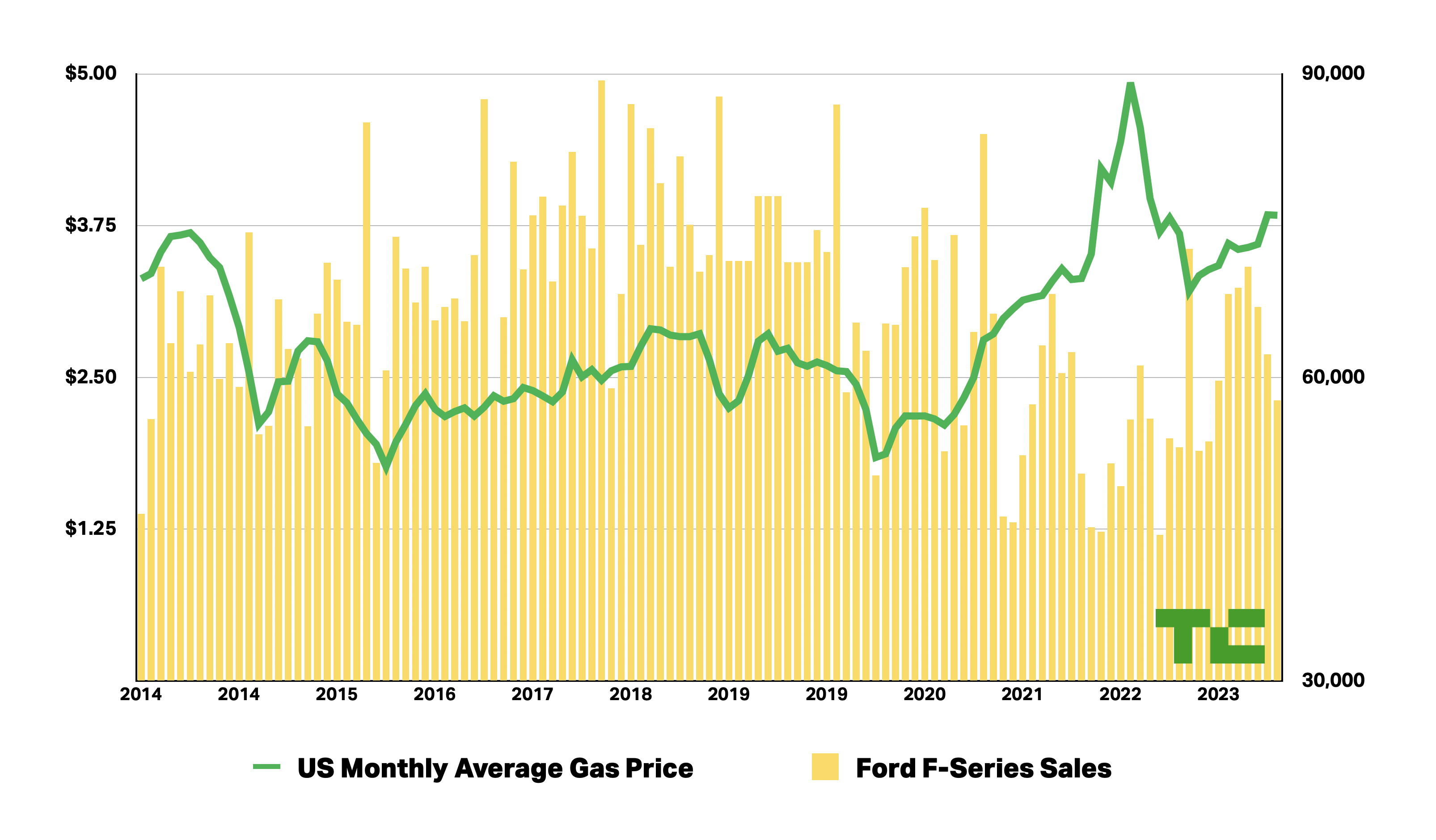

Consumers in the U.S. have the memory of a goldfish.

When gas prices are up, they seek out more fuel-efficient transportation. But when they’re down, they rush to buy the biggest truck possible. Just take a look at Ford F-Series sales data from the last decade juxtaposed with average monthly gas prices.

