WeWork’s bankruptcy filing has arrived. The well-known flexible office-space company has filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection in the United States and Canada, seeking to convert certain debts to equity investments, and “further rationalize its commercial office lease portfolio.”

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

In fewer words: WeWork wants out of some of its leases while keeping its lights on so it can shed liabilities and get its business to a point where it can self-sustain. For more on the nuances of the filing, see TechCrunch’s coverage of the news.

This morning, let’s talk about WeWork’s economics. Did the company’s business ever make sense? To answer that question, we’ll go over its S-1 filings, its SPAC deal and its early earnings reports.

This morning, let’s talk about WeWork’s economics. Did the company’s business ever make sense? To answer that question, we’ll go over its S-1 filings, its SPAC deal and its early earnings reports.

A history of unworkable economics

To start, we have to rewind the clock to 2019.

There was a time when WeWork was a hot, venture-backed company. Heading into its IPO filing, the market knew that the company was quite unprofitable, but as with all private companies, WeWork’s lack of clearly delineated results made it seem more appealing. It was not until the company filed to go public that we really learned how it had financed its impressive growth rates.

And grow WeWork did. It went from revenue of $436.1 million in 2016 to $886 million in 2017, $1.82 billion in 2018, and $1.54 billion in the first half of 2019.

That growth came at a massive cost. The company’s operating losses swelled from $931.8 million in 2017 to $1.69 billion in 2018, and then to $1.37 billion in the first half of 2019. In short, WeWork grew quickly but had to burn piles of cash to do it.

Which begs the question: How was the company losing so much money on something as well-understood as office space leasing? WeWork did spend too much time and money on efforts that had little bearing on its core operations, but what mattered more is the fact that its business was fundamentally garbage when it tried to go public.

Let me explain:

- H1 2019 revenue: $1.54 billion.

- H1 2019 membership and service revenue: $1.35 billion.

- H1 2019 location operating expenses: $1.23 billion.

- H1 2019 depreciation and amortization: $255.9 million.

- H1 2019 location operating expenses + depreciation and amortization: $1.49 billion.

In short, WeWork’s core business was operating at a gross margin loss after the depreciation and amortization costs were added to its location operating costs. When you compare that lackluster profitability picture with the company’s staggering costs of $2.09 billion in the first half of 2019, you begin to see how it came to lose all that money.

So, what did WeWork do? It came up with new and better math to make itself appear more profitable. Here’s the company describing a much kinder metric that it preferred to more traditional figures:

We define “contribution margin including non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost” as membership and service revenue less location operating expenses (both as determined and reported in accordance with GAAP), adjusted to exclude non-cash stock-based compensation expense included in location operating expenses. We define “contribution margin excluding non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost” as contribution margin including non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost further adjusted to exclude non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost.

If you can parse that, congratulations. It isn’t a simple concept, but in essence WeWork found a way to make it look like its core business — running and leasing office space — did generate some margins. Its “contribution margin including non-cash GAAP straight-line lease cost” came to $339.9 million in H1 2019, from the aforementioned $1.35 billion in membership and service revenue. That’s not terrible gross margin for a non-tech product, but given the financial jiggering it took to get there, few investors were impressed at the time.

What’s worse, the company was igniting entire bales of cash to generate that super-adjusted margin from its core business. In just the first half of 2019, WeWork burned $198.7 million in cash to fund its operations, and another $2.36 billion to fund its investing work. That was counterbalanced by massive investing inflows, but the company itself was cash-hungry, increasingly unprofitable and had ambiguous unit economics at best.

Then, as we all recall, WeWork eventually pulled its IPO after a few S-1/A filings and everyone forgot about it for a while.

Enter the SPAC.

The 2021 pitch

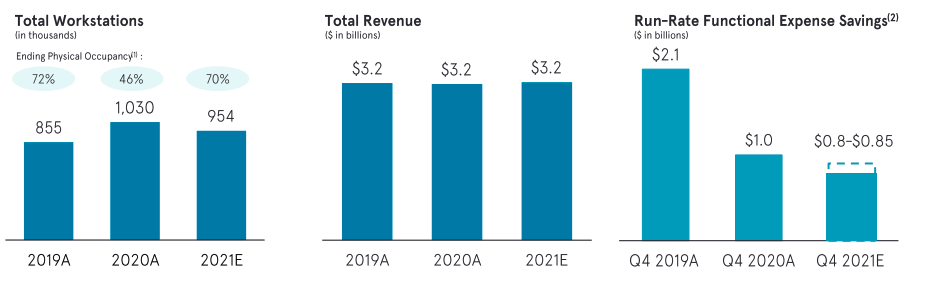

Cognizant of the weaknesses that everyone noticed when it first tried to go public, WeWork stressed “recent cost optimization efforts” that would help it achieve “profitable growth in 2021 and beyond” in its SPAC presentation.

