An unprecedented flood of citizens concerned about net neutrality is what took down the FCC’s comment system last May, not a coordinated attack, a report from the agency’s Office of the Inspector General concluded. The report unambiguously describes the “voluminous viral traffic” resulting from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight segment on the topic, along with some poor site design, as the cause of the system’s collapse.

Here’s the critical part:

The May 7-8, 2016 degradation of the FCC’s ECFS was not, as reported to the public and to Congress, the result of a DDoS attack. At best, the published reports were the result of a rush to judgment and the failure to conduct analyses needed to identify the true cause of the disruption to system availability. Rather than engaging in a concerted effort to understand better the systematic reasons for the incident, certain managers and staff at the Commission mischaracterized the event to the Office of the Chairman as resulting from a criminal act, rather than apparent shortcomings in the system.

Although FCC leadership preemptively responded to the report yesterday, the report itself was not published until today. The OIG sent it to TechCrunch this morning, and you can find the full document here.

The approximately 25 pages of analysis (and 75 more of related documents, some of which are already public) relate specifically to the “Event” of May 7-8 last year and its characterization by the office of the Chief Information Officer, at the time David Bray. The investigation was started on June 21, 2017. The subsequent handling of the event under public and Congressional inquiry is not included in the scope of this investigation.

As the report notes, Bray shortly after the event issued a press release describing the system’s failure as “multiple distributed denial-of-service attacks.” A variation on this was the line going forward, even well after Bray left in October 2017.

However, internal email conversations and analysis of the traffic logs reveal that this characterization of the event was severely mistaken.

Here it ought to be said that in the chaos of the moment and with incomplete time and information, an accurate diagnosis of a major systematic failure is generally going to be an educated guess at first — so we mustn’t judge Bray and his office too harshly for its mistake, at least in the immediate aftermath.

