A recent post by a defecting Googler (at his new and previous home, Microsoft) suggests that a fundamental reordering of Google’s priorities has made it far less than the company it once was. A sudden comprehension of the danger posed by Facebook’s ever-expanding platform caused the company to enter a sort of berserker state, focusing solely on reinventing social while neglecting or amputating anything that didn’t fit into its new mission. Or so the tale goes.

There have been times recently when I’ve felt the need to deflect a few of the slings and arrows trained on Google. This time, however, they are well-deserved. Google’s big bet was based on bad instincts, jealousy, and hubris — not the curiosity, experimentation, and agility that have characterized them theretofore.

Could Google+ ever have been anything but a failure?

Just as a caveat: the problem with criticizing Google+ is that it’s a good product. It’s not for everybody, and there are problems with how it models social networks, but the only real problem it has is that there’s no one engaging with it. There are, of course, some people on it, but it’s hardly at a level that would make it what Google obviously intended it to be.

That said, Google should never have thought of it that way in the first place. The concept, as well-represented as it is in the product, was wrong to begin with. The whole project is a failure to understand their strengths and their competitors’ weaknesses.

Looking for clues in how Google’s products have improved or differentiated themselves previously (whether they flew or crashed) isn’t much help. You can’t dissect Google+ by proxy in Wave or Gmail. It’s better to look at their intentions.

It seems that Sun Tzu has much to offer Google respecting their approach to social. Nietzsche, too.

“Those skilled in war bring the enemy to the field of battle and are not brought there by him.”

“Sharing is broken.” There’s a hell of a place to start. To make such a statement about a sector with so much diversity and velocity is a red flag to begin with. First, because it isn’t broken, it’s a work in progress. And second, even if it were broken, Google has never fixed anything before.

Google never said “What you’re doing is broken. Use our thing instead.” They always said “Did you know you we can do that too, for free?” Did they say Excel was broken when they let you make spreadsheets in Docs? Did they break down email to its bare bones and remake it for Gmail? Of course not. Google was about ubiquity, diversity, and a few memorable little quirks or improvements that set them out from the crowd.

To attempt to build something new, a la Apple, with the assurance that company likes to make (“This is the best way, which is why we made it the only way”) is not a Google strength. They just aren’t good at making new things. Never have been. Making existing things easier, faster, more accessible — sure. But inventing them? Not so much. So the idea that they were going to invent a new way to share should have rung alarm bells to begin with.

Sharing was never broken; Google merely found that they were losing a battle they had not even prepared for. Their declaration of war was a declaration of defeat.

“When torrential water tosses boulders, it is because of momentum. When the strike of a hawk breaks the body of its prey, it is because of timing.”

Google is neither small nor weak. It is immense, established, technically proficient, and, to an extent, trusted. Within the confines of non-monopolistic actions, it holds search like a gun. By rewarding those sites and services that agreed with its planned trajectory for search, they cast a shadow on the others, too light to be called punishment but still keenly felt. They are a household word, so closely identified with their service that they have become a global euphemism for searching on the internet.

They are a company of momentum — some would say inertia, but inertia in tech is soon eroded by more energetic competitors. No, Google has momentum, and their force has grown large enough that, like two gunmen in the old west, the town wasn’t big enough for them and Facebook. The conflict was inevitable. Which is why it’s so strange that instead of choosing to be the mighty river, they opted to strike as the hawk.

What was Google+? A single product, made to compete with an entire ecosystem. A product, moreover, lacking the single most important ingredient: users. Now, unless you are sure that your product is far, far better than what’s out there, you are not the hawk. Steve Jobs knew he was the hawk in 2007, and he knew that what he was doing would break its prey. The look on his face while he describes the competition is one of sheer predatory glee.

Is Google+ the iPhone to Facebook’s Palm Pilot? Surely not. Who judged that it was? That person is incompetent.

“The great fighters of old first put themselves beyond the possibility of defeat, and then waited for an opportunity of defeating the enemy.”

Google was, against all reason, impatient to get into social. There’s nothing wrong with wanting to build a social network, of course. There are many kinds and many approaches, from niche to meta, from creative to filtrative. The Internet is a community of communities, and it is natural, even admirable, to want to create a new one. But Google decided that instead of creating a new one, a new space for itself, it would instead attempt to unseat the largest and most stable of them all. Hubris!

Facebook, of course, is not unassailable. It too will pass away. It is after all only the latest in a series of improvements on the general social network model. It has proven to be more flexible and resilient than its predecessors, but it isn’t immortal; even now there is a hum of discontent among users, low in frequency but just audible. Trust is an issue; ads are an issue; filtering is an issue. Will these issues destroy Facebook in the next year? Of course not. But as another saying goes, if you wait long enough by the river, you will see the bodies of your enemies float by.

