Attorneys for Oracle and Google presented their closing arguments today in a lawsuit over Google’s use of Java APIs owned by Oracle in Android. Oracle accused Google of stealing a collection of APIs, while Google suggested that Android transformed the smartphone market and Oracle sued out of desperation when its own smartphone attempts failed to launch.

The case is expected to have sprawling impacts on the software industry. If the jury finds that Google did indeed steal code from Oracle, it could disturb the way engineers at small startups build their products and expose them to litigation from major companies whose programming languages they use.

Before sending the jurors home last week, presiding Judge William Aslup joked that they should not look up what an API is online over the weekend. It was a lighthearted instruction meant to caution jurors against doing their own research in the case, but struck at a fear that’s probably plaguing both legal teams — what if the jury still doesn’t understand the technology at the heart of the case?

At issue in Oracle’s lawsuit is whether or not Google’s implementation of 37 Java APIs in Android was fair use. Google has argued that Sun Microsystems, which created Java, always intended for its programming language and accompanying APIs to be used freely. Oracle purchased Sun in 2010 and claimed that Sun executives believed Google had infringed their intellectual property and simply hadn’t brought legal action.

An appeals court has already decided that the Java APIs in question are copyrightable. This case, which has stretched over two weeks in a district court in San Francisco, aims to determine whether Google’s implementation of the APIs can be considered fair use. Beginning this afternoon, the jury will consider several factors — most importantly, whether Google transformed Oracle’s code when it built Android, and whether the introduction of Android harmed Oracle’s business.

Harry Potter or hamburger

Before the two tech titans can clearly argue whether Google’s use of the APIs was fair, they need to agree on how to explain APIs to their lay audience in the jury box — and they haven’t done that. Even as Oracle and Google’s legal teams laid out their final arguments today, they bickered over how best to describe an API.

Google’s witnesses and lawyers offered a litany of explanations for APIs. Google attorneys recycled a filing cabinet analogy from the first round of Oracle v. Google, in which they compared the packages, classes and methods contained within the Java API library as cabinets, drawers and individual manila files.

Other witnesses for Google entertained their own comparisons: Jonathan Schwartz, the former CEO of Sun, explained APIs by comparing them to hamburgers. Many restaurants have the word “hamburger” on their menu, he said, but the recipes — in the world of APIs, the implementations — are unique. Other witnesses sought to compare APIs to such ubiquitous items like wall outlets and the gas pedals of cars. No matter the comparison, the point was the same: Google never expected that its use of something so common would become so contested.

In a bid to portray APIs as a creative endeavor worthy of strong copyright protection, Oracle’s lead attorney, Peter Bicks, compared them to Harry Potter novels, saying the packages, classes and methods could be understood as the series, books and chapters.

This is what this case is about: a company that believes it is immune to copyright laws. You don’t take people’s property without permission and use it for your own benefit. Oracle attorney Peter Bicks

“Why are we looking at Harry Potter?” Google’s lawyer Robert Van Nest fired back during his closing argument. “This isn’t about Harry Potter. This is not a novel; it’s not a book. They want to talk about Harry Potter rather than what the labels do.”

It’s not clear whether the jumble of popular novels and lunch items clarified APIs for the jurors or merely confused them. But it’s obvious that everyone else in the courtroom, from the attorneys to the judge, is concerned that the jurors won’t understand what APIs are or how they work — in a rare moment of agreement, Oracle and Google attorneys allowed the jurors to take their notebooks home over the weekend so they could study up.

“Java was there first”

In his closing remarks, Bicks argued that Java formed the foundation of the smartphone market before the introduction of Android. Google engineers faced immense pressure to rush Android to market, in Bicks’ telling, and they took shortcuts to get there, which led to them ripping off the 37 Java APIs.

“This is what this case is about: a company that believes it is immune to copyright laws,” Bicks said of Google, adding, “You don’t take people’s property without permission and use it for your own benefit.”

Bicks staked his case on several embarrassing internal emails between top Google employees. He revisited one 2010 exchange that Oracle has often referenced as a smoking gun, in which Google engineer Tim Lindholm told Android team leader Andy Rubin that the alternatives to Java “all suck” and noted, “We conclude that we need to negotiate a license for Java.”

Another email Rubin received from a team member fretted that Android hadn’t created a strong enough competitor to Java’s class libraries. “Ours are half-ass at best,” Google engineer Chris Desalvo wrote. “We need another half of an ass.”

Bicks argued that the internal messages show Google didn’t believe that its use of the Java APIs was fair or legal, but that the company’s engineers moved forward anyway out of sheer desperation.

In doing so, Bicks said Google devastated Oracle’s market. “Java was there first,” he said over and over, emphasizing the use of Java in feature phone operating systems like SavaJe and Danger and claiming that, prior to the introduction of Android to the market in 2008, almost all smartphones were running some form of Java. (The iPhone, which runs on Objective-C and was introduced in 2007, is a notable exception.)

Not only had Java cornered the market, Bicks claimed, Android wasn’t as radically different as Google claimed. He presented a side-by-side comparison of the HTC Touch Pro, which ran Java, and the HTC Dream, which ran Android, as proof — and there’s no denying that the two phones look remarkably similar.

