Platforms are what make the technology world go ’round. Great platforms create value for technologists everywhere — be it a technology-specific platform like what Google has newly open-sourced through Tensor Flow, a customer-specific platform development environment like Salesforce or a truly horizontal platform like what Amazon offers through AWS.

This value stems from the fact that platforms enable new waves of innovation by reducing friction in the process of building new solutions. In an era before a platform technology like iOS was created, anyone wanting to build a mobile application would have to create everything from the app to the software that guides user interaction. Once the platform is in place, any number of innovators can strike out to build products and services to change the world — without recreating the foundation.

This much, at least, is pretty well understood. What’s less well understood is what makes a platform most interesting as a business. Which platforms will create profit and which will struggle. Because investors spend so much of their time looking at these businesses, we tend to have a sense for the biggest challenges that lay in front of platform innovators. And often, we look for three types of platforms that can yield exciting businesses.

Not all platform builders are setting out to create companies. But those that do can think about building these three types of platforms as a framework toward sustainability.

Platforms that monopolize the market

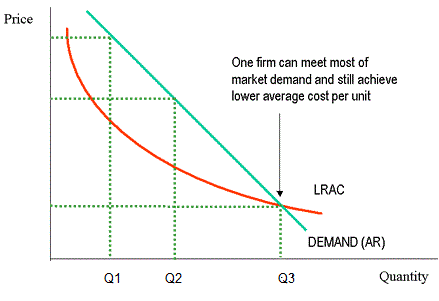

For many companies building platforms, scale can be a powerful tool to protect the business. Sometimes, only scale can provide producers the price efficiency to win any customers at all.

Large businesses can be built when platforms require scale to deliver value to their users. Consider the electric grid. Whether it’s for light bulbs, refrigerators or computers, endless amounts of our livelihoods depend on the grid’s current.

Atop the grid, a century of innovation occurred. But despite its criticality, in a given market there is typically only one grid. Why? Because to power any one house requires a power plant and miles of wiring. But it simultaneously doesn’t make a lot of sense to lay every wire twice.

All else being equal, monopoly platforms tend to make for good businesses.

My favorite outlandish example of this type of platform can be found in SpaceX. Most people think of rockets when they think of SpaceX (and they should). But beyond simply launching metal objects into the abyss, SpaceX has actually created a fairly robust platform for space innovation. By making access space available at relatively low prices, an ecosystem of companies have received cheap access to the skies. Companies like Nanorack or Planet Labs can only exist because someone offers them a rocket platform to get to space.

Getting any satellites at all into space requires substantial scale. Investment in a physical rocket needs to be spread across a number of private payers; different satellite companies and governments paying their way for a ride to low-earth orbit. Research and development dollars need to be amortized across a fleet of rockets.

So it only makes sense for a company to serve these markets if it can launch many similar payloads into space. And there is every incentive for vendors to price their trips to space low enough that they can increase the volume of demand and amortize their R&D across a larger and larger array of rockets. Ultimately, that pricing minimizes the amount of new entrants into the ecosystem.

That’s why SpaceX’s platform is so well positioned. Access is granted for innovators at low cost. But the incentives for at-scale competitors to enter the market is quite low.

The alternate example can be found in CubeSat companies. Every year, microchips get smaller, sensors get more powerful and the hardware that’s floating around in space can be rather easily improved. For thousands, not millions, of dollars, the next generation of weather-sensing arrays can both be built and grab a spot on one of SpaceX’s next flights.

The low cost to build and standard designs of CubeSats make it (relatively) easy to recreate these sensor networks in the sky. Despite the fact that there is a wealth of opportunity to innovate atop their data, it’s not clear that the companies deploying these arrays will be able to maintain margins as more vendors enter the market.

From an economist’s perspective, the best way to categorize the types of platforms that generate value by being the only game in town are as monopoly or oligopoly markets. In most naturally occurring monopoly or oligopoly markets, the scale benefits of production make it uninteresting to have a plethora of players. With just a few players operating at scale, it’s possible to serve the needs of an entire ecosystem at the lowest prices. (This can be slightly different for open-source communities.)

