Earlier this week, Facebook announced that it had acquired Oculus VR for $2 billion, and it turns out that this isn’t the only recent piece of M&A in the category of head-mounted wearable computing. Microsoft, we have discovered, has paid up to $150 million to buy IP assets related to augmented reality, head-borne computers, and related items from the Osterhout Design Group, a low-profile company that develops wearable computing devices and other gadgets, these days primarily for the military and other government organizations.

As you might remember, we first broke the news that Microsoft was looking at acquiring ODG, or part of its assets, in September 2013, at a price tag of up to $200 million, depending on what went into the deal.

Here’s what ended up happening: Microsoft was indeed in discussions with the company, and as we reported, the conversations were focused around whether Microsoft would try to buy the whole company outright or just intellectual property. Ultimately, it worked out to be the latter, for a price that TechCrunch understands is between $100 million and $150 million.

After a source told us that the deal was done, we dug a bit further and managed also to get a confirmation from Ralph Osterhout himself, the low-profile inventor, founder and head of ODG.

While he would not talk about any of the terms of the transaction (we got a price from another source), he tells me ODG will remain a separate company.

In fact, it is already at work on a new set of technologies and products around head-mounted computing devices, with a new set of patents to go with them that Microsoft does not own. (And for the record it continues to have no outside investment, although as its Crunchbase profile points out that David Spector, formerly a VC at Sequoia who is now working on his own e-commerce startup called meCommerce, is an advisor.)

The government continues to be ODG’s primary customer, although as Osterhout reminds us, the pace of technology right now is such that the kinds of innovations being created for enterprises and other organizations has very direct applicability to the consumer market, too — and the reverse as well when you think about the wider trend of the consumerization of IT.

“In terms of what we’re doing [at ODG], we don’t make weapons. We make things that can help people do their jobs,” he says. “The real focus are features that are applicable in the consumer space, too.” In other words, ODG may already be talking to other companies for consumer products; or its door is open to that possibility.

We have contacted Microsoft multiple times about this story but have not had a response. We’ll add it in when we do.

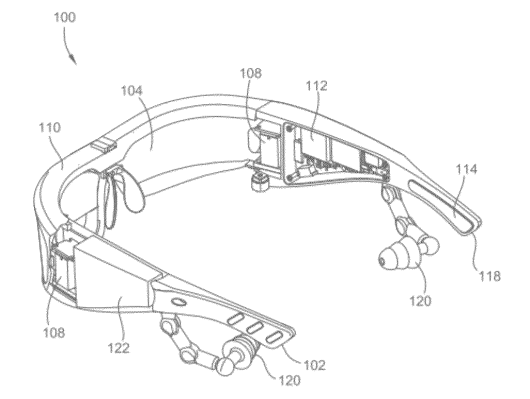

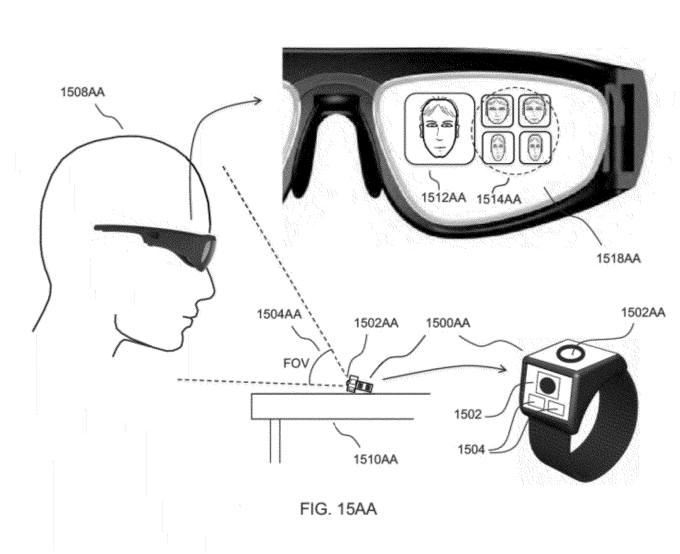

In any case, you can follow the patent trail for the basics. It’s a trove of over 81 patents, with six issued patents and “at least” 75 patents in progress both in the U.S. and internationally. You can trace them for yourself here; and here and here are links to two of the granted patents to illustrate the kinds of technologies we are talking about. They cover things like “See-through near-eye display glasses including a partially reflective, partially transmitting optical element” and “Video display modification based on sensor input for a see-through near-to-eye display.”

