Most companies developing AI models, particularly generative AI models like ChatGPT, GPT-4 Turbo and Stable Diffusion, rely heavily on GPUs. GPUs’ ability to perform many computations in parallel make them well-suited to training — and running — today’s most capable AI.

But there simply aren’t enough GPUs to go around.

Nvidia’s best-performing AI cards are reportedly sold out until 2024. The CEO of chipmaker TSMC was less optimistic recently, suggesting that the shortage of AI GPUs from Nvidia — as well as chips from Nvidia’s rivals — could extend into 2025.

So Microsoft’s going its own way.

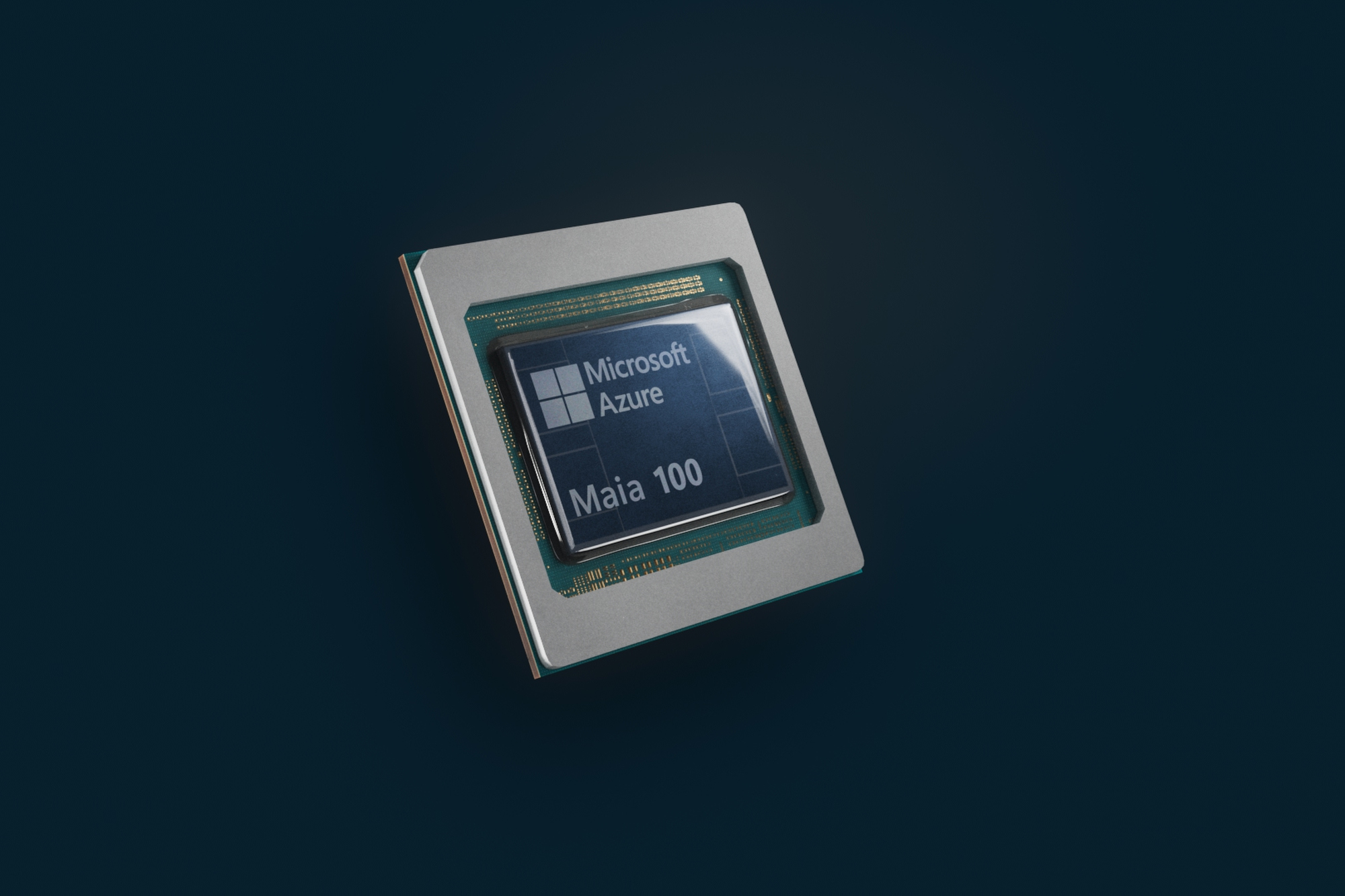

Today at its 2023 Ignite conference, Microsoft unveiled two custom-designed, in-house and data center-bound AI chips: the Azure Maia 100 AI Accelerator and the Azure Cobalt 100 CPU. Maia 100 can be used to train and run AI models, while Cobalt 100 is designed to run general purpose workloads.

