Adding usernames to a messaging app may seem like a standard feature, but for Signal, such identifiers were anathema to its mission of total privacy and security — until now. The upcoming 7.0 version adds usernames, but the company’s president, Meredith Whittaker, explained that this was nowhere near as simple a decision as it may sound.

The new feature sounds simple: You register a username and that appears instead of your phone number. But why do this at all when everyone already has contact names, and Signal is totally private anyway?

In an interview onstage at StrictlyVC LA, Whittaker explained the lead-up and complications that attended what they believe is a crucial new protection.

“Let me start by kind of explaining that with an example. In India recently, it has become a requirement, in order to obtain a SIM card, to submit to a biometric facial recognition scan. That is not just happening in India, we’re seeing a number of jurisdictions where to obtain a phone number, you are required to provide more and more personal information. Some, in some places like Taiwan, that is linked to government ID databases that often get breached and cause a lot of problems,” she said.

This isn’t so much a problem in the U.S., where there are burners and SIMs aplenty, though private data is also available on private markets. But around the world, this trend is accelerating, she said:

“A request we got frequently from journalists in conflict zones, and from human rights workers, was like: Hey, we love it, but the phone number is a real issue for us. We need to be able to speak with people without sharing this information. We need to be in groups of strangers where we’re not afraid that they can scrape that. And we need to be able to initiate conversations with others without sharing our phone number, because again, that, that’s my biometrics, that’s everything else, and that can leak a significant amount of information.”

Essentially, Signal’s dogged reliance on a durable and increasingly non-private identifier, phone numbers, was shifting from a legitimate product choice to a serious threat to a significant number of users. They decided they needed to add an optional obfuscation layer without adversely affecting usability or security.

“So we basically turned our architecture inside-out to support this, and to support it in a way that I’m really proud of,” Whittaker said.

The clutch move was to implement usernames without saddling Signal with new, large-scale moderation obligations.

“As Signal we do not want to take responsibility for content — we are not entering into the content adjudication business. But of course, with usernames, traditionally, you create a new namespace, right? You create something that you, in effect, have to monitor, perhaps police, perhaps censor.”

Image Credits: Signal

It’s a problem that far larger organizations have trouble addressing, as millions or billions of users register and change names that could in themselves be rules violations — a name is just a short string, and can as easily be “RainbowBubbles” as it can be “Kill_all_[insert slur here].” Impersonation, scams, all kinds of issues are equally possible in username fields as they are in posts or profile fields.

Signal’s solution to this is, basically, to eliminate the ways these methods cause harm at scale, rather than trying to prevent them altogether.

“We did what I would say is a sort of safety by design way that allowed us to stay very true to our principles, which is we just don’t take on that work,” Whittaker explained. But this isn’t just at total abdication of their role as proprietors of the platform.

“We’re unwilling to, you know, create a block list or other things to sort of determine what is and is not appropriate. But we’re also unwilling to create new surfaces for harm, right? Like, we recognize that that can be a real issue. So what are we going to do? We’re going to design it so that we’ve minimized or, I believe, eliminated the harm space,” she continued.

