As we saw in parts 1 and 2 of this EC-1, by mid-2013, Nubank CEO David Velez had most of what he needed to get started. He’d brought on two co-founders, assembled ambitious engineering and operations teams, raised $2 million in seed funding from Sequoia and Kaszek, rented a tiny office in São Paulo, and was armed with a mission to deliver the kind of banking services that customers in a market as large and lucrative as Brazil’s should expect.

Despite being named Nubank, however, the startup couldn’t actually be a bank: Brazil’s laws made it illegal at the time for a foreigner-run company to operate a bank. That restriction required the team to develop an inventive product strategy to find a foothold in the market while they waited for a license directly from the country’s president.

Nubank was so adamant about differentiating itself from other banks that it chose Barney purple for its brand color and first credit card.

Nubank therefore pursued a credit card as its first offering, but it had to race against a clock counting quickly down to zero. At the time, Brazil didn’t have ownership restrictions on this product segment like it did with banking, but new rules were coming into force in just a few months in May 2014 that would block a company like Nubank from launching.

The company needed to execute rapidly over the next eight months if it wanted to be grandfathered into the existing regulations. The speed of operations was frantic to say the least, and the company would go on to work even faster, ultimately propelling itself into the stratosphere of fintech startups.

Full faith in credit

It’s easy to assume that the name Nubank refers to “new bank,” but that’s not really what the founders were going for. The word “nu” in Portuguese means “naked,” and Velez and his team wanted the name to reflect their vision: To build a 21st-Century bank without any of the shackles imposed by the traditional banks in Brazil.

The team wanted to offer services to as many people as possible, as there is a huge wealth gap in Brazil, where the minimum wage is around $200 a month.

Launching with just a credit card was both a strategic and practical business decision. Credit cards were widely used in the country, and everyone understood how they worked. Additionally, you could only use credit cards to shop online in Brazil, because debit cards weren’t accepted.

Nubank credit card. Image Credits: Nubank

To attract as wide a user base as possible, the Nubank credit card would offer credit starting at just R$50 per month (about $10 USD), making it accessible for most people in the country. Importantly for Brazil, it came with zero annual fees, and it could be managed fully through a free mobile app.

Nubank was so adamant about differentiating itself from other banks that it chose Barney purple for its brand color and first credit card. “People would say, ‘You can’t have a purple bank! Banks are about being conservative,’” Velez said, referring to the feedback he got before going to market.

That advice wasn’t wrong, but consumers really wanted a completely different experience than they’d had previously with financial institutions — a frame that Nubank’s color selection highlighted. Since then, other Brazilian fintechs have copied this strategy, such as the fluorescent yellow card from alt.bank, a new-ish Brazilian fintech in a similar space.

To refine its product before public launch, Nubank’s credit card was initially made available only by invitation to friends and family. New members were invited via a referral process, which worked to build immediate credibility. The card only had four requirements: You had to be 18 years of age, a resident of Brazil, registered in the Brazilian tax system and own a smartphone.

Nubank also invented its own credit score to make its card accessible to the unbanked and underbanked population in Brazil. To determine scores, Nubank considers hundreds of variables, including simple things like if a customer reads the contract or just clicks ‘Yes,’ as well as complex behavioral analysis such as when in the payment cycle a customer pays off their credit card bill.

And instead of turning away people who had no credit history, Nubank offered them very low credit and learned from their behavior to offer them more credit over time.

“We had to change the structure of creating the credit score in Brazil, because if you only give a [credit] card to people based on their income, most people aren’t going to be eligible,” said Vitor Olivier, VP of operations and platforms. In fact, for 20% of Nubank’s new customers, this was their first credit card ever.

One of Nubank’s first 10 employees and VP of operations and platforms Vitor Olivier. Image Credits: Nubank

Tough technical trade-offs as the clock ticked

With only months to go before it had to bring its first customers on board, Nubank had to move quickly to sign vendors and build its tech stack. As a credit card, it needed to find a network to join. The team contacted Visa and Mastercard, and since Visa didn’t reply quickly enough, they went with Mastercard.

Nubank co-founder and CTO Edward Wible also had to decide if they were going to build everything in-house or buy ready-to-use software. This was not an easy decision, even with the time pressure.