Now, it’s important to note that these types of platforms don’t last indefinitely. As we’ve seen with the transition from on-premise computing to the cloud, major technology or architectural changes can very quickly undermine the position of platform providers. But all else being equal, monopoly platforms tend to make for good businesses.

Platforms with network effects

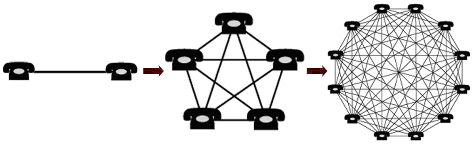

LinkedIn is a great business. The reason extends far beyond the rapid revenue growth that the company has experienced recently. One of the biggest drivers of the company’s success is the strength of its network effect. Every time a new member joins LinkedIn’s community of professionals, the membership benefits. As the network grows, the value of the network increases for each user.

What’s even more phenomenal for LinkedIn is that the value of the network is derived almost entirely through indirect connections. While you can easily convince your closest six friends to ditch Skype in favor of WhatsApp, it’s next to impossible to convince all your future sales leads or company recruits to leave LinkedIn for the next shiny new platform. Because LinkedIn’s most important members are the ones you don’t yet know, the strength of the network effect is incredibly powerful. That makes LinkedIn’s platform very sticky (disclosure: I am a LinkedIn shareholder).

With such a sticky initial product, LinkedIn can continue to ask for more data or privileges from users as it grows, knowing the likelihood that they’ll leave is ever diminishing. With each new requirement, the company’s ability to build new products grows; increasing the potential of LinkedIn’s data as a platform for innovation and the amount they can charge their ecosystem members.

Platforms that build network effects over time are powerful, sticky and hard to displace.

The same type of platform strength can be seen in companies like Apple and Google, as more and more developers turn to their smartphone and watch platforms to develop applications. As the number of developers and applications grow within ecosystems, users like you and I derive great value from those networks — making the likelihood that we’ll leave ever smaller — meaning that, over time, Apple and Google can charge more of us to use their systems.

Platforms that build network effects over time are powerful, sticky and hard to displace. Even in the case of technology changes, these types of platform providers are often able to catch up because of the sheer advantages that adoption can lend them. Their builders may not be able to generate lofty revenues early, but over time they’re quite capable of creating profitable businesses.

Platforms with proprietary assets

While some companies differentiate their platform positioning through elegant strategies of scale and network effects, others simply offer proprietary assets. This is less frequent in a world of open-source innovation, but very much still there. The easiest way to think about this is with intellectual property (IP) protection.

Consider Magic Leap, the Google-backed company building a system that projects light directly into your retina to deliver virtual and augmented reality. The technology that Magic Leap is likely to deliver to its ecosystem is likely to be heavily protected by patents and trade secrets. If the difference between their solution and others’ technology is large, people will pay to have access to that proprietary technology.

But in the world of technology, IP isn’t the only proprietary asset. And, in fact, in a world with increasing levels of open-source infrastructure, IP tends to be less a driver of platform advantage than you’d imagine. But proprietary assets still abound — more often today in the form of proprietary data.

It’s critical that innovators trying to build platform companies deliver value in ways others can’t emulate.

Salesforce1 is a wonderful example of a strong platform built atop a proprietary asset: customer data. The way Salesforce’s CRM system was architected enabled developers to easily build applications that could pull from a company’s underlying customer tables.

Marketo, ExactTarget and HubSpot could reach down into Salesforce and pull out information about contacts, buying history and relationship owners. Because this customer information stored in Salesforce’s cloud is so critical to any number of SaaS companies, Salesforce was able to build a very successful platform with it. Salesforce could extract large taxes, even without the most advanced technology or friendliest developer environment.

Creating a platform is a powerful way to deliver value to the economy. But delivering value to the economy isn’t enough to create value for investors and entrepreneurs. To do that you have to capture value as well. It’s critical that innovators trying to build platform companies deliver value in ways others can’t emulate.

For platforms that monopolize markets, certain companies win because the market can’t support multiple platforms. For platforms with network effects, certain companies win because customer value creation compounds exponentially. For platforms with proprietary assets, platforms win because they offer something no one else can — because they’re the only ones that have access to it.