Who can wait longer by the river? Facebook, a transitory model for connecting people that may or may not reflect the zeitgeist of social communication in five years? Or Google, which indexes and tracks the entire visible internet and whatever it can digitize from the analog world? I feel sure that, barring disaster, it would be Google on the shore watching Facebook go down the river.

Google always played a long game, but failed to in social. Why didn’t they bide their time, refining their ideas, pretending total disinterest? Making Facebook seem like the only game in town has many benefits. People distrust monopolies. If people feel they are choosing to be on Facebook, they will justify that choice. If the choice is made for them, they will find a reason to resent it. Google must know this, because they experience it every day.

So why did they jump the gun? The data! That beautiful, plentiful, personal data! Google is a datavore; its reason to exist is to organize all the world’s data, using ads to fund its habit. And on the table before them, a feast unprecedented in depth and variety! Imagine the amount of data produced by a single day of Facebook’s operations. But, like Tantalus, Google is prohibited from reaching and and taking it even though it’s right… there.

Why did Google launch a social network? The same reason a child snatches a cookie from the cookie jar. They simply couldn’t resist.

“To win one hundred victories in one hundred battles is not the epitome of skill. To subdue the enemy without fighting is the epitome of skill.”

Could Google ever have won? I think so. But not by blitz. By envelopment.

Google’s presence is felt all over the net. Remember that browser plug-in that sounded a siren whenever it detected Google in any way, shape, or form? People tolerate having Google everywhere because, for the most part, it’s a neutral presence, like streetlamps in a city. You’re logged into Google like you’re a resident of the city. You don’t think about it, and you don’t have to think about it.

The opportunity this gives Google is simply to be where you are, and have you know it and not mind. That’s huge. Facebook gets flak for being where you are, because Facebook is a place you go to, not a presence that surrounds you. Facebook is a personal place, something you log into, and you don’t want to have it following you around. On the other hand, you expect to turn around and find Google there, the way you expect your own shadow.

The natural thing to do given this advantage is, in fact, what Google did. They just did it too hard. They made a whole competing service, completely empty and more or less disconnected from everything, and threw it at the enemy.

It seems to me that they only needed one part of it: the +1 button.

Google’s ubiquity would let that button exist almost everywhere a user goes. No plug-in needed, no sign-up or tracking by the site. The URL or the resource itself (video, music, image) is already known to Google — you probably found it through Google anyway. All that’s missing is a button or key or extension that +1s it. The rest follows naturally. (Obviously this is part of what the extant +1 button does, but we are building it again from scratch.)

What happens when you +1 something in this simple system? Well, on Google’s side, it gets added to a pile of data: timestamped and correlated to your other activity and the activity around that site and similar sites, it would be a valuable unit of deliberate user input. And of course it makes one big number go up by one, whether the site or resource wants to show it or not — just like its PageRank stat or hit counter. A number we can all agree to use because it’s not for some community, some network, some service. It’s just for the Internet. Google already tracks visitors and sites and traffic, now they’ve just added one more thing to the pile. It’s a neutral party and it’s already present wherever you go.

And what about on the user side? Well, it could easily be tied to other actions, since once you +1 the thing, Google doesn’t really care what happens next. You could forget you ever did it. Or you could tie it to actions like posting or liking it on Facebook, or sending it to your Tumblr, or tweeting it. Whatever you want. It’s just a trigger you pull on a website — what happens after you pull the trigger doesn’t matter to Google, all they care about is that the trigger was pulled in the first place.

Oh, and don’t forget that everything you’ve +1’d will be saved to your Google profile – you can go and check it any time you want, by date, by site, whatever. Why, it could even have a little snippet or image for each one, or you could add a tag or caption; you could even do that right when you +1 it. And maybe if you +1 a video or piece of music, it’ll have that embedded for you just for your convenience. Like the other Google services, you’ll have a few templates and layouts you can use to make this little pile of data your own, like Gmail. Naturally it’ll be searchable. And if you just want to upload something, that’s cool too, it goes into cloud storage and is part of your collection like everything else.

Now, this information is of course private by default, and although you contribute to total metrics, your individual +1s are anonymous outside of your account. But a few people will want to make them public. And why shouldn’t they? People like to share things, and this +1 thing is straightforward, user-friendly, and versatile. So they make it public. Now people can see what they’ve +1’d.

Once a few are public, why, of course people will want to see what other people are doing. And you don’t want to have to go to their profile all the time. So Google will let you add them as a connection, probably with rules like they can’t see things with certain tags, or what have you. How do you add them? You go to their profile and +1 it, of course. Now when they +1 things, it’ll show up in your stream, and they can tweet or post it on Facebook later if they want. And did you know, Google reminds you, that you can click on their little icon any time and instantly connect via chat, audio, or video, no plugin necessary? You can even drag a friend’s icon in to invite them. But hey, it’s not a “social network” — these are just things you can do using Google services. You can do all of them or none of them.