Typically, software vendors “tropicalize” their products, which means they customize it heavily for Brazil and to comply with Brazilian regulations. “That, to me, is sort of a bad pattern; it makes me nervous,” Wible said. “Most people that buy software don’t really know what they’re buying.”

Nubank co-founder and former CTO Edward Wible. Image Credits: Nubank

He eventually decided to partner with Conductor, a local credit card processing vendor. They also decided to build the remaining products in-house, because getting licensing for some of the other products they needed would take too long and “cost more money than we had in the bank,” he said.

“Waiting for two years to get a license when you’ve taken VC from Sequoia — you’re not going to do that. So that ruled out some possible solutions,” Wible said. “The speed component was fairly important — not speed to perfect, but speed to get started.”

One interesting technical decision that influenced the company’s development was its choice of programming language. While many Silicon Valley startups center around popular languages such as Python or Ruby, Wible chose Clojure as the company’s target environment.

A functional programming language descended from Lisp, Clojure compiles to Java’s virtual machine, which means it’s different enough to require significant investment in training to use effectively.

Clojure logo. Image Credits: Tom Hickey and Rich Hickey, public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Wible, who had a lot of experience with Ruby, says he chose Clojure to build Nubank for its simplicity. “It’s a simple language and it’s designed to make complex things easier. Complexity is what we were trying to fight,” he said. The only problem was that it wasn’t a language that he or many other engineers on the team knew. So as they were building the product, they were also learning the language.

Wible is largely a self-taught engineer, and he describes his strong suit as his ability to learn. “I learned how to learn new things, and how to have the stamina to power through things and flounder and fail and keep going,” he said. Even today, Nubank recruits heavily based on a candidate’s desire and capability to learn quickly.

As if building a technology stack, learning Clojure and putting together a credit card product in a foreign country wasn’t enough, Wible was also learning Portuguese at the time. “Given how stressed we were, and how intensely we were working, the fact that I was able to still go and sit for an hour of Portuguese class, I’m still amazed,” he said. Today, Wible and Velez speak Portuguese fluently with only minor accents.

Investing in users, investing in Nubank

When Nubank’s credit card finally launched, Brazilians’ reactions surpassed everyone’s expectations. It only took three minutes to sign up for a Nubank credit card, and you’d get the card in 3-15 days.

In May 2014, Nubank had its first credit card transaction in beta, around the same time it raised its Series A. Within six months, Nubank had more than 19,000 customers and thousands more on its waiting list.

For the next three years, the company focused on improving the product and growing its market share. By December 31, 2018, Nubank had become a unicorn, over six million people were using its credit card, and 90% of them were active. Revenues that year hit approximately $129 million.

To achieve this dramatic growth, Nubank had to reel in several rounds of funding. About a year after publicly launching its credit card, Nubank raised a $30 million Series B led by Tiger Global. Nubank then went on a fundraising spree, and it seems that raising money would become the least of its worries over the coming years. Just seven months later, the company raised a $52 million Series C, this time bringing on Founders Fund. To date, the company has raised nearly $2 billion in venture capital.

Adding the bank to Nubank

For all its success in building and selling a credit card, emblazoned in its very name was the goal Velez still had his heart set on: Becoming a leading bank.

Nubank’s initial three years served as an opportunity to get a foothold in the market as well as time to generate trust amongst its customers and in the eyes of the Brazilian government.

