Building a drone’s hardware and software from scratch is tough and expensive, but open source drone kits are inflexible. So to power businesses looking to customize drones for commercial uses from agriculture to industrial inspections, Airware has raised a $25 million Series B led by Kleiner Perkins. The money will fund the launch of Airware’s drone operating system later this year, including autopilot hardware, navigation, software, and cloud infrastructure for storing and analyzing data from a drone’s sensors.

Kleiner’s Mike Abbott will join the board, and previous investors Andreessen Horowitz and First Round Capital are also in on the raise that brings Airware to $40 million in funding. That gives it plenty of money to hire sales, marketing, support, and engineers in anticipation of Airware’s drone OS coming out of beta and into the market.

When I visited Airware’s office at laboratory this week, the company’s rapid ascent took me by surprise, until I realized founder Jonathan Downey‘s parents were both pilots.

Getting Off The Ground

Airware Founder and CEO Jonathan Downey

Downey was literally born to change the skies. Grandpa flew planes. Uncle and cousin did too. Dad was mom’s flight instructor. “Pilots who begat pilots who begat pilots”, Jonathan laughs. He learned to man a cockpit while young and even flew commercial airliners.

At MIT he started a student club to build a drone for an intercollegiate competition, where he realized that open source drone frameworks were too rigid for repurposing to specific functions. Downey went on to build autonomous helicopters for Boeing, discovering the intense monetary and engineering resources necessary to build drones. He figured that if he could build a safe, reliable, flexible drone platform, other companies would pay to avoid worrying about the basics and concentrate on the customizations they need.

And so Airware was born. After running the company by himself for a while, in 2012 he started poaching Boeing hardware, software, and flight control engineers. Airware joined the Winter 2013 Y Combinator class and picked up a $3 million seed led by Google Ventures, though at the time Airware seemed like it might be ahead of its time. Soon enough, though, interest in drones took off, so Airware raised a $12.2 million Series A led by Andreessen Horowitz and added its partner Chris Dixon to the board.

Airware then focused on proving that drones can be more than war machines. It sent a team out to the Ol Pejeta black rhino sanctuary in Kenya to test how drones could be used to monitor wildlife populations and intrusions by poachers. Airware wrote how “The drone, equipped with Airware’s autopilot platform and control software, acts as both a deterrent and a surveillance tool, sending real-time digital video and thermal imaging feeds of animals – and poachers – to rangers on the ground using both fixed and gimbal-mounted cameras.”

Ready To Fly

The last six months have been centered on working with drone manufacturer beta partners Delta Drone and Cyber Technology to get the final kinks out of its commercial platform. When drone software crashes, it really crashes, so reliability is top of mind for Downey’s team as it gets ready to sell its vertically integrated platform to the 600 drone manufacturers out there.

Downey tells me that Delta was one of many companies that tried to develop full-stack drones in-house after getting frustrated with open source options. But he says they soon found building every aspect of a drone was “hard, expensive, and a distraction from customer needs”.

Airware will take on that engineering challenge for other companies. Having Mike Abbott from Kleiner on the board should be a big help. Downey tells me he was especially excited about Abbott joining Chris Dixon and him on the board because “He was the VP of engineering at Twitter who grew it from 80 to 350 engineers in 18 months” and brought the company out of its failwhale phase. Abbott had also been in the trenches running startups building products as platforms.

After the commercial launch in 2014, Downey tells me Airware will continue to expand the capabilities of its platform, though most of that will be in added compatibility and partnerships with third-party drone manufacturers. “We’re really enabling an ecosystem. We believe that with such a variety of use cases and manufacturers, it really needs an ecosystem of companies to provide all the value.”

