

The debate over privacy in Silicon Valley is often viewed through a law enforcement lens that pits user privacy against national security. But for tech companies, the debate is user privacy versus features. Apple’s introduction of differential privacy could radically change that debate.

Google and Facebook, among others, have grappled with the question of how to deliver feature-rich products that are also private. Neither Google’s new messaging app, Allo, nor Facebook’s Messenger offer end-to-end encryption by default because both companies need to vacuum up users’ conversations to improve machine learning and allow chat bots to function. Apple wants to glean insights from user data, too, but it’s not willing to backpedal on iMessage’s end-to-end encryption in order to do so.

Smith says Apple’s choice to implement differential privacy will make companies think differently about the tradeoffs between protecting privacy and improving machine learning. “We don’t need to collect nearly as much as we do,” Smith says. “These types of technologies are a really different way to think about privacy.”

Although iOS 10 will only use differential privacy to improve the keyboard, deep linking, and Notes, Smith points out that Apple may use the strategy in maps, voice recognition, and other features if it proves successful. Apple could also look for correlations between the times of day people use certain applications, Smith suggests.

Apple’s choice not to collect raw user data could encourage more trust from users. Conveniently, it also helps Apple harden itself against government intrusion — a cause that Apple notoriously fought for during its court battle with the FBI.

Since differential privacy has been studied for a decade, it’s a relatively low-risk security strategy for Apple. Smith said Apple’s adoption of the concept hits a “sweet spot” between innovation and user safety.

“Whether or not they’re entirely successful, I think it will change the conversation completely,” Smith says. “I think the way people think about collecting private information will change drastically as a result of this. And that may ultimately be the biggest legacy of this project at Apple, possibly far beyond the financial implications for Apple itself.”