Image Credits: Microsoft

“Microsoft is building the infrastructure to support AI innovation, and we are reimagining every aspect of our data centers to meet the needs of our customers,” Scott Guthrie, Microsoft cloud and AI group EVP, was quoted as saying in a press release provided to TechCrunch earlier this week. “At the scale we operate, it’s important for us to optimize and integrate every layer of the infrastructure stack to maximize performance, diversify our supply chain and give customers infrastructure choice.”

Both Maia 100 and Cobalt 100 will start to roll out early next year to Azure data centers, Microsoft says — initially powering Microsoft AI services like Copilot, Microsoft’s family of generative AI products, and Azure OpenAI Service, the company’s fully managed offering for OpenAI models. It might be early days, but Microsoft assures that the chips aren’t one-offs. Second-generation Maia and Cobalt hardware is already in the works.

Built from the ground up

That Microsoft created custom AI chips doesn’t come as a surprise, exactly. The wheels were set in motion some time ago — and publicized.

In April, The Information reported that Microsoft had been working on AI chips in secret since 2019 as part of a project code-named Athena. And further back, in 2020, Bloomberg revealed that Microsoft had designed a range of chips based on the ARM architecture for data centers and other devices, including consumer hardware (think the Surface Pro).

But the announcement at Ignite gives the most thorough look yet at Microsoft’s semiconductor efforts.

First up is Maia 100.

Microsoft says that Maia 100 — a 5-nanometer chip containing 105 billion transistors — was engineered “specifically for the Azure hardware stack” and to “achieve the absolute maximum utilization of the hardware.” The company promises that Maia 100 will “power some of the largest internal AI [and generative AI] workloads running on Microsoft Azure,” inclusive of workloads for Bing, Microsoft 365 and Azure OpenAI Service (but not public cloud customers — yet).

Image Credits: Microsoft

That’s a lot of jargon, though. What’s it all mean? Well, to be quite honest, it’s not totally obvious to this reporter — at least not from the details Microsoft’s provided in its press materials. In fact, it’s not even clear what sort of chip Maia 100 is; Microsoft’s chosen to keep the architecture under wraps, at least for the time being.

In another disappointing development, Microsoft didn’t submit Maia 100 to public benchmarking test suites like MLCommons, so there’s no comparing the chip’s performance to that of other AI training chips out there, such as Google’s TPU, Amazon’s Tranium and Meta’s MTIA. Now that the cat’s out of the bag, here’s hoping that’ll change in short order.

One interesting factoid that Microsoft was willing to disclose is that its close AI partner and investment target, OpenAI, provided feedback on Maia 100’s design.

It’s an evolution of the two companies’ compute infrastructure tie-ups.

In 2020, OpenAI worked with Microsoft to co-design an Azure-hosted “AI supercomputer” — a cluster containing over 285,000 processor cores and 10,000 graphics cards. Subsequently, OpenAI and Microsoft built multiple supercomputing systems powered by Azure — which OpenAI exclusively uses for its research, API and products — to train OpenAI’s models.

“Since first partnering with Microsoft, we’ve collaborated to co-design Azure’s AI infrastructure at every layer for our models and unprecedented training needs,” Altman said in a canned statement. “We were excited when Microsoft first shared their designs for the Maia chip, and we’ve worked together to refine and test it with our models. Azure’s end-to-end AI architecture, now optimized down to the silicon with Maia, paves the way for training more capable models and making those models cheaper for our customers.”

I asked Microsoft for clarification, and a spokesperson had this to say: “As OpenAI’s exclusive cloud provider, we work closely together to ensure our infrastructure meets their requirements today and in the future. They have provided valuable testing and feedback on Maia, and we will continue to consult their roadmap in the development of our Microsoft first-party AI silicon generations.”

We also know that Maia 100’s physical package is larger than a typical GPU’s.

Microsoft says that it had to build from scratch the data center server racks that house Maia 100 chips, with the goal of accommodating both the chips and the necessary power and networking cables. Maia 100 also required a unique liquid-based cooling solution since the chips consume a higher-than-average amount of power and Microsoft’s data centers weren’t designed for large liquid chillers.