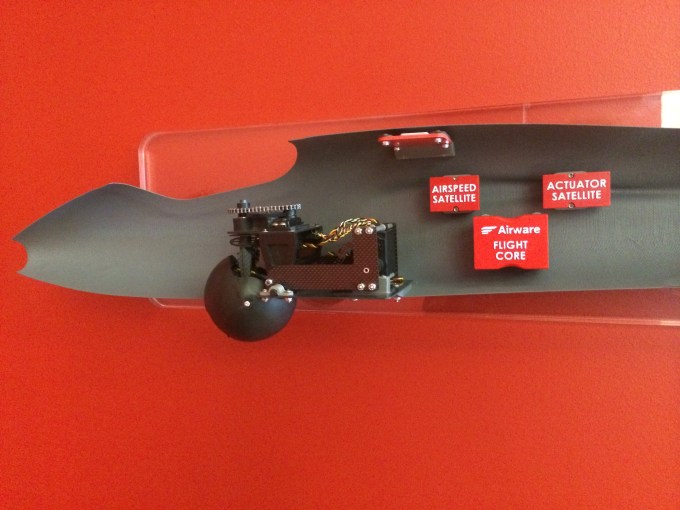

Director Of Customer Implementation shows me the UASUSA Tempest in the Airware integration room

Airware’s doing everything it can in its own laboratory though. Beneath its office in San Francisco’s SOMA district, Director of customer implementation John Kolaczynski showed me around “the integration room”. The garage featured several of the drones Airware works with, from the parachute-landing Delta Y model to the UASUSA Tempest, a bigger winged drone you launch from a bungee cord and that lands on its belly.

To test Airware’s flightcores, the company has a giant machine called an Ideal Aerosmith. A horizontally rotated platter inside a vertically spun chassis pumped full of liquid nitrogen lets Airware test its hardware in any temperature or flight angle. Inside a caged enclosure, Airware keeps more drones, including some from its competitors. Supposedly the fence is to keep track of the drones and make sure no one steals them, but Kolaczynski joked “if they ever become sentient, we know they’re in the cage.”

Drones locked inside the security cage in Airware’s integration room

More Than War Machines

Airware is eagerly anticipating the release of new drone regulations later this year about where drones can be flown, at what altitudes, what sizes of vehicles, and what standards the operators and aircraft have to meet.

Downey tells me “Sometimes people ask me what are my worries about regulations from the FAA. My worries are really about there being no regulations at all because otherwise there will be a lot of bad actors operating in ways that are not reliable and safe.” He knows that it will only take one commercial drone crash that hurts or kills a human to trigger a backlash against the industry. The public is already a bit iffy on drones, which is why “reliable and safe” was the phrase Downey used most during our interview. He peppered it into most sentences where he mentioned the word drones.

Downey tells me “Sometimes people ask me what are my worries about regulations from the FAA. My worries are really about there being no regulations at all because otherwise there will be a lot of bad actors operating in ways that are not reliable and safe.” He knows that it will only take one commercial drone crash that hurts or kills a human to trigger a backlash against the industry. The public is already a bit iffy on drones, which is why “reliable and safe” was the phrase Downey used most during our interview. He peppered it into most sentences where he mentioned the word drones.

Alternatively, Downey fears that if there is stringent regulation that is too focused on paperwork, it could favor giant conglomerates of the aerospace industry and make it tough for startups like Airware to thrive. He tells me “if the regulations are too restrictive, people will either ignore them to an extent, or use the technology internationally, which will apply pressure to go back and make sure the regulations are reasonable.” Since so many of Airware’s customers are overseas anyways, he says the FAA can’t keep it down.

Drones aren’t inherently killing machines. It’s all about how you use them, Downey explains. “I think this is a technology similar to GPS, which was originally developed by the military largely for weapons guidance. If you asked 15 years ago if [people would be] willing to carry a GPS tracking device in their pocket they would have said ‘absolutely not’.” Now we all have them.

Downey concludes, “The more that drones are being used for anti-wildlife poaching, increasing crop yields, and decreasing the use of fertilizers and pesticides, I think people will grow increasingly comfortable with this technology coexisting with them in their everyday lives.”