Udacity, a startup focused on bringing free university-level educational worldwide, is today announcing a significant new investment: $15 million in Series B funding in a round led by top VC firm Andreessen Horowitz. Also participating in the round were Udacity’s previous investors, Charles River Ventures and Steve Blank.

To date, the company has raised $21.1 million in outside funding for its platform which offers online courses in Computer Science, Mathematics, General Sciences, Programming and Entrepreneurship to students who may not have the time, money, access, or inclination to study in a traditional university setting.

As a part of the funding, Andreessen Horowitz general partner Peter Levine is joining Udacity’s board. Levine has also penned his thoughts on why the firm chose to invest in Udacity, and it’s an article worth reading in its entirety. But to sum it up, the firm believes in this concept of “software eating the world,” which means that more and more businesses and industries are being run on software – from agriculture to education, and the firm is backing those it thinks has the most potential to disrupt the established ways of doing things. In Udacity’s case, they’re disrupting the idea that access to higher education is something which can only be found through the traditional university system. Says Levine of startup, it’s “a team and company that we’re absolutely convinced will change the world.”

Although there are now numerous startups attempting to disrupt higher learning – Khan Academy, 2tor, ShowMe, Udemy, Grockit, Coursera, Lynda and StraighterLine come to mind – the investment from Andreessen Horowitz now makes Udacity one to watch in terms of becoming a profitable business. Although classes at Udacity are free, students can optionally take certified exams which have some cost to them, and the startup is beginning to place graduates in full-time positions, which helps Udacity earn referral fees.

Udacity plans on using the new funding to continue to build its technology platform, which will include mobile applications and the introduction of adaptive learning techniques which will change based on students’ capabilities. They will also scale up in terms of classes offered and work more with those in related industries on graduate referrals.

Udacity’s Beginnings

Co-founder Sebastian Thrun, who started the company with fellow roboticists David Stavens and Mike Sokolsky, is also well known as the co-inventor of Google’s self-driving car. He’s someone who goes after the bigger and tougher problems of our times – a mindset shared by his Google colleagues. “Working with people at Google – most notably [Google founders] Sergey and Larry – I’ve learned that you can spend your time tackling small problems or big problems, and you end up spending the same amount of time for either one,” Thrun explains, “so you might as well spend your time solving big problems.”

Prior to founding Udacity, Thrun was also a Stanford professor teaching classes on artificial intelligence. After seeing the impact that Sal Khan’s Khan Academy was having on education – Khan’s classes reach hundreds of millions of students around the world – Thrun was motivated to do the same with his class. “The initial way we announced it was really chaotic – we just sent out an email that said you can take our class for free online,” he says, speaking of the spark which eventually became the online educational platform that’s today’s Udacity. That first night, 5,000 students signed up. When the class reached 160,000 students, Stanford asked them to shut down enrollment. “They couldn’t fathom what was happening,” Thrun said. He decided to leave the university and launch Udacity.

How Udacity Works

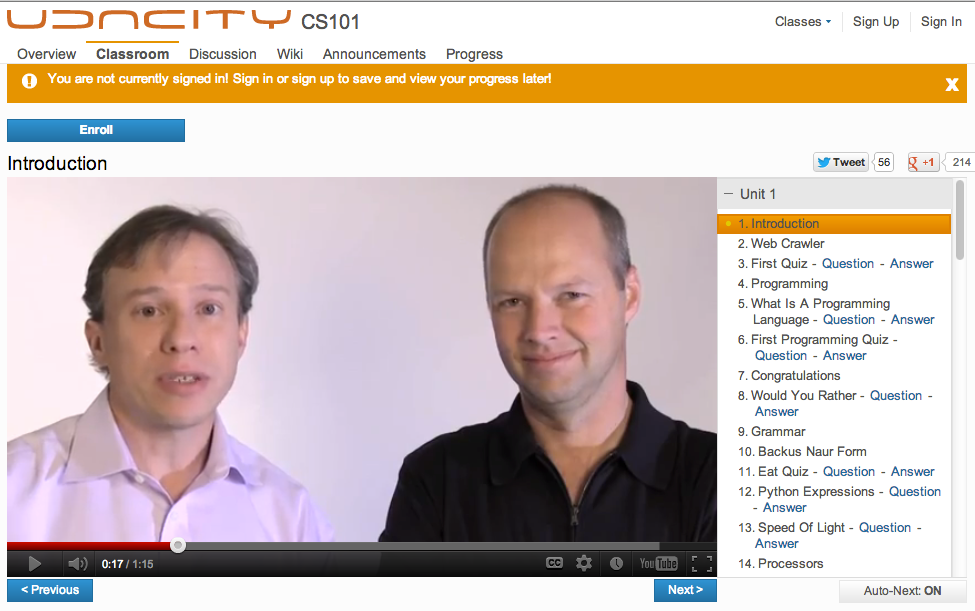

Udacity, unlike some other attempts at democratizing higher ed, does not just offer webcam recordings of lectures. Instead, Thrun describes Udacity’s classes as being almost like a game. “Students are bombarded with questions and puzzles and quizzes, rather than lectures,” he says. “We shunned the lecture entirely.” In Udacity’s classes, students are actively problem-solving, after a professor introduces the topic briefly. “We believe that learning by doing is more important than learning by listening,” Thrun explains. This model, similar to that of the “flipped classroom,” is what some are betting on as the future of education. It’s essentially an argument that “book learning” is an outmoded and ineffective way to impart true knowledge.

Udacity’s platform is more than videos. It has its own learning management system, a built-in programming interface for solving coding challenges, and a discussion forum and social element modeled after Facebook. Today, it offers 15 classes, but with the new funding, that number will grow. In addition, several technology firms recently announced plans to provide course material, instructors and funding, including Google, Microsoft, Autodesk, Nvidia, Cadence and Wolfram Alpha. These classes will start in January.

The startup now has over 753,000 students signed up to take courses, and the company is beginning to work with others in the industry to help place those students in jobs. To date, 20 Udacity graduates have found employment this way.

Challenges Ahead: Sometimes, A Physical Classroom Is Still Needed

However, when expanding outside of the Silicon Valley tech industry, as Udacity plans to do with courses that could range from biotechnology to pharmaceutical training, for example, a question is raised: can virtual learning ever fully replace the in-person learning environment, especially when students need to do work in a lab setting? To this end, Udacity is already experimenting with partially physical and partially virtual classes, says Thrun. But so far, the topic at hand has been entrepreneurship – something that doesn’t necessitate access to things like chemicals or microscopes or equipment. That being said, if employers themselves are starting to get involved with the training of potential hires through Udacity, it’s likely that they may consider going the extra mile to host students on-site in the future.

That leaves the other big “if” – will the world’s employers really value a Udacity “degree” the way they value a traditional university degree? “It remains to be seen,” says Thrun. “I think that’s going to be a phase shift that’s going to take some time.” But with the new funding, Udacity has more time to make that shift happen.