The deal between Microsoft and Osterhout actually closed last November, with the patents quietly transferring in January 2014.

It’s not clear what Microsoft intends to do with the patents but there are a couple of very clear directions it could take. The first is developing its own head-borne computing devices.

There has been a lot of speculation about what Microsoft might choose to do in this department. One clear area of opportunity for the company is in the area of its Xbox gaming and entertainment console. Developing a headset for that could work well with the company’s Kinect gesture-based features, but also potentially as a new screen for experiencing not just games but other media.

Interestingly one of the patents I noticed links the headset up with a separate device that looks like a wristwatch.

Pointedly, Zuckerberg was somewhat dismissive of how far Microsoft (and later, Sony) has gotten on this front.

“Microsoft hasn’t even gotten to the point where they have anything to demo yet,” he said. Later in his remarks, he implied that the kind of device that Microsoft is working on is too tied to a console and that the route to domination will be in head-gear products that may in effect act as the consoles and mobile devices themselves. “What we basically believe is that unlike the Microsoft or Sony pure console strategies, if you want to make this a real computing platform, you need to fuse both of those things together.”

There is also the area of enterprise services.

As we have pointed out before, Microsoft continues to focus on how it can hone and strengthen its relationships with business customers. While the Nokia deal will help it create more integrated software and hardware products to address the increasingly essential area of enterprise mobility, you can imagine that Microsoft is undoubtedly thinking of other enterprise hardware to extend that further.

The second direction Microsoft could take with Osterhout’s IP is doing what many large tech companies are these days: safeguarding their own technologies and current/future products while also making sure that they get a cut of royalties on other successful products if they feel they could infringe on IP.

This is not a route unfamiliar to Microsoft. Some have estimated the company could make as much as $2 billion annually from Android royalties. Just yesterday, Microsoft extended its Google royalty pool after it inked a patent deal with Dell covering not just Android but Chrome OS devices made by the latter company.

Notably, it looks like Oculus has just a single patent filed with the USPTO at the moment, for a “virtual reality headset.”

Osterhout — a career inventor who has created gadgets that range from shooting pens and early ID systems based on iris scans through to scuba and naval equipment — rarely talks to the press (thank you again for talking to me, Ralph). So I took the opportunity to ask him what he thought of the $2 billion deal between Facebook and the virtual reality headgear maker.

“I was amazed,” he said, elaborating with an explanation that sounded a lot like Zuckerberg’s criticism of Microsoft and Sony. “What surprised me most is the amount of money, given that it’s not a standalone, complete computing solution…it’s part of a solution that is designed to be plugged into something else.”

The other important point, he believes, is that the hardware that Oculus has shown is still far from being usable by the mass market beyond a group of hardcore gamers. “When you put weight on the head you put stress on neck muscles,” he says. “It might not be too comfortable for the duration.”

To be fair, this is a wider issue for the whole of the industry, he says, and has led to an “obsession” among device makers and inventors to work on solutions that optimise processing power and optics but keeping them as light as possible. “The last 10-20 years has seen a ton of patents in this area, but having something that is light weight and low power has been an unbelievable challenge.” He says what Oculus has done with its attention to low latency “is great.”

At the same time, such a big acquisition is great news for everyone working in the same area as Oculus. “An immersive experience [such as you can have with] head-borne wearables is a big deal,” he says.

While today is the age of the mobile device, longer term, echoing some of what Zuckerberg said about Facebook’s interest in Oculus, there will come a time when even those light, handheld devices will feel cumbersome.

“There is no question about where we will want our computing to go,” he continues. “If we can make it eloquent enough, head-borne computing devices will be transformative. It’s impossible for them not to be.”