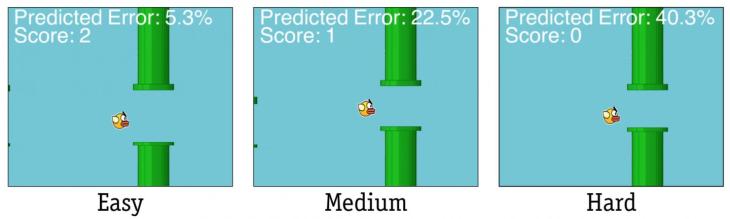

I know we’re supposed to be all done talking about Flappy Bird, but I think it’s justified to bring it up when it appears in a research paper about why games like Flappy Bird are so hard — and so frustrating. Turns out the controls are fundamentally bad.

That may not come as a surprise to — well, anyone. Angry Birds and Neko Atsume work fine, but action games on mobile tend to suffer from unresponsive controls. And it turns out you can only blame the developer so much.

Researchers at Aalto University in Finland, probably after dying for the 10 millionth time in Flappy Bird and pledging to find a way to justify their failure scientifically, show in a new paper that a number of factors combine to make controls unreliable.

“We can finally explain why games that require accurate timing are annoyingly hard on touchscreens,” said co-author Antti Oulasvirta in a news release accompanying the paper.

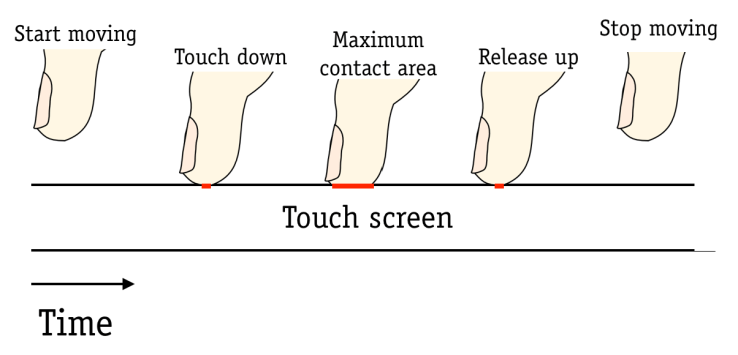

First: “users cannot precisely control how high they hold their finger,” which isn’t the case with a physical button, something you maintain physical contact with. This introduces variability in timing.

Second: “the timing of the sensor event is uncertain.” A player can’t reliably tell when the touchscreen will actually register a touch. Is it when the finger makes the slightest contact? Is it when it passes some other threshold? Further variability is introduced.

Third: latency is unpredictable within games and apps. Sometimes a registered touch will take effect quickly, sometimes not — depending on a number of factors, only some of which are under the control of the game designer. More variability!

There are some solutions: minimizing and regularizing latency, for one thing, is always a good practice. And by making touch events only take place at a certain “touch-maximum” threshold, reliability and accuracy were increased and error rates dropped by 9 percent. As for finger height — unfortunately, there doesn’t appear to be a solution for that.

At least we’ve got a better handle on the problem. For now, stick to real buttons when you can.

The paper, by Oulasvirta and Byungjoo Lee, will be presented at the Association for Computing Machinery’s Computer-Human Interaction conference next month.