The “Scene,” a loosely-knit network of hackers extant in some form or another since the days of diskette-based media, is in many ways the precursor to Anonymous. Unlike that slightly schizophrenic collective, the Scene’s marching orders have always been clear: distribute movies, TV, music, and games within itself — and if they leak to the general public, well, what they do with it is their business.

This rich subculture deserves a post of its own (their ASCII art and NFO banter alone, in fact), but today they are in the middle of making yet another change to the way they strip content of its unnecessary components. First it was NoCD, then it was cracked-DRM, and perhaps now, no-ads.

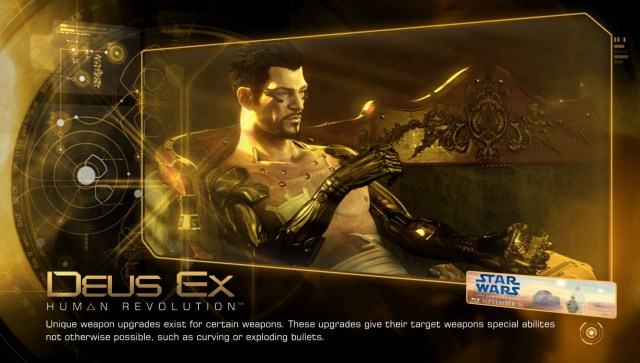

In-game advertising is kind of a third rail right now in gaming. With many publishers and dev houses under fire for things like day-one DRM, “premium” content that should have been included to begin with, and platform-exclusive items and maps, further exploitation of gaming content might push more gamers towards the dark side. Case in point: a recent update to the long-awaited and well-reviewed Deus Ex: Human Revolution that adds advertisements for the new Star Wars Blu-rays to loading screens, sending users into a frenzy.

Their frustration isn’t hard to understand. They paid for this game. Why are they being advertised to? Why wasn’t this mentioned before? Why activate it now?? Why Star Wars? Will Jersey Shore be next?

While the Scene is ostensibly a private community, it has grown to be a reliable “service” that breaks the fetters publishers add to their content. Originally it was simply about freeing games and programs from their disk-based distribution method, a side-effect of which was the necessity of modifying how the program was installed and run. Later, as games began to check whether the “play” CD or DVD was in the drive, though that disc held no content necessary to run the game, Scene hackers started snipping out the portions of EXEs that looked for the disc. Still later, as more complicated forms of verifying the legitimacy of games and apps developed, an arms race developed. Circumvention methods for StarForce, SecuROM, and always-on DRM have grown increasingly complicated, and the modifications to the games themselves have become extremely sophisticated.

But the goal has always been the same: free the content. Whether it’s for the Navy tech who wants to play Assassin’s Creed 2 while off duty on the carrier, or for the lazy/unscrupulous basement-dwelling game pirate, the principle is the same. Information wants to be free, be it text, graphic, video, or interactive.

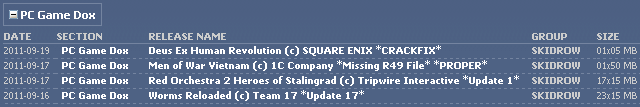

In-game ads present a different problem. They don’t limit the functionality of the game; in fact, they are frequently closely integrated with it. Sponsorships, real cars, everyday products, these things often make a game better and more realistic. So no one has really cared to go in and excise the code that puts a Subway ad on the virtual street. Ad-supported gaming on Android is blowing up. Targeted ads on browser-based gaming networks boast huge viewer minutes per display. Yet this addition by Eidos, or whoever made the decision, has been harshly criticized, and a number of cracks and fixes have shown up on the net that address the ad issue.

Why was this time worse than, say, Need For Speed: ProStreet, which rubbed sponsorships in your face and had raceways fairly wallpapered with ads? Because not only are these ads totally unrelated to or integrated with gameplay, but they were added after the fact and without any warning. It’s a breach of trust.

So the “fixes” began to appear. I wouldn’t download any right now, as none of the reputable groups have made a patch, but Reddit user go1dfish has put together a simple guide for Windows that should work. The outpouring of frustration and resultant support from the hacking community suggests a dire future for in-game ads. DRM has grown to be a punishment for legitimate users, and in-game ads will soon be the same way — not because either one is fundamentally a bad thing (even Blizzard’s always-on DRM in Diablo III has some good reasoning behind it), but because companies are going to refuse to implement them reasonably.

There will likely be a bit of an internal war in the Scene over whether a no-ads version of the game is “proper,” as technically the ads may be part of the game. But I remember the in-Scene conflict over CloneDVD groups, which more or less worked itself out as the situation evolved. In the end, ads will be a burden to the user (because publishers have no common sense), and people with the skill to remove them will develop the desire to as well.

DoubleFusion, the firm responsible for the DE:HR ads, says that according to its research,

Three-quarters of gamers surveyed said they feel better about a product advertised in a game and 70% said they feel in-game ads give the company a cutting edge image. Four out of five say they feel games are just as enjoyable with ads.

I’m sure many of us would find something to disagree with there. But my impression is that there simply isn’t enough data right now. In-game ads aren’t nearly as prevalent as banners, text ads, flash ads, interstitials, 30-second spots on Hulu or broadcast, or on-screen placement. It seems unwise to draw conclusions so early in the game, but I would submit that gamers as a demographic are far more technically savvy than the average, and I’m pretty sure that correlates with rejection of online advertisements. In-game ads not being rejected yet speaks more to the scarcity and relative mundaneness of attempts so far. When Chun Li starts chugging Red Bull between rounds and attributing the power of her tatsumakisenpukyaku (I write from memory) to that drink’s refreshing taste and unique blend of… well, you get the idea. Gamers aren’t going to buy it, so to speak.

The decreasing relevance of moddable platforms, however, suggests that this imminent advertising revolt may be a small one. After all, you can’t patch iPhone games, or at least no one but a microscopic set of users are going to. So unfortunately, the process of consumers wising up to tricks like in-game ads is counteracted by the process of them being less and less in control of the platform on which they are advertised to.

They’ll make a ruckus, but like so many boycotts, complaints, and petitions before, they’ll end up buying the game for their favorite console anyway and cursing the publisher for a few seconds the first few times they see an ad. After that, like on every other platform, they’ll cease to perceive the ads as an intrusion, but simply as an unwanted but natural extension of the medium.

So unfortunately, the Scene’s battle against in-game ads won’t result in a groundswell of casual gamers cutting the advertisements out of their games. And the fact is that they are more of a vestigial component of the games distribution system now. Game-as-service is the new word, and things like Valve’s free-to-play TF2 and Call of Duty’s $50 yearly Elite service are likely more representative of the future of gaming. Fairlight, Skidrow, Razor 1911, Myth, Class, and all the rest of the groups are proud holdovers from a simpler time, a marginalized Illuminati of piracy.