Here’s how the company described its COVID-era performance at the time:

Image Credits: WeWork

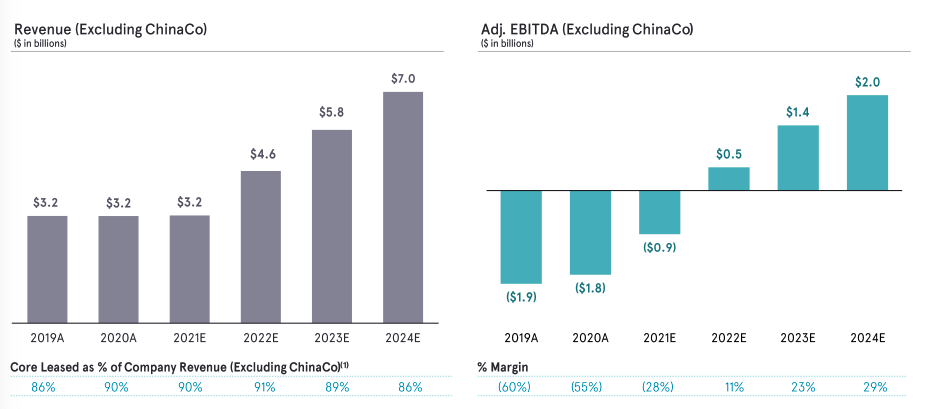

That was the past. How did WeWork see its future bearing out? It anticipated rapid revenue growth and rising adjusted EBITDA:

Image Credits: WeWork

Another chart pointed to the fourth quarter of 2021 as the point where the company would break even on an adjusted EBITDA basis, and the company said it had a “clear path” to that result.

So, what happened?

Whoops

In its first quarter as a public company, WeWork posted Q2 revenues of $593 million, an adjusted EBITDA loss of $449 million, a net loss of $923 million, a free cash deficit of $649 million, and $1.6 billion in cash.

Sure, you must be thinking, that looks absolutely terrible, but the company forecasted just $900 million in adjusted EBITDA losses in the year, so surely things got better?

The numbers did improve somewhat in the third quarter: Revenue came in at $661 million, adjusted EBITDA loss was $356 million, free cash deficit of $430 million, and $1.2 billion in cash.

To hit its adjusted EBITDA target for the year, however, WeWork would have to do very well in the fourth quarter. Did that happen? Nope. Total revenue of $718 million led to an adjusted EBITDA loss of $283 million, and a free cash deficit of $467 million.

In 2021, WeWork ended the year with revenues of $2.57 billion, adjusted EBITDA losses of $1.53 billion, and net loss of $4.63 billion. Comparing those figures with what we saw in its SPAC deck, there’s an incredibly massive divergence.

The next year was only slightly better. Revenue of $3.25 billion led to an operating loss of $1.59 billion, and adjusted EBITDA loss of $477 million. So much for flipping to adjusted profitability in late 2021.

Why did the ship not right itself? Why did the plan fail, even with the capital raised from its SPAC debut on the public markets?

In 2022, WeWork had membership and service revenue of $3.20 billion. Against that, it had location operating expenses of $2.91 billion. Even before we consider depreciation and amortization expenses for those spaces, the company’s core product had low-brow margins even after years of work to improve its operating base. All that work got it the sort of margins you expect to achieve from selling milk.

So, after all those years, all the billions in capital, all the promises, the hype, a failed IPO cycle, a SPAC offering, and time after an IPO to turn the business around, WeWork ended up as a low-margin company that was torching cash.

The lesson

I have learned several things from WeWork’s train wreck:

Excessive cleverness usually fails

Do you know why WeWork’s adjusted EBITDA results were so much better than its operating losses? Partly because the company discounted “depreciation and amortization” in the adjusted profitability metric. Why? Because it’s a non-cash charge.

Sure, but the figure was still depreciation and amortization off spent cash. The company was stuffing losses into its investing cash flow — as best as I can tell, but please enjoy reading 8 trillion pages of historical SEC filings and investor presentations — only to, voilà, make them disappear in its income statement. Financial sleight of hand is just that and it is nearly always too cute by far.

Don’t scale a low-margin business too quickly

We’ve seen this happen a bunch in recent years: Sweetgreen, Rent the Runway, the list goes on. Many companies can grow quickly, but many also don’t have the economics to support that rapid growth if external capital dries up.

The reason why some software businesses can scale like gods is that their core economics shit gold. Sure, SaaS companies burn cash as they expand, but every dollar of recurring revenue they bring in puts three quarters’ worth of gross profit in their pockets. That can pencil out, even if it is costly. That model just doesn’t work when the gross margins in question are, to be candid, trash.

Stick to tech

VCs and other private-market investors should not convince themselves that a quickly-growing company that is technology-adjacent is actually a tech company. This is an easy trap to fall into. I do not hold that I would do better were I to be a venture investor. I would do worse, in all likelihood. But for the pros out there, growth is not equal, even if you really, really wish that it was.

I keep thinking that we’ve closed the book on WeWork, but it keeps coming back. Perhaps it will become a lean, office rental company once the bankruptcy process runs through. That model can make a buck, just not $47 billion of them.