Clayton Christensen was an amazing observer of business, and his work on disruption is seminal. His book “The Innovator’s Dilemma” has come to define how we analyze companies that get disrupted by newcomers.

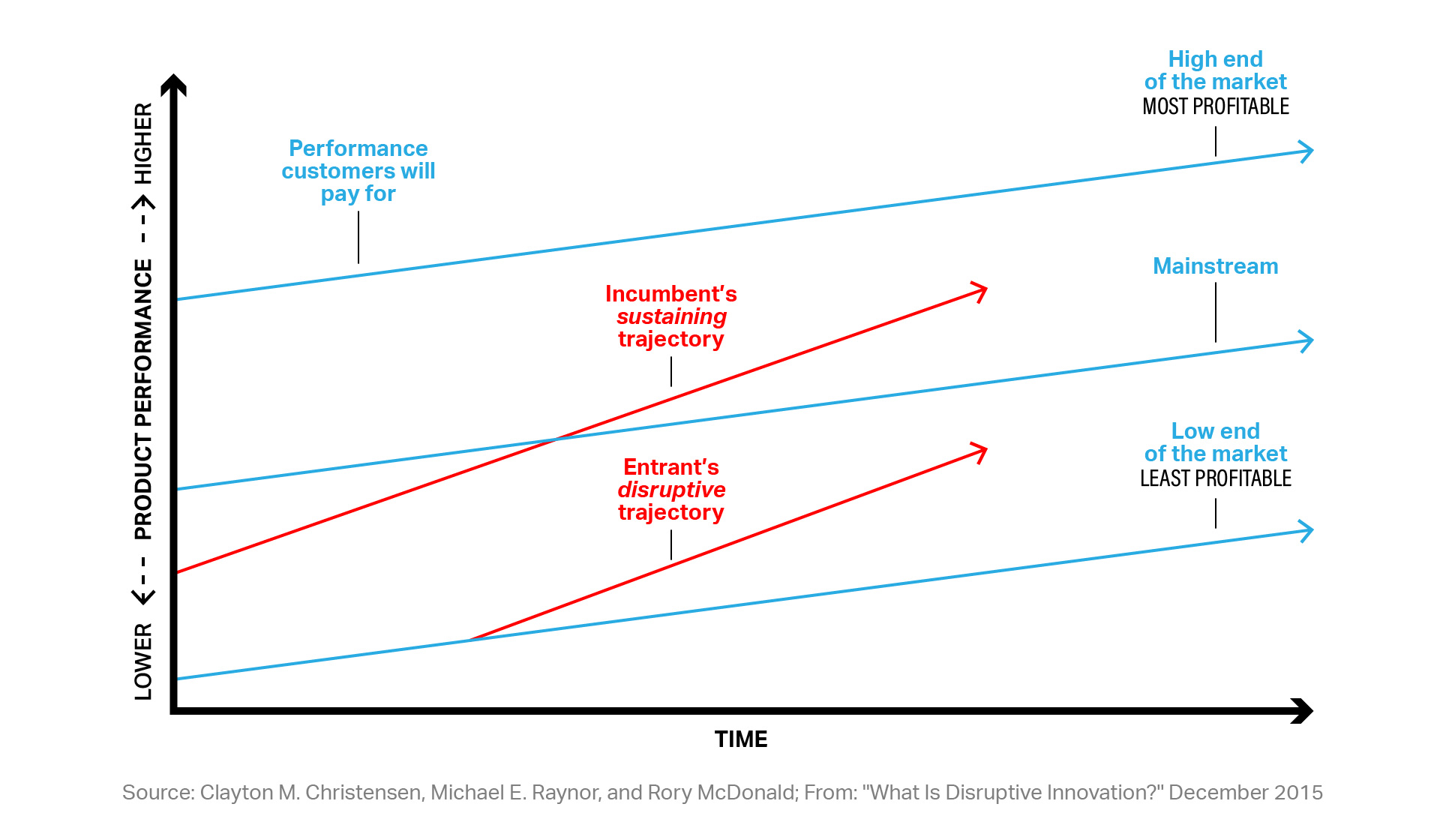

The core of his thesis is that companies focus on their current best customers and improve the product for them while a new entrant comes in with a cheaper product that serves the underserved segment with an inferior product that is good enough — and over time, the inferior product gets better enough to meet the needs of most customers disrupting the incumbent’s core business.

But has he been proven wrong in the last 10 years on many major disruptions? For instance:

- iPhone was more expensive than competitors at launch.

- Tesla was more expensive than most cars for early models, by a lot.

- Nvidia GPUs are way more expensive than Intel and ARM machines.

- OpenAI or GPT4 is not cheap. While search engines are free for unlimited use, GPT is $20 month.

If you build a truly great product, people will happily pay for it. Just check out how well Apple and Tesla have done.