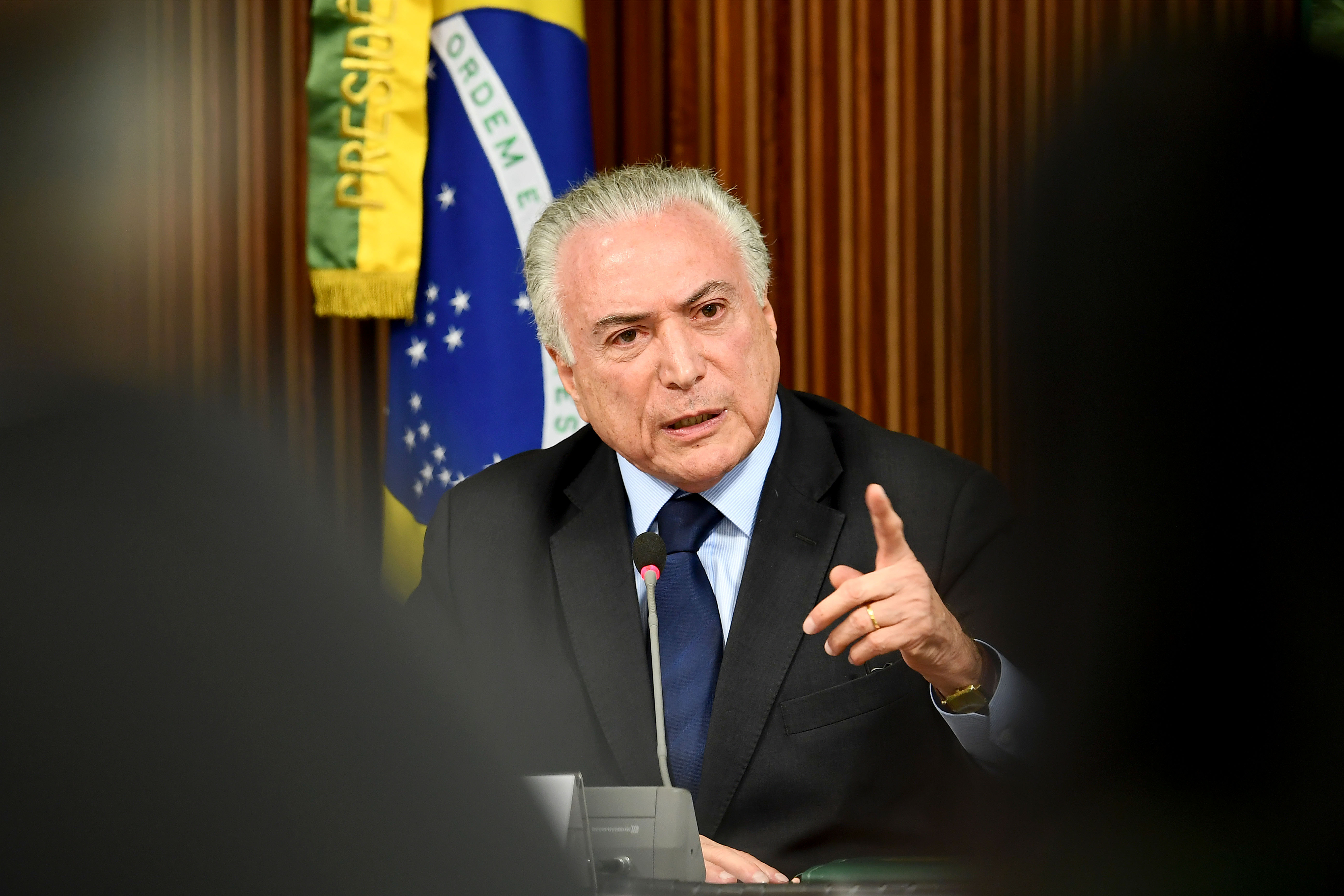

Since the second product would be a more classic bank solution — a savings account — Velez and the team would need to get a presidential decree to get a banking license, as the government prohibits non-Brazilians from investing in or building a local bank.

“Everyone told me that the Central Bank would say ‘No,’ that they didn’t want more competition for Brazil, but I flew to Brasilia to meet with them, and they said, ‘Yes, we would love more competition,’” Velez said.

Former Brazilian President Michel Temer approved Nubank’s application for a banking license in late 2017.

Image Credits: Evaristo SA/AFP via Getty Images

Approval in hand, Nubank again went heads down on development, and in 2017, launched its banking product, NuConta. Translating to “naked account,” Nubank’s savings account was designed to be easy to use right from the get-go.

The product was “ultra simple,” Olivier said. “We’re doing what’s best for the customer, so there’s no need for them to choose [different features].”

Traditional savings accounts in Brazil need the owner to make financial decisions that would be challenging for customers who aren’t financially literate. Instead, Nubank makes those decisions on behalf of its users. For example, Nubank decides the best investment options for its customers’ money instead of asking them what they would like to invest in.

In addition, wire transfers from the account would not be charged any fees, and customers also got daily liquidity, making it easier for them to budget and plan.

