Editor’s note: This is the first part of a two-part guest column by Zach Noorani that examines the ways in which equity crowdfunding might impact the startup world and the venture capital industry specifically. Zach is a former VC and current second-year MBA student at MIT Sloan. Follow him on Twitter @znoorani.

It’s fun to ponder the awesome disruptive power that equity crowdfunding might have over the venture capital industry. The very people who spend their days plotting the disruption of any industry touched by technology are themselves displaced by hordes of technology-enabled angel investors. How ironic.

VCs are even playing along. Take FirstMark Capital Managing Director Lawrence Lenihan’s response when asked if crowdfunding platforms threaten his business: “Why should I as a VC not view that my industry is going to be threatened?”

We’ve all heard ad nauseum about the JOBS Act, the proliferation of equity crowdfunding platforms (of which there are now over 200) and how they’re going to turn everyone and his grandmother into a startup investor. But could this realistically threaten the protected kingdom that is venture capital?

How Do You Threaten Investment Managers Anyway?

Simple, you take away their returns.

At a high level, the scenario for how crowdfunding could do this isn’t as crazy as you’d think. The crowd’s wealth is enormous in relation to the VC industry and has a miniscule allocation to the asset class. Increasing that allocation from miniscule to slightly less miniscule would represent a flood of new capital into the startup ecosystem that would bid up prices, over-capitalize good businesses, and fund more copycat competitors. As a result, everyone’s returns would suffer. [Insert generic comment about how VC returns are already bad enough and how hundreds more funds would face a reckoning if the industry experienced further systemic pressure on returns.]

1. How big is the angel capital market today?

The data is pretty sparse, but the Center for Venture Research (CVR) produces the most descriptive data available; it’s derived from a sampling of angel groups, so it mostly captures accredited angel investment activity in tech-related startups (as opposed to restaurants and such). For 2011, they estimate 320K people invested $23 billion in 66K startups. That implies each angel invested $70K and each startup raised $340K, both of which sound reasonable from an order of magnitude perspective. The handful of other attempts to size the angel market don’t materially contradict the CVR.

Additionally, unaccredited individuals invest as much as another $100 billion or so in “millions” of private companies run by friends and family. I’ll assume 10 percent (wild guess) of which reaches tech startups. Rounding up, that’s a grand total of $35 billion per year.

2. How much is $35 billion a year?

Collectively, U.S. households own $10 trillion in public equities outside of whatever’s in mutual and pension funds. We’ve got another $9 trillion in cash sitting at the bank. In total, we own $65 trillion in assets (net of consumer debt).

Assuming angel investors and friends and family invest ~$35 billion every year, then accounting for the three-and-a-half-year holding period of an angel investment means that approximately $120 billion is currently deployed as angel capital or 20 basis points (bps) of our total wealth. That’s not even considering how much of the $120 billion comes from outside the U.S.

3. How miniscule of an allocation is 20 bps?

Let’s compare it to the professionals. Despite continually reduced allocations to venture capital, many endowment and pension fund managers still target roughly 20X to 40X more exposure than the average U.S. household (Dartmouth targets 7.5 percent, Washington State is comparable). Obviously the comparison isn’t perfect as more than half of angel capital goes to seed-stage investments compared to only about 5 percent of VCs – not to mention that those VC dollars are professionally managed. But it’s instructive.

From another perspective, just 5 percent of the 6 million U.S. accredited investors* made an angel investment in 2011. (There are 3 million individuals in the US with investable assets greater than $1 million, and roughly 3.5 percent or 4.2 million households make more than $300K in annual income. Assuming 25 percent (wild guess) of the latter group meet the $1 million hurdle – therefore being double-counted – means there are 6.1 million accredited investors in the U.S.) Assuming the same ratio holds for the $10 billion per year from friends and family, suggests that another 1 million households (out of the 21 million that earn between $100K and $300K) invest $10K a year in startups.