Bicks said that once Google offered Android as a free and open source operating system, Oracle’s options for licensing Java were slashed. Their market crumbled, Bicks said, citing testimony from Oracle co-CEO Safra Catz in which she claimed she gave Amazon a 97.5 percent discount to license Java in order to prevent the retailer from building its Paperwhite reader on Android.

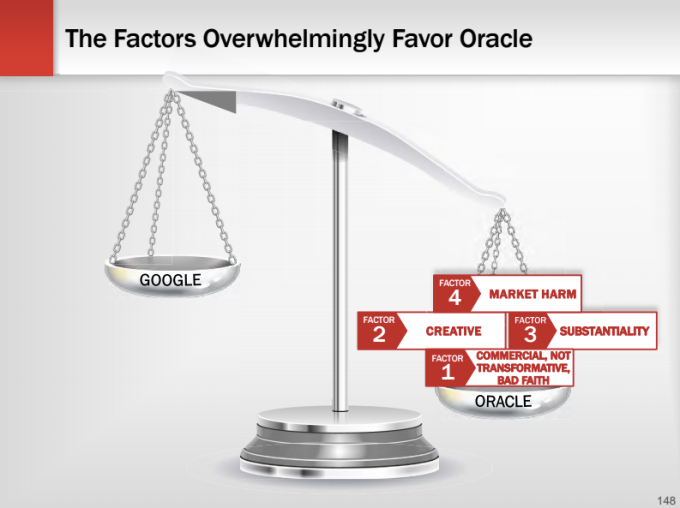

As he rolled through the four legal measures of fair use, Bicks kept returning to a graphic showing the scales of justice. As he discussed each measure, it slowly descended into Oracle’s side of the scale, tipping justice ever further in Oracle’s favor.

Oracle slide shown to jury during closing arguments.

Near the end of his presentation, Bicks showed a slide of the form the jury will use to indicate whether it has ruled in favor of Oracle or Google, with a bright red X marking Oracle as the victor.

“It takes somebody with strength and courage to stand up to somebody like Google, and that’s what Oracle has done,” Bicks said.

“The whole market has changed and you haven’t changed with it”

During his closing argument, Google’s Van Nest characterized Oracle as a sore loser in the battle for corporate dominance. Android took over the smartphone market because it was a superior product to Java phones, not because it used the 37 Java APIs in question, he said.

“Android is exactly the kind of thing that the fair use doctrine was intended to protect,” Van Nest told the jury. He pointed out that Android transformed Java SE for use in smartphones when it had traditionally been used only in desktop computers and servers, and noted that, although Oracle made several attempts of its own to develop a smartphone with Java SE, they all failed. (It’s worth mentioning here that I worked briefly as a contractor with Google prior to joining TechCrunch, although my work was not related to Android and I had no contact with the Android team.)

Van Nest claimed Oracle was preoccupied with the so-called feature phone market while Google was leaping ahead to the smartphone era, creating a product Oracle couldn’t have imagined or built on its own. Android changed everything, Van Nest argued. However, he claimed that Android’s dominance in the smartphone market had a positive effect on Oracle’s business by keeping Java relevant to the modern developer community.

“The whole market has changed and you haven’t changed with it,” Van Nest said. “Android is the number one thing keeping Java out there, doing as well as it is.”

Sun and Google executives both understood that Google’s implementation of Java in Android constituted fair use, years before Oracle finalized its purchase of Sun in 2010, according to Van Nest. He claimed that, even after Oracle took over Sun, it did not target Google immediately and in fact welcomed Android as a beneficial addition to the industry.

The Java APIs were always intended to be used freely by anyone, Van Nest insisted, because doing so would promote the growth and popularity of Java. “Oracle had no investment, none of the risk. Now they want all the credit and a whole lot of money. That’s not fair,” Van Nest said.

Van Nest also emphasized that Android engineers had only reimplemented a sliver of Java’s code rather than copying from it liberally. They took very little and radically altered what they did take.

Android is exactly the kind of thing that the fair use doctrine was intended to protect. Google attorney Robert Van Nest

Despite the internal Google emails harped on by Oracle, Van Nest said that the company never imagined it was infringing on Oracle’s intellectual property — and adamantly denied any infringement when Oracle finally brought it up in the summer of 2010.

“We will not pay for code that we are not using, or license IP that we strongly believe that we are not violating, and that you refuse to enumerate,” a former Google computer scientist, Alan Eustace, wrote in a June 2010 email to Catz. Oracle sued two months later.

In closing, Van Nest attempted to appeal to the jury’s Bay Area roots by highlighting the tech industry’s history in the area. “We are number one in the world on innovation,” Van Nest said in reference to Northern California. Android, he added, “is the kind of innovation that comes along once in a lifetime.”

The jurors will consider the case this week. Whatever their verdict, the case will probably be appealed — with $9 billion on the line, neither side is likely to go down without a fight. However, Oracle declined to comment when asked if it would appeal. Google did not return a request for comment.