Image Credits: Tim De Chant/TechCrunch+

See? Goldfish.

It turns out U.S. automakers resemble their customer base. A few years ago, they were bullish on electric vehicles. But now, after just a couple years of serious investment, they’re starting to get cold feet.

Ford and GM, in particular, have said that they’re just responding to their customers’ needs. And maybe they are! Some consumers remain wary because EV charging still sucks. Others have been scared off by high prices. (Arguably, these are both self-inflicted wounds: Legacy automakers have refused to consider charging a key part of the ownership experience, and Ford and GM have continually hiked EV prices in a way that’s out of step with the market.)

Such customer responsiveness can be an asset in normal times, allowing companies to adjust their product lines to ride the ups and downs of the market. Yet in times of transition, when the future is in flux, it can be a terrible way to run a business.

Legacy automakers have long said that their profitable model lines would be a strength as the market transitions to electric vehicles. All three companies have announced that they’d be investing billions in developing EVs and making the batteries that power them, and it would appear that the plan is working out just fine.

Over the last decade, automakers have flocked to crossovers, SUVs and pickup trucks, three segments that are the most profitable. U.S. automakers have gone further than most. Ford even went as far as to stop producing mass market cars, focusing instead on crossovers, SUVs and pickups with the occasional Mustang coupe thrown in for branding purposes.

How’s it been working out? Pretty well, actually. Ford reported $1.2 billion in profit for Q3, not bad given headwinds induced by the UAW strike. GM did better, raking in $3.1 billion in the same quarter. Stellantis doesn’t generally announce its quarterly earnings until November, but it had a gangbuster first half of the year, posting $12.1 billion in profit.

So why have Ford and GM decided to pump the brakes on their EV plans?

Both companies have said that demand for EVs has been softening. Jim Farley, Ford’s CEO, acknowledged that “affordability is an issue” for consumers when it comes to EVs. Little surprise given that the company has significantly increased the price of its F-150 Lightning. Despite a recent price cut for certain models, the cheapest trim, which is targeted toward fleet customers, still lists for $10,000 more than when it was first announced.

For mainstream customers who thought they’d be able to snag a well-equipped, long-range electric truck for around $74,000 — about the average for an F-150 when accounting for tax credits — they quickly learned the price would actually be closer to $89,000. For those who don’t want a full-size truck, the average selling price of a Mustang Mach-E is nearly $60,000, according to Cox Automotive, well above the industry average. Little wonder people have begun to shy away from Ford’s electric offerings.

Ford and GM executives have also cited significant losses per vehicle as a reason why they’re slowing their EV rollout. Ford is “trying to find the balance between price, margin and EV demand,” Farley said. As evidence, the company said it lost an estimated $36,000 per EV last quarter.

It’s true that Ford would lose even more money if it cut prices further. But that’s how it works for new businesses, which is essentially what the EV divisions at these companies are. There’s a period of high investment and low revenue that leads to losses. Over time, though, the investment phase starts to pay off, and the company can start making up for its losses. It’s called the J curve, and it’s basically private equity’s entire sales pitch.

Automakers and their shareholders need to disabuse themselves of the notion that EVs will be profitable today or tomorrow or even a few years from now. Transitions take time. Yes, legacy car companies have significant resources they can draw on to help keep costs in line. But the EV transition is still radical enough that they can’t expect that expertise to make up the difference from day one.

Ford and GM only started warming to EVs after growing envious of Tesla’s skyrocketing share price. Reasonable people can argue about whether Tesla’s valuation is justified, but it was at least partly built on a decade of commitment to EVs. EVs are different enough from fossil-fuel vehicles that existing automakers are still in the learning phase. Ford and GM should have committed years ago when it was clear that EVs were no longer low-powered, short-range commuting appliances.

Imagine if Henry Ford had decided to take his foot off the gas. In the first two years of production, Ford sold about 30,000 Model Ts. At that time, horses were still the main form of transportation and demand for automobiles couldn’t have been less certain. But he stuck with it, and a decade later the company sold nearly 1 million Model Ts in a single year. Hemming and hawing over EVs may please shareholders today, but it almost certainly won’t a decade from now.