4. What if crowdfunding doubled that allocation to 40 bps (10 percent of U.S. households with six-figure incomes)?

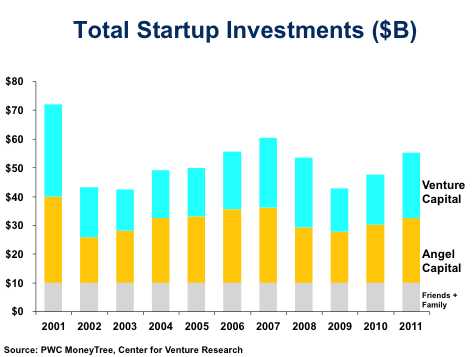

The chart below shows an estimate of venture, angel, and friends + family capital invested in startups over the last decade.

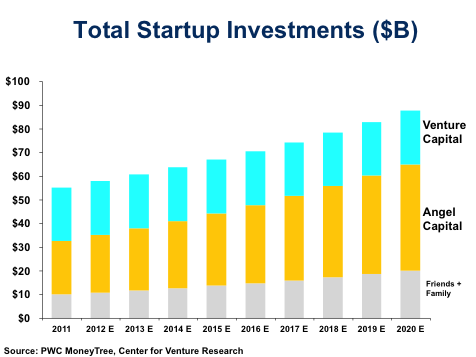

The next chart holds VC investment steady – though many would argue it will shrink in the coming years – and supposes that crowdfunding enables individuals to steadily pour into the market (8 percent growth rate) resulting in a doubling of angel and friends + family capital by 2020. No one, not the retail banks, brokerage houses, or mutual fund investors would even notice that incremental $35 billion was missing.

Two results pop out. First, that’s a huge increase – nearly 60 percent – in the dollars invested in startups. Second, the blue bar gets pretty tiny in proportion. By 2020, VCs would only be about a quarter of the capital invested in the sector (down from 41 percent in 2011).

Thus far, I have entirely ignored where all that new money might go in terms of stage, sector and quality of company. Just assume that for this much capital to enter the market, most would have to land in what looked like reasonable investments. In other words, the same places VCs invest. Valuations would get bid up, founders would be persuaded to overcapitalize, and derivative competitors would proliferate. All of which would make it harder for investors to make money: Armageddon for hundreds of VC funds.

So Where’s The Panic?

With about 5 percent of people participating currently, let’s call angel investing a hobby for the general population. For it to become substantially more than that – let’s say reach 10 percent as discussed earlier – people not only need to believe they can make an attractive return but also that it’s not that hard or laborious to do. But the truth is, it’s at best completely unknown whether most angel investors have ever made money, and if they did, it certainly wasn’t easy. This is why no venture capitalists are panicking.

The debate over angel investing economics goes around in circles. Conventional wisdom says that angels are the dumb money. More delicately phrased: VCs have “consciously outsourced consumer Internet companies’ bad market risk onto the angels,” says Benchmark Capital co-founder Andy Rachleff and as a result “typical return for angels must be atrocious.” Robert Wiltbank, John Frankel, and David Teten counter that the data demonstrate quite the opposite.

The data in question is from from Robert Wiltbank’s 2007 study:

- 13 percent of the membership in 86 angel groups – 539 angels in all – submitted data on 3,097 investments made between 1990 and 2007.

- 1,137 of the deals had reached exit and only 434 of those had enough information provided to be analyzable.

- The big result: ~0.08 percent of angel investments made from 1990-2007 (assuming 30K/year) generated a 30 percent+ IRR.

Ignoring the huge potential for sample bias and inaccuracy, a generous conclusion would be that somewhere between some and many investors from organized angel groups achieved attractive returns over a period that included the entire Internet bubble and excluded the financial crisis.

That’s great for those 539 investors, but it doesn’t do much to refute the conventional wisdom, particularly for the casual end of the angel market, which crowdfunding would most resemble. In the face of such uncertainty, non-hobby investors will require actual evidence that the early-adopting crowdfunders are making money before reallocating their portfolios in any real way. Shall we adjourn for about five years to let the proof accumulate?

There is, however, one interesting observation from Wiltbank’s study: angel investors spent 20 hours on average conducting due diligence on each investment and 40 hours on investments that had a top quartile exit. That’s in addition to due diligence on investments that they passed on and deal sourcing, which, combined, arguably should comprise most of their time. That doesn’t sound easy at all.

Check back next week for Part II where I explain why, despite everything I just told you, it would be premature to count out the crowd just yet.

[Image: spirit of america / Shutterstock.com]