All this happens outside of Facebook and completely parallel. It takes place naturally, people can use it as much or as little as they like, and it’s only a destination if you make it one. It doesn’t replace Facebook, it augments it (and other services) with a more generalized mechanism for saving and recommending things on the web.

If Google had done this, if they had built a community around a mechanism instead of trying to meet Facebook head-on in battle, they might have succeeded. They might have built an Internet-wide community of individuals who want to track, save, and share what they do on the web. They’d also have a simple way of letting users connect to one another in a natural and very Internet way. And they’d have done it all without antagonizing anyone openly; it could plug right into other services, if they play nice, and Google looks like the user-focused facilitator it once was.

And coincidentally, all of a sudden there are a hundred million people using that +1 button, reading friends’ updates, chatting and sharing seamlessly, and starting to question what it is that Facebook has that Google doesn’t.

“Battle not with monsters, lest ye become a monster.”

(This was originally the title of this post, but I decided to have a world-class pun instead.)

But Google didn’t do all that. Google+ was born and not molded, naked and altricial and all at once instead of incrementally and subtly and responsively, into a world that hadn’t asked for it, and didn’t really need it. What are the wages of Google’s tactless warfare?

Sun Tzu actually does say “To defeat your enemy, you must become your enemy.” But he meant it in terms of understanding. Google has actually become their own enemy, both in how they have thwarted their own development and how they have donned the tainted garb of monopoly. These clothes were made for Facebook to wear in social, but Google has convinced the world that they too are a good fit.

I’ll be less obtuse. What Google has done, remarkably, is to transfer all the worst qualities of Facebook to themselves while managing to retain almost none of the good ones. They were behind the scenes; now they are in people’s faces. They were a service; now they are a destination. They monitored the web; now they distort it. Whether or not these things are really true, they are now popular perceptions of Google. Facebook meanwhile has taken on a few of Google’s best characteristics as it has expanded across the web.

Google lost its status as a neutral party because of a number of choices that minimized the user and promoted themselves unilaterally. How many of these decisions were made deliberately, and how many innocently? It’s hard to say, but in the end the analysis is merely academic. The reality is that they are no longer trusted. The liberties they took with their best assets were questionable at best and infuriating at worst. And they have had the side effect of drawing attention to just how much power Google wields.

Two years ago, Google was a utility. Now it’s a monopoly being watched not only by the government but by every user, many of whom have been burned or frustrated by one of the many changes. Two years ago it was Facebook in that position, and people were excited about the prospect of a better, more independent social network. Now people are uploading videos to Facebook instead of YouTube. Think about that.

And worst of all, they can’t go back. They put too much wood behind the arrow. Maybe it’s more apt to say that instead of making a new arrow, they used the wood to make a new bow — and now all their old arrows, the ones that built them a globe-spanning empire, had to be refitted.

The changes are too big, the culture too different. They can’t try again; they can’t put it down the memory hole like they have with other, less monumental products. How can you call a do-over on two years of fundamental reordering of the entire company?

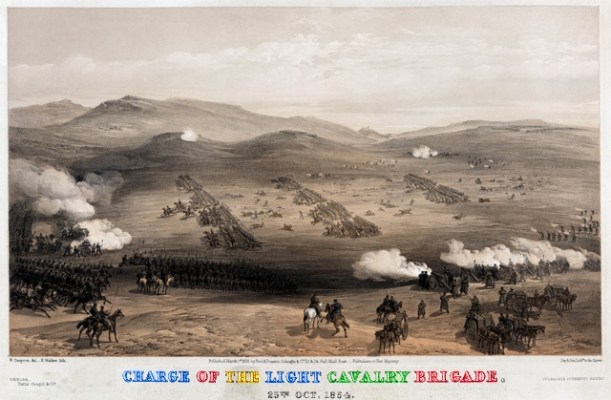

Is this Google’s swan song? Of course not. But it is almost certainly their biggest failure by a good distance. And it’s not a Flubber-like experimental miss like Orkut and Wave and the many Labs projects snuffed before their time. It corrupted Google’s primary mission, angered users, and eroded trust. Maybe the worst of it is that Google+ could have been so good. It could have been so Google. But a series of poor choices, misjudgments, and plain stubbornness resulted in the poor thing being sent alone and friendless into bloody battle with an entrenched and veteran opponent.

As the French General Bosquet remarked upon witnessing the charge of Cardigan’s light brigade: “C’est magnifique, mais ce n’est pas la guerre: c’est de la folie.”