Substack has industry-leading newsletter tools and a platform that independent writers flock to, but its recent content moderation missteps could prove costly.

In late November, the Atlantic reported that a search of the publishing platform “turns up scores of white-supremacist, neo-Confederate, and explicitly Nazi newsletters on Substack — many of them apparently started in the past year.” That included 16 newsletters with explicit Nazi imagery, including swastikas and the black sun symbol often employed by modern white supremacists. The imagery appeared in prominent places on Substack, including in some newsletter logos — places that the kind of algorithmic moderation systems standard on traditional social media platforms could easily detect.

Substack writers took note, and a letter collecting the signatures from almost 250 authors on the platform pressed the company to explain its decision to publish and profit from neo-Nazis and other white supremacists. “Is platforming Nazis part of your vision of success?” they wrote. “Let us know — from there we can each decide if this is still where we want to be.”

At the time, Substack CEO Hamish McKenzie addressed the mounting concerns about Substack’s aggressively hands-off approach in a note on the website, observing that while “we don’t like Nazis either,” Substack would break with content moderation norms by continuing to host extremist content, including newsletters by Nazis and other white supremacists.

“We will continue to actively enforce those rules while offering tools that let readers curate their own experiences and opt in to their preferred communities,” McKenzie wrote. “Beyond that, we will stick to our decentralized approach to content moderation, which gives power to readers and writers.”

McKenzie overlooks or is not concerned with the way that amplifying hate — in this case, nothing short of self-declared white supremacy and Nazi ideology — serves to disempower, drive away and even silence the targets of that hate. Hosting even a sliver of that kind of extremism sends a clear message that more of it is allowed.

McKenzie went on to state that the company draws the line at “incitements to violence” — which by Substack’s definition must necessarily be intensely specific or meet otherwise unarticulated criteria, given its decision to host ideologies that by definition seek to eradicate racial and ethnic minorities and establish a white ethnostate.

In her own endorsement of the Substack authors’ open letter, Margaret Atwood observed the same. “What does ‘Nazi’ mean, or signify?” Atwood asked. “Many things, but among them is ‘Kill all Jews’ . . . If ‘Nazi’ does not mean this, what does it mean instead? I’d be eager to know. As it is, anyone displaying the insignia or claiming the name is in effect saying ‘Kill all Jews.'”

None of this comes as a surprise. Between the stated ethos of the company’s leadership and prior controversies that drove many transgender users away from the platform, Substack’s lack of expertise and even active disinterest in the most foundational tools of content moderation were pretty clear early on in its upward trajectory.

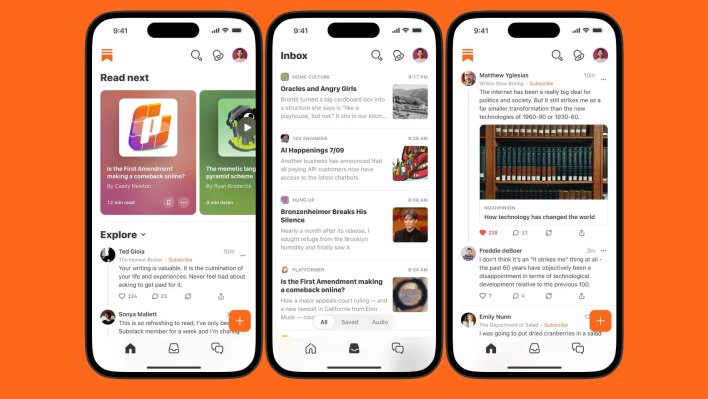

Earlier last year, Substack CEO Chris Best failed to articulate responses to straightforward questions from the Verge editor-in-chief Nilay Patel about content moderation. The interview came as Substack launched its own Twitter (now X)-like microblogging social platform, known as Notes. Best ultimately took a floundering defensive posture that he would “not engage in speculation or specific ‘would you allow this or that, content,'” when pressed to answer if Substack would allow racist extremism to proliferate.

In a follow-up post, McKenzie made a flaccid gesture toward correcting the record. “We messed that up,” he wrote. “And just in case anyone is ever in any doubt: we don’t like or condone bigotry in any form.” The problem is that Substack, in spite of its defense, functionally did, even allowing a monetized newsletter from Unite the Right organizer and prominent white supremacist Richard Spencer. (Substack takes a 10% cut of the revenue from writers who monetize their presence on the platform.)

Substack authors are at a crossroads

In the Substack fallout, which is ongoing, another wave of disillusioned authors is contemplating jumping ship from Substack, substantial readerships in tow. “I said I’d do it and I did it, so Today in Tabs is finally free of Our Former Regrettable Platform, who did not become any less regrettable over the holidays,” Today in Tabs author Rusty Foster wrote of his decision to switch to Substack competitor Beehiiv.

From his corner of Substack, Platformer author and tech journalist Casey Newton continues to press the company to crack down on Nazi content, including a list of accounts that the Platformer team itself identified and provided that appear to violate the company’s rules against inciting violence. Newton, who has tracked content moderation on traditional social media sites for years, makes a concise case for why Substack increasingly has more in common with those companies — the Facebooks, Twitters and YouTubes — than it does with, say, DreamHost:

[Substack] wants to be seen as a pure infrastructure provider — something like Cloudflare, which seemingly only has to moderate content once every few years. But Cloudflare doesn’t recommend blogs. It does not send out a digest of websites to visit. It doesn’t run a text-based social network, or recommend posts you might like right at the top.

. . . Turning a blind eye to recommended content almost always comes back to bite a platform. It was recommendations on Twitter, Facebook, and YouTube that helped turn Alex Jones from a fringe conspiracy theorist into a juggernaut that could terrorize families out of their homes. It was recommendations that turned QAnon from loopy trolling on 4Chan into a violent national movement. It was recommendations that helped to build the modern anti-vaccine movement.

The moment a platform begins to recommend content is the moment it can no longer claim to be simple software.

On Monday, Substack agreed to remove “several publications that endorse Nazi ideology” from Platformer’s list of flagged accounts. In spite of ongoing scrutiny, the company maintained that it would not begin proactively removing extremist and neo-Nazi content on the platform, according to Platformer. Substack is attempting to thread the needle by promising that it is “actively working on more reporting tools” so users can flag content that might violate its content guidelines — and effectively do the company’s most basic moderation work for it, itself a time-honored social platform tradition.

More polished on many counts than a Rumble or a Truth Social, Substack’s useful publisher tools and reasonable profit share have lured weary authors from across the political spectrum eager for a place to hang their hat. But until Substack gets more serious about content moderation, it runs the risk of losing mainstream writers — and their subscribers — who are rightfully concerned that its executives insist on keeping a light on for neo-Nazis and their ilk.

Substack has long offered a soft landing spot for writers and journalists striking out on their own, but the company’s latest half-measure is unlikely to sit well with anyone worried about the platform’s policies. It’s unfortunate that Substack’s writers and readers now have to grapple with yet another form of avoidable precarity in the publishing world.