Image Credits: Microsoft

“Cold liquid flows from [a ‘sidekick’] to cold plates that are attached to the surface of Maia 100 chips,” explains a Microsoft-authored post. “Each plate has channels through which liquid is circulated to absorb and transport heat. That flows to the sidekick, which removes heat from the liquid and sends it back to the rack to absorb more heat, and so on.”

As with Maia 100, Microsoft kept most of Cobalt 100’s technical details vague in its Ignite unveiling, save that Cobalt 100’s an energy-efficient, 128-core chip built on an Arm Neoverse CSS architecture and “optimized to deliver greater efficiency and performance in cloud native offerings.”

Image Credits: Microsoft

Arm-based AI inference chips were something of a trend — a trend that Microsoft’s now perpetuating. Amazon’s latest data center chip for inference, Graviton3E (which complements Inferentia, the company’s other inference chip), is built on an Arm architecture. Google is reportedly preparing custom Arm server chips of its own, meanwhile.

“The architecture and implementation is designed with power efficiency in mind,” Wes McCullough, CVP of hardware product development, said of Cobalt in a statement. “We’re making the most efficient use of the transistors on the silicon. Multiply those efficiency gains in servers across all our datacenters, it adds up to a pretty big number.”

A Microsoft spokesperson said that Cobalt 100 will power new virtual machines for customers in the coming year.

But why?

So Microsoft’s made AI chips. But why? What’s the motivation?

Well, there’s the company line — “optimizing every layer of [the Azure] technology stack,” one of the Microsoft blog posts published today reads. But the subtext is, Microsoft’s vying to remain competitive — and cost-conscious — in the relentless race for AI dominance.

The scarcity and indispensability of GPUs has left companies in the AI space large and small, including Microsoft, beholden to chip vendors. In May, Nvidia reached a market value of more than $1 trillion on AI chip and related revenue ($13.5 billion in its most recent fiscal quarter), becoming only the sixth tech company in history to do so. Even with a fraction of the install base, Nvidia’s chief rival, AMD, expects its GPU data center revenue alone to eclipse $2 billion in 2024.

Microsoft is no doubt dissatisfied with this arrangement. OpenAI certainly is — and it’s OpenAI’s tech that drives many of Microsoft’s flagship AI products, apps and services today.

In a private meeting with developers this summer, Altman admitted that GPU shortages and costs were hindering OpenAI’s progress; the company just this week was forced to pause sign-ups for ChatGPT due to capacity issues. Underlining the point, Altman said in an interview this week with the Financial Times that he “hoped” Microsoft, which has invested over $10 billion in OpenAI over the past four years, would increase its investment to help pay for “huge” imminent model training costs.

Microsoft itself warned shareholders earlier this year of potential Azure AI service disruptions if it can’t get enough chips for its data centers. The company’s been forced to take drastic measures in the interim, like incentivizing Azure customers with unused GPU reservations to give up those reservations in exchange for refunds and pledging upwards of billions of dollars to third-party cloud GPU providers like CoreWeave.

Should OpenAI design its own AI chips as rumored, it could put the two parties at odds. But Microsoft likely sees the potential cost savings arising from in-house hardware — and competitiveness in the cloud market — as worth the risk of preempting its ally.

One of Microsoft’s premiere AI products, the code-generating GitHub Copilot, has reportedly been costing the company up to $80 per user per month partially due to model inferencing costs. If the situation doesn’t turn around, investment firm UBS sees Microsoft struggling to generate AI revenue streams next year.

Of course, hardware is hard, and there’s no guarantee that Microsoft will succeed in launching AI chips where others failed.

Meta’s early custom AI chip efforts were beset with problems, leading the company to scrap some of its experimental hardware. Elsewhere, Google hasn’t been able to keep pace with demand for its TPUs, Wired reports — and ran into design issues with its newest generation of the chip.

Microsoft’s giving it the old college try, though. And it’s oozing with confidence.

“Microsoft innovation is going further down in the stack with this silicon work to ensure the future of our customers’ workloads on Azure, prioritizing performance, power efficiency and cost,” Pat Stemen, a partner program manager on Microsoft’s Azure hardware systems and infrastructure team, said in a blog post today. “We chose this innovation intentionally so that our customers are going to get the best experience they can have with Azure today and in the future …We’re trying to provide the best set of options for [customers], whether it’s for performance or cost or any other dimension they care about.”