The year 2023 doesn’t sound like a good time to be a wind power startup. Take Ørsted, the Danish wind company: It recently announced that it would be taking a charge of up to $5.6 billion this year, partly because of various wind projects being canceled, including a large one off the coast of New Jersey. The decision was driven by inflation, high interest rates, and supplier delays, the company said.

Bad timing indeed, unless you’re a company that thinks the old way to design wind farms is all wrong.

“Wind turbines are big and getting bigger. That limits where they can be deployed. It limits site development: You can’t go to the mountains. It’s really hard to go to low wind sites; most of the high wind sites have been built,” said Neal Rickner, CEO of AirLoom Energy and former COO of Makani, the Google X wind power spinout. “So if you’re looking for additional sites to build, [traditional] horizontal turbines become less and less attractive.”

AirLoom is what you would call a nontraditional form of wind power, and naturally, it seeks to fill the gaps Rickner listed while also bringing the price down significantly. The startup has been operating under the radar (until now, at least) and it already has a small prototype up and running at its headquarters adjacent to the regional airport just outside Laramie, Wyoming.

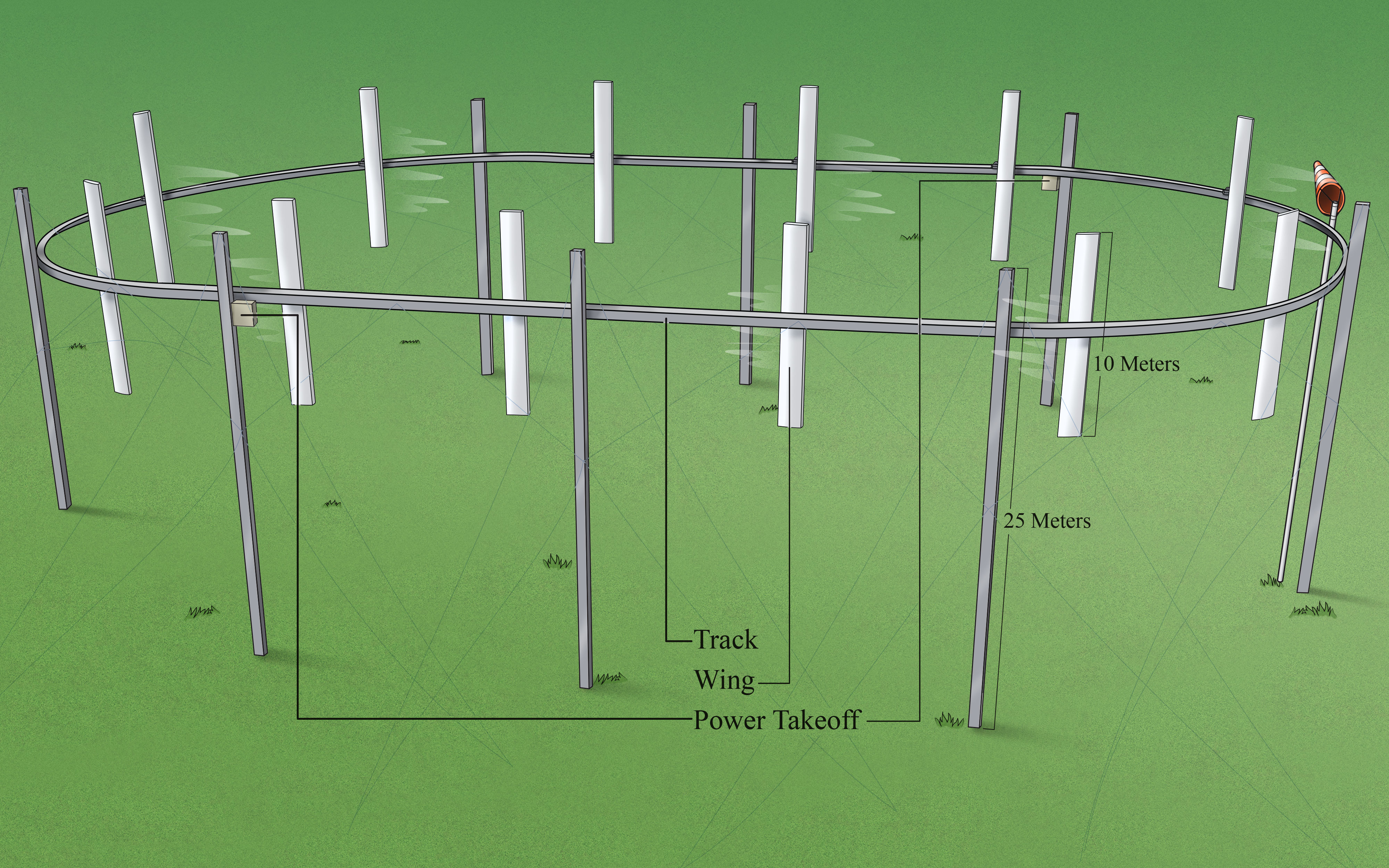

The prototype works like this: A cable runs in a track atop a series of 25-meter (82 foot) tall poles arranged in an oval. Vertically oriented, 10-meter (33-foot) long blades are attached to the cable to intercept the wind as it travels down both the home and the backstretch of the cable’s track. A power takeoff sits on one of the poles, connecting the system to the grid.

