Facebook has to show more ads to make more money, right? Wrong. Or at least not necessarily. If it expands its new off-site ad network and Gifts e-commerce product, it could rely on its data, not its traffic, to grow its revenues. That would leave its site and apps uncluttered, designed to maximize enjoyment, the amount we share, and our feeling of connection instead of page views.

You might say I’m a dreamer…

Until a month ago, the world thought Facebook was stuck between a sinking rock and a hard-to-monetize place. The fact is that the user base is shifting from the desktop where Facebook can show up to ten ads per page and take a 30 percent of games payments, to the tiny mobile screen.

This has been terrifying to investors and a bad omen for the user experience. Many assumed the only solution was for Facebook to show a lot of ads on mobile. Wall Street wasn’t even convinced users would click them or advertisers would buy them. It turns out Facebook’s mobile ad click through rates are impressive and advertisers are lining up for them, but the social network would still need to drown out organic news feed content from our friends with ads.

But Facebook moves fast. It had been testing off-site web display ads, the first step to an ad network, on Zynga.com. Then a few weeks ago it revealed it would begin letting advertisers pay it to use its wealth of biographical and social data on us to better target ads shown on non-Facebook mobile sites and apps — essentially a Facebook mobile ad network.

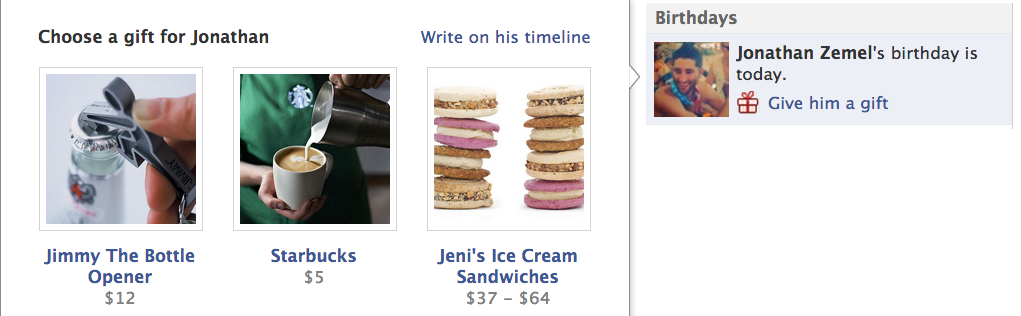

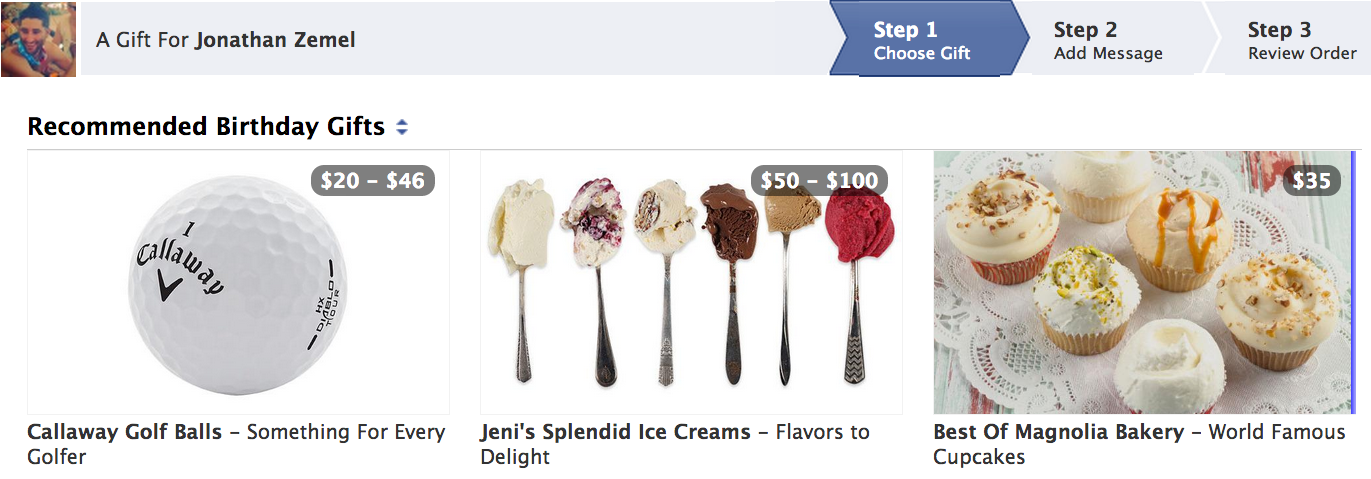

And then on Thursday Facebook launched Gifts, its entry into the e-commerce market that suggests and lets users buy real gifts and digital gift cards for friends. It earns a percentage of each sale.

Fewer Ads, More Revenue

With these two products, Facebook has paved a second path to financial success.

The original path: monetizing the incredible amount of time users spend within its site and apps.

The new, second path: Monetizing the incredible amount of data it has to target ads to users when they spend time elsewhere, and to recommend them relevant things to buy.

Both branches of the second path will help Facebook avoid a fundamental pitfall. The compromise ad-supported services face is: “How can we accomplish our mission and offer the best service possible while distracting from and interrupting that service with as many ads as people will tolerate?”

Since its launch, Facebook has commendably skewed the balance in favor of the user experience, minimizing the presence of ads and focusing on making them as relevant as possible. But going public has brought pressure to earn more money. Readjusting the balance in favor of revenue threatened to make Facebook worse.

But the second path is subtler, and aligns money-making with making the world more open and connected. All it requires is that you share and that you feel close to your friends.

A lot of online ads are irrelevant interruptions. But Facebook’s ad network lets it use your gender, age, location, work history, interests, friends, and app activity to help other sites and apps show you ads for things you want. That means it earns more ad money without showing any more ads.

Gifts analyzes the profile of the person you select to buy a gift for, and recommends products that other people gave to users with similar characteristics. The more Facebook knows about you, the better the recommendations it can give your friends on what to buy you. And the better Facebook knows who your best friends are and when their important moments like birthdays are, the more accurately it will be able to suggest who you should buy for.

I’m not saying ads on Facebook are going to disappear soon, or even ever, but that’s the direction it could be heading. There are big benefits to showing fewer ads or at least not showing more. Namely, an ad-free Facebook experience would be less annoying and would encourage more browsing and sharing.

There is one catch. For most people, Facebook quietly using their data to improve offsite ads and onsite e-commerce wouldn’t be too big of a deal. Or they wouldn’t even really understand what was happening. However, a vocal minority might loudly disapprove of their Facebook data being employed to target them with ads that are so relevant they might seem creepy. But Facebook has always had to deal with these people, and it hasn’t caused much of a problem so far.

So when you think of Facebook now, remember the balance between the user experience and the volume of ads it shows isn’t a zero-sum game. In fact, if Facebook plays its data right, the number of ads it shows could approach zero some day.

“And the worrrrrld will be as one.” Sorry, John.