It was an offering that worked well for many Brazilians. Take small business owner Alan Pontes, 35, from Rio de Janeiro. He opened his first Nubank account in 2018, leaving behind his previous bank, Bradesco. Three years later, he’s still an extremely happy Nubank customer.

“The other banks are full of fees to do anything. The fees make a big impact. Sometimes I would get really surprised by all the fees that I was getting charged,” Pontes said.

Pontes is talking about how traditional banks package their services in Brazil. To manage an account at one of these banks, customers have to buy a package of services for the month, which includes a certain number of wire transfers, checks and so on. Every time a customer uses one of these services, a credit is deducted from their package, and if they surpass the limit, they get charged overage fees.

Like most other Nubank customers, Pontes decided to use Nubank after hearing good things about it from his friends.

“I started using it and I liked it so much that it became my primary bank,” he says. For Pontes, the selling points were the low fees and the general ease of use, as he finds the Nubank app easy to navigate. “With my old bank there were a ton of buttons on the app, but I really only had to use two of them.”

Just like its credit card, NuConta was a resounding success. Brazilians loved the simplicity Nubank baked in, and they stayed for the stellar customer service and the lack of exorbitant fees. By 2019, Nubank had 10 million customers and had raised a total of $962 million. It also expanded its office geographically, having opened a tech office in Berlin.

The Disney of banking, minus some blemishes

Pontes seems to be Nubank’s prototypical customer, and like the bulk of its customer base, word-of-mouth brought him to its door. The company prides itself on having a $0 customer acquisition cost (CAC), which is extremely rare for a fast-growing and scaling startup — if we can still call it a startup.

In lieu of marketing, Nubank focused on providing incredible customer service. “We over-invested in customer service experience in large part because we didn’t have physical branches,” Wible said.

Considering the bar was so low at other institutions, it seems Nubank simply had to focus on getting the basics right, he noted. “Do the right thing, act like a human, be nice — which is the opposite of what people were doing in the market back then.”

But even this storied customer service hasn’t converted everyone. Fernanda Freitas, an in-house counsel for a luxury fashion conglomerate also based in Rio de Janeiro, says that for her and others of means, the online experience of the existing banks works just fine.

“These online banks appeared, and I didn’t really have a reason to change,” she said. “Today, I don’t have to pay fees because I maintain investments in both of my banks,” she added. For most Brazilians though, the monthly service package can get very expensive quickly. For example, Freitas pays R$85 (about $17) every month to Bradesco for one of her accounts.

“The advantage of these online banks is that you don’t have to have income or credit to get a credit card,” she said. “I see these online banks for people who don’t have access to a traditional bank.”

This would explain why Nubank’s demographic is largely people between the ages of 18-35 who make about R$1,000 to R$5,000 a month ($200-$1,000 USD), according to a case study by Harvard Business School.

However, its stellar customer service hasn’t insulated Nubank from backlash when things go wrong, though.

In August 2020, NuConta customers said money had suddenly gone missing from their accounts. Soon, Twitter, social media and websites were flooded with messages saying, “Nubank, return my money!” in Portuguese.

Apparently, some NuConta users found their accounts had inaccurately low balances, due to some errors on state-owned bank Caixa Econômica Federal’s system, according to Nubank. The company soon restored its customers’ balances, but Olivier remembers it being a trying time for Nubank. In the long term, though, this seems to have had little effect on people’s trust in the company.

Nubank’s offerings have proliferated since it launched its banking service. It now offers a debit card, peer-to-peer payment via Pix (the Brazilian equivalent of Zelle), loans, rewards, life insurance, and an account and credit card for small business owners, in addition to its original credit card offering for individuals.

The company has its eyes on geographical expansion as well. By 2020, Nubank had made its debut in Mexico and came out of beta that spring, mirroring its strategy in Brazil by launching just a credit card. It has also entered Colombia, and the product is still in beta there, with about 3,000 people testing the credit card and another 300,000 on the waitlist.

But geographic expansion isn’t the only priority for Nubank. As we’ll see in part four of this EC-1, Velez has plans to disrupt even more verticals with the same zeal for customer service and viral features.

Nubank EC-1 Table of Contents

- Introduction

- Part 1: Origin story

- Part 2: Co-founder dynamics

- Part 3: Launching and scaling

- Part 4: Market expansion and future

Also check out other EC-1s on Extra Crunch.