AirLoom’s president and co-founder, Robert Lumley, first sketched the concept on a napkin a decade ago and spent the intervening years working out the details and starting the company. He was inspired by kiteboarding, a hobby of his, while attending a wind energy conference in Berlin.

Makani was also inspired by kites, but in a different way. The company devised an aerial platform for wind turbines that would be tethered to the ground by a cable. The hope was to eliminate the need for costly steel towers and concrete foundations and replace them with cheap cables and software that would automate the kite’s flights. The entire operation proved to be overly complex, Rickner said. Makani folded in 2020.

The simplicity of the AirLoom system is part of what attracted Rickner to the company. “There’s nothing magical. We understand the physics at play here,” he told TechCrunch+.

The physics appear promising for AirLoom, too. Today’s wind turbines can extract about 50% of the energy present in the wind, which is not bad given that the theoretical limit is about 60%. AirLoom captures about 57%, Rickner said.

An illustration of the different parts of AirLoom’s device. Image Credits: AirLoom Energy

“The question then becomes: Can you build a system that is low friction, where you don’t get high electrical losses from transferring from kinetic to mechanical to electrical?” That’s what the company is planning to do with the $4 million seed round it recently raised. The round was led by Breakthrough Energy Ventures and saw participation from Lowercarbon Capital, MCJ Collective and others.

Fortunately for AirLoom, low-friction tracks are understood well. “We’re going to learn from the railroad industry, and we’re going to use lessons from the roller-coaster industry. Rather than creating new novel tech, we’re going to create things by putting pieces together from known engineered products that have been on the market for a while,” Rickner said.

The goal is to lower the price of wind power to $13 per megawatt-hour. If AirLoom can do it, it would undercut traditional onshore wind, which can run anywhere from $24 to $75 per megawatt-hour, according to Lazard, by 50% or more.

A big part of the cost savings would come from the smaller, more modular approach the startup is taking. Today’s wind turbines are massive pieces of equipment. The height of their hubs, which dictates the size of the tower, averages around 100 meters (328 feet), while the rotors have a diameter of 130 meters (426 feet). Not only does that complicate installation, but it also makes transporting the parts especially challenging. The rotors, for example, require specialized trailers.

In comparison, AirLoom’s single largest piece would be the 30-meter tower. That’s longer than a standard tractor-trailer, but far shorter than a typical turbine.

The other way the company hopes to lower the cost is by increasing the density of wind-harvesting equipment. Large turbines need to be spaced far apart so their wakes don’t disrupt the productivity of other turbines downwind. AirLoom’s shorter blades mean each track can be placed closer together, potentially boosting the energy density anywhere from twice to ten times more than traditional wind farms.

“In the Midwest, you have these mile-square plots of farmland. There’s no reason why we couldn’t do a full-mile frontage across that land,” Rickner said. The grid connection could happen at the roadside, minimizing disruption to a farmer’s or rancher’s land.

The company still has some tests to run before that happens, of course. Rickner is aiming to complete a 1-megawatt pilot in 2026, followed by a 10-megawatt or larger installation. The U.S. Department of Defense has also expressed interest since the system could be modular enough for soldiers to install at forward operating bases.

It all sounds promising, but AirLoom has a steep road ahead. Plenty of alternative wind technologies have been developed over the years, but none has been able to unseat the traditional, three-bladed turbine. Still, there’s no harm in trying, and Rickner’s experience helping to run Makani appears to have made him sensitive to taking too many risks along the way.

It’s likely that AirLoom will be able to get its pilot up and running. Whether it attracts large customers is less a problem of technical accomplishment and more related to risk. Can the company’s tracks withstand 24/7 operation in harsh conditions? Will an installation’s operations and maintenance costs be less than existing wind farms’? The answers to those questions will likely dictate AirLoom’s ultimate success.

Well, that and interest rates. The fact that the company is seeking solutions from existing industries will certainly reduce the company’s risk profile. It might be enough to help them reinvent the wind farm in the process.