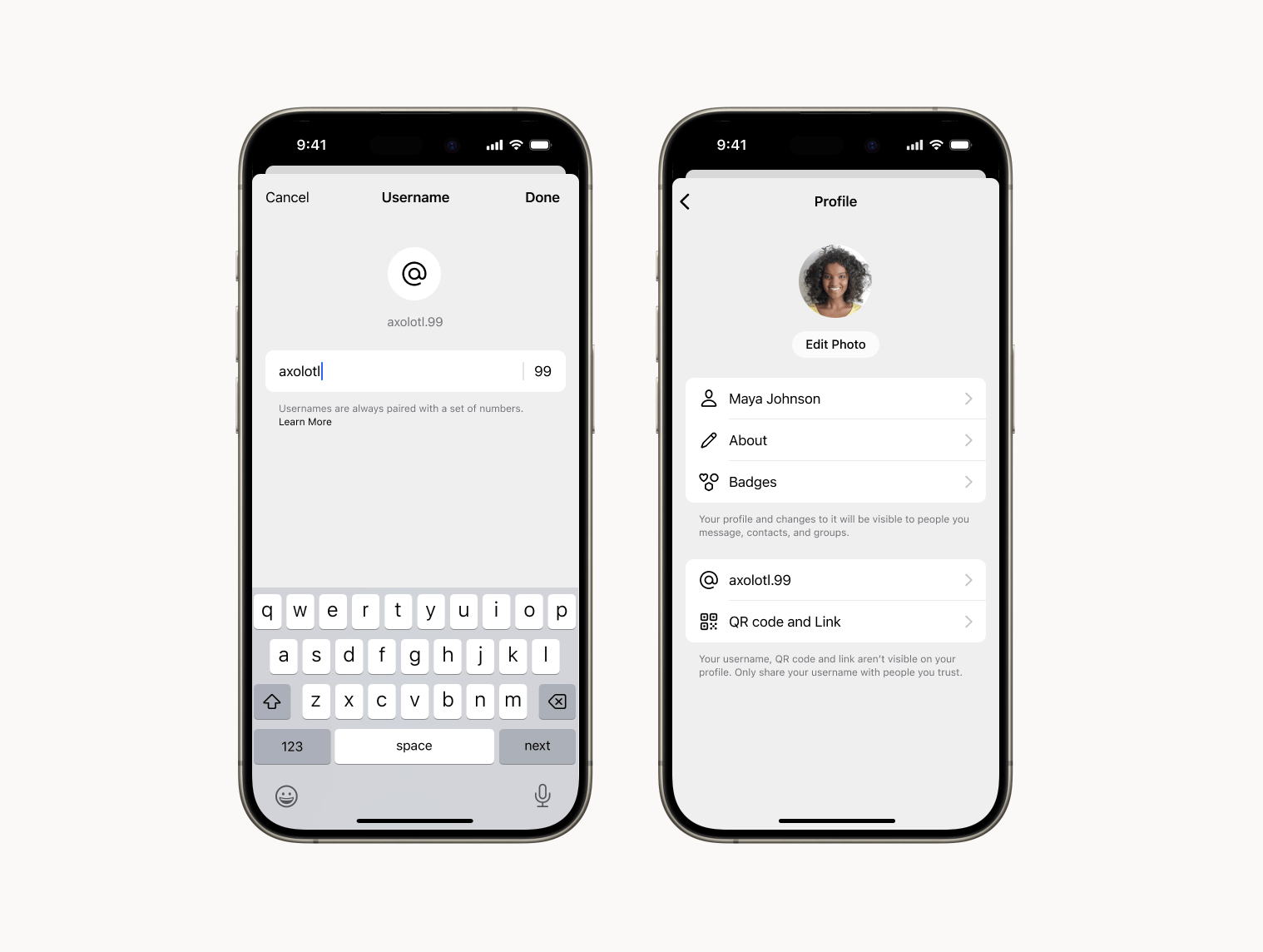

“The user name is not a handle. It’s not shown inside the app; it’s not something we have a directory for. But it replaces the phone number when you go to initiate contact.” (Signal does append numbers to chosen usernames to ensure they are unique.)

In other words, the system is far more limited than the public profiles or spam you might get on other platforms that have usernames as the canonical identifiers for users.

Instead, the username provides a way to simultaneously identify and conceal oneself; someone requesting it gets all the benefits of Signal’s phone number requirement but few of the risks of username exploitations. You only get the username if you ask for it, which shifts responsibility to the users without compromising their needs or discriminatory capacity.

“I think there’s actually kind of a paradigm around safe design with integrity that we’re pushing forward as we add a very essential layer of privacy to the app,” she concluded.

The new feature will be available in the Signal 7.0 client. “And if you’re a beta user, you can go in and claim your username now,” Whittaker added. “If you’re about that.”

And you can watch the full interview below: