Everyone is now familiar with, and with a few significant exceptions, has moved on from, the blood-freezing image of the man on the subway tracks about to be struck and killed. The circumstances of the photo and the actions of the photographer are not the topic of this article, partly because such discussions are incomplete, but mostly because I’m interested in the way the photo has propagated, and how we may expect similarly powerful but controversial images to propagate.

When our media is filtered and refiltered, bleached by content guidelines and automatic takedown algorithms, we run the risk of living a life with the objectionable and graphic and terrifying, in other words the real, strained out. That makes it the more striking when something like the man on the tracks appears — although this time, puzzlingly at yet perhaps appropriately enough, it came printed on dead trees.

I wrote in Surveillant Society that putting an Internet-connected camera in the pocket of every person was one of the most important developments in recent history. And although the man on the tracks isn’t the best example of this (the photo was taken on a DSLR by a photographer on his way to an assignment), it serves well enough; The pervasion of cameras means the documentation of everything, and this is at odds with the prim, “curated” platforms on which that documentation is most often shared.

So while a picture of a meme-themed cupcake has no problem making its way onto the credentialed, aboveboard network of promotion and instant visibility, other things, perhaps more important things, may find it difficult. A soldier posting an image of a wounded comrade, for instance, or images taken live at a suicide bombing site, might have more of a problem.

I’m not just talking about simply a place where graphic images can be put. And this isn’t an argument against the idea of removing content many people would find disturbing. That’s a whole other discussion — and one worth having, but not here.

The simple fact is that we have two huge forces that are about to collide, not head on, but at least glancingly. You have the mass deployment of the tools of instantaneous documentation, and content networks that rely at least partially on centralized curation.

That is to say, images and content that are culturally or otherwise important may be incompatible with the scope or ideology of the services through which they must pass. It’s a conflict of interest that we should keep in mind.

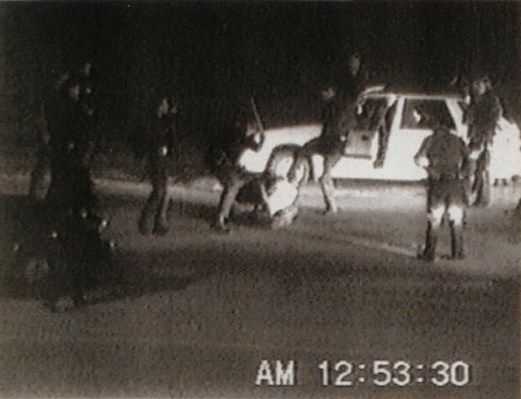

Because it’s the same conflict of interest that prevents people in Iran and China from reading certain Western or secular websites. It’s the conflict of interest that might prevent a video like that showing Rodney King being beaten, or an image of a protestation by self-immolation. Who holds the means of communication is not a simple question, or an idle one.

Your law or mine?

Fortunately, it’s also not a critical question right now. Information that’s truly important acquires a special kind of virality and propagates however it can. A world-changing image like those we’re all familiar with, or the news of a dictator’s death, or what have you, always makes its way out eventually.

Terrible things make their way out as well. The man on the tracks may be a chilling, almost sublime image, but it’s arguable that it should never have been published at all. And to that end, there will always be a way for such things to be posted, for enjoyment in poor taste by gawkers and fools.

The specter of censorship always looms vaguely over the Internet but rarely touches down. And hopefully, that trend will continue. But the “open” Internet is still a myth, speaking in terms of ideals, and while it doesn’t make sense to tell Facebook it should stop censoring (it’s part of making a safe and successful online community), it does make sense to note that the biggest websites and services in the world are, in fact, actively monitoring content.

That’s not a problem as long as you agree with Facebook, Google, Twitter, the government, your ISP, and so on over what stays up and what gets taken down. But that’s one hell of a shifting foundation on which to build a platform for free speech.