What if the bottom-up cheaper product disrupting the market is a phenomenon limited to commoditized old product categories (think tires and clothes)? Although, one could argue even in those categories the real disruption often starts at the highest end — run flat tires cost more, yoga pants (Lululemon and Alo Yoga) cost more — not less than the older products they replace in use.

The Christensen theory of disruption could be called “inferior disruption theory” — inferior, cheaper, good enough products that disrupt incumbents over time. While this clearly happens, there’s a more powerful model for disruption.

Image Credits: Clayton M. Christensen, Michael E. Raynor, and Rory McDonald

In his own words:

Disruptive innovations, on the other hand, are initially considered inferior by most of an incumbent’s customers. Typically, customers are not willing to switch to the new offering merely because it is less expensive. Instead, they wait until its quality rises enough to satisfy them. Once that’s happened, they adopt the new product and happily accept its lower price. (This is how disruption drives prices down in a market.)

I would like to propose a different disruption model — one that starts at the exact opposite end: superior product disruption.

Superior product disruption

An innovator brings a superior product at a higher price to the market and wins over the top 1% consumers of the product, who are willing to pay a premium. As the product gets more popular, the innovator is able to lower prices due to scale efficiency, cost-effective innovations, and riding cost curves such as Moore’s law over time.

This week, Apple starts taking orders for its Vision Pro, a product priced at $3,499 — about 10x higher than the Meta Quest 2 and 3x higher than the most expensive Meta Quest Pro. Is Apple destined to fail, or have they figured out a better strategy?

Image Credits: Apple

We will find out whether Vision Pro is a winning product and whether the superior product disruption works in this case.

But over the years, we have already seen several products start out as super-expensive, superior or better products win the high end of the market and slowly take market share as the product prices come down with scale, innovation and commoditization.

Tesla

You can now buy a Tesla for $35,000. The first model cost $120,000. As Elon Musk famously laid out in this “secret master plan” document on August 2, 2006:

- Build sports car.

- Use that money to build an affordable car.

- Use that money to build an even more affordable car.

- While doing above, also provide zero-emission electric power generation options.

- Don’t tell anyone.

It’s been 17 years of Tesla doing literally the above. But Tesla is not the only one.

Nvidia

It has consistently produced higher end products with higher end specs for what they call the “tech enthusiast.” It continues to this day with their high-end H100 GPUs.

Over time, they continually keep innovating at the highest end.

Jensen’s insight: Most of the profits are at the high end of the market.

It was true for its landmark Riva chip — building the highest end product, and consequently at the highest price point the market could afford.

Where was Clayton Christensen right?

I believe Christensen got lots of things right in his book — primarily the tendency of incumbents to cater to the needs of existing customers in existing markets at the price points they are familiar with.

If you are selling a product that is no longer as innovative — think petroleum-powered cars in the 1980s — you are likely to get disrupted by someone who builds a good enough car at a cheaper price. Over time, the Japanese car manufacturers who started out with inferior products became better and better at manufacturing — and design — and now produce some of the best cars in the world at any price point.

Cell phones vs. landline phones

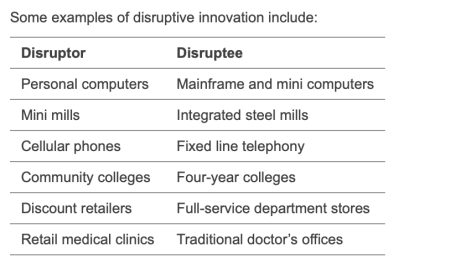

In his original book, Clayton lays out a few examples of disruption:

Image Credits: Christensen

It’s not clear to me at all that cellular phones are worse than landlines. I would argue it’s a vastly superior product — and clearly sold at a much higher price point.

The PC was certainly cheaper than the mainframe but mainframes could be shared and PCs could not. In fact, most people mocked PCs for being too expensive.

In both cases, it was the novel superior product that won out.

What is the right strategy for winning?

I think frameworks like Innovator’s Dilemma — and many other business strategy frameworks like Blue Ocean/Red Ocean that tell you to avoid competitive markets and so on — are great for learning. If you are a big company CEO or executive, it may help you watch your back so you don’t get disrupted in your core markets.

But when it comes to really building a disruptive new business, my advice to founders and product managers is simple:

Build a better product.

Steve Jobs was right — you have to obsessively care about the product. Jeff Bezos is right — you have to obsessively care about the customer. And Elon Musk is right — you have to question everything from first principles.

If you do these things and build an amazing product, it may turn out to be a product that is 10x cheaper — digital photography is effectively free compared to film, electric cars total cost of ownership is much lower — or it may turn out to be an expensive product for the high end of the market.

If you build a truly great product, people will happily pay for it. Just check out how well Apple and Tesla have done.

In a few weeks, we will get to test this theory again — with a high-end product built with few compromises to deliver a new kind of reality.