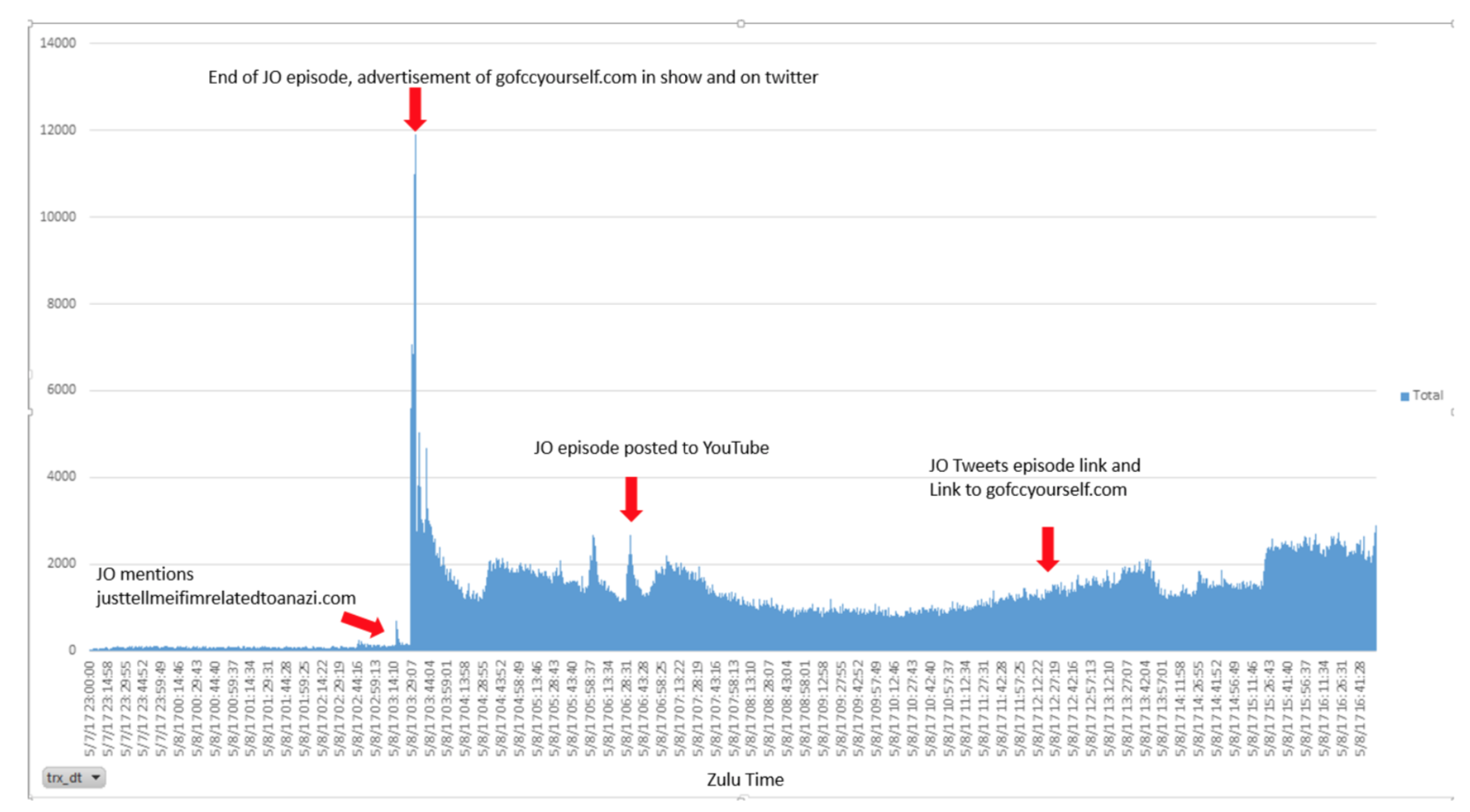

But what becomes clear from the OIG’s investigation is that the DDoS narrative first advanced by Bray is not backed up by the evidence. Their own analysis of the logs clearly shows that the spikes in traffic correlate directly with activity from John Oliver’s Last Week Tonight, which that evening and the following morning posted tweets and videos that garnered an immense amount of traffic and directed it at the FCC’s comment system.

Chart showing traffic spikes correlating with John Oliver (JO) related events.

“These spikes in traffic are singular rather than sustained, that is, the unique IP addresses that visited the FCC domain and ECFS did not do so over a sustained period of time, at regular intervals (as would be expected during a DDoS),” the report explains in the caption for the graph above.

“The traffic observed during the incident was a combination of “flash crowd” activity and increased traffic volume resulting from [redacted] site design issues,” reads the report. I’ve asked for more detail on these design issues and how they contributed to the system’s failure.

Interestingly, it appears some at the FCC were aware that Oliver was planning a segment on net neutrality for that time period, but no one thought to brace for it. According to a colleague interviewed for the report, “Bray was furious that he had not been informed about the John Oliver episode.”

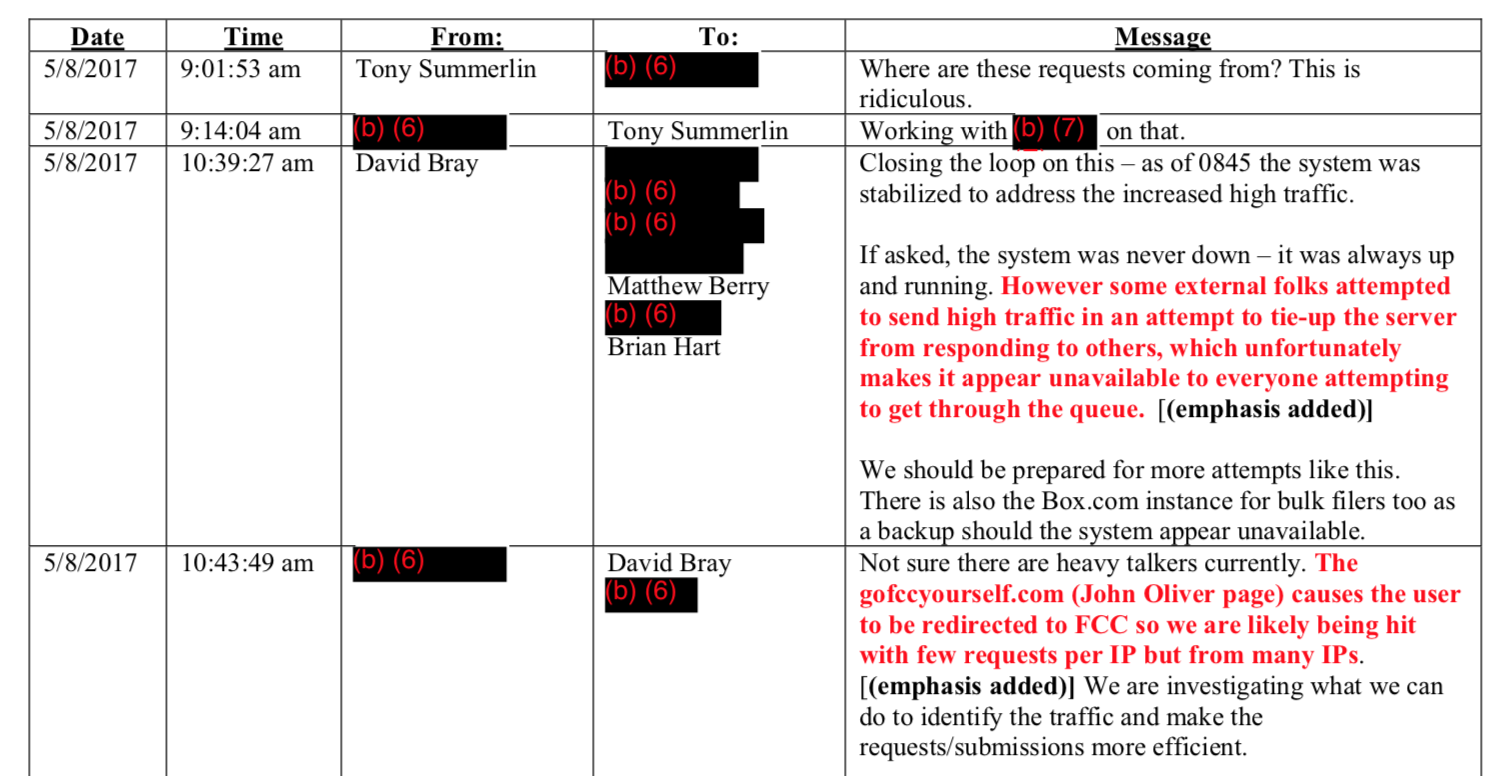

Email excerpts from the time of the event, collected by the FCC’s OIG.

In fact, however, even confronted with the fact that Oliver’s segment was likely directly driving traffic, Bray suggested that “trolls” and 4chan were the more likely culprit.

We’re 99.9% confident this was external folks deliberately trying to tie-up the server to prevent others from commenting and/or create a spectacle.

Jon Oliver invited the “trolls” – to include 4Chan (which is a group affiliated with Anonymous and the hacking community).

His video triggered the trolls. Normal folks cannot manually file a comment in less than a millisecond over and over and over again, so this was definitely high traffic targeting ECFS to make it appear unresponsive to others.

All this, and the description put in the press release and some subsequent communications, is “not accurate,” as the OIG put it.

As a result, “we determined the FCC, relying on Bray’s explanation of the events, misrepresented facts and provided misleading responses to Congressional inquiries related to this incident.”

It’s worth noting that this has already been looked at by federal prosecutors:

Because of the possible criminal ramifications associated with false statements to Congress, FCC OIG formally referred this matter to the Fraud and Public Corruption Section of the United States Attorney’s Office for the District of Columbia…On June 7, 2018, after reviewing additional information and interviews, USAO-DC declined prosecution.”

In a way, as Chairman Ajit Pai wrote yesterday, this does somewhat exonerate his office for its year-long campaign of stalling, half-truths, and outright refusals to answer questions. If they took Bray’s characterization as gospel, they had to stick to that analysis. Furthermore, with an investigation ongoing, what they could and couldn’t say was likely limited at the request of the OIG.

But that’s only a partial pardon. In the year and change since the event there has been ample time for reflection and revisiting of the data. Bray left in October; why did the new CIO not use the occasion to take a fresh look at a report that was plainly doubted by many in the agency?

The CIO’s office, as the report notes, never actually issued a substantive report showing that its DDoS narrative was true. And shortly after the event, it was, as one staffer put it, “common knowledge” that the analysis was flawed. This knowledge was arrived at through “further research” after the fact — but then it turned out no “further research” was conducted.

What kind of operation is this? Why was FCC leadership not foaming at the mouth asking for better information? The Chairman was under fire from all sides — no one bought the story he was selling — why not walk over to the CIO’s office, now rid of its Obama administration–tainted head (Pai mentioned this association twice in his statement yesterday), and demand answers?

Pai denies that he or his office was aware of these shortcomings and opted not to rectify them because they were advantageous to his plan to reverse 2015’s net neutrality rules. But how could such a demonstrably shoddy and undocumented analysis persist for so long, under such close scrutiny? This wasn’t a minor technical glitch unworthy of leadership’s attention. It was national news.

The optics of a confusing and incomplete DDoS report aren’t good. But the report, if it was wrong, as everyone seemed to consider it even day-of, could always be disavowed and its author blamed on Obama.

What’s worse are the optics of a wave of public opposition to a controversial proposal, so strong that it literally took down the system created — and recently upgraded! — to handle that kind of feedback. This narrative, of a flood of pro-net-neutrality commenters so large that not only did it break the system, but many of their comments were arguably unable to be posted and (notionally) included in the FCC’s analysis — that, my friends, is a bad look.

Although this investigation has concluded, another by the Government Accountability Office is ongoing and may have a wider scope. If not, however, it seems unthinkable that the FCC and its current leadership can walk away from this unscathed. Ultimately this entire debacle took place under Ajit Pai’s watch, and his handling of it is at best dubious. Citizens and no doubt elected officials are almost certain to ask hard questions — and this time, the Chairman might actually have to answer them.