Update: The story has been updated to include comments from Capella Space CEO Payam Banazadeh and Phase Four. Paragraph five and six have been updated with additional context on solar flair activity and premature satellite reentry, and paragraph eleven contains additional information on Phase Four technology.

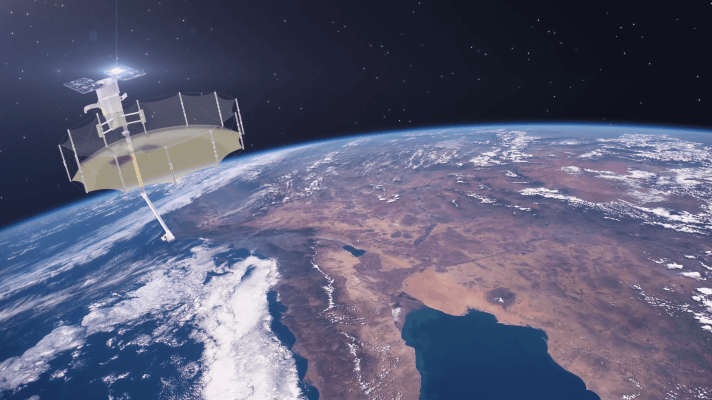

Capella Space’s synthetic aperture radar satellites are falling back to Earth much sooner than the three years they were anticipated to operate, according to publicly available satellite data.

The startup has launched a total of ten small satellites to low Earth orbit since 2018, including eight in its family of “Whitney”-class spacecraft. Five of these satellites have reentered the atmosphere since the end of January of this year, including three of the Whitneys. Those Whitney sats were in orbit for less than two-and-a-half years; one, Capella-5, was in orbit for less than two years.

That leaves five of the constellation in orbit, including the Capella-9 and Capella-10 launched on March 16, which are operating at an altitude of around 584 km and 588 km, respectively.

According to filings with the Federal Communication Commission, the propulsion system of Capella-9 was built by Phase Four. At least one of the satellites that has reentered prematurely, Capella-5, also used Phase Four propulsion. In that same filing from March 2022, Capella said its Capella-9 satellite would operate at an orbital altitude of 525 km, and maintain an altitude between 475-575 km for three years. It seems this is the typical mission profile of Capella satellites.

But Capella-7 and Capella-8, launched in January 2022, appear to be now operating below 400 kilometers, and will likely deorbit in a matter of weeks to a few months. The unexpected decay could be due to a problem with the propulsion system, a systematic miscalculation of its requirements, or other issues with the satellite performance unrelated to propulsion.

Solar activity in the Earth’s atmosphere has also ramped up; so-called ‘space weather’ can create issues for satellites, due to the increased atmospheric density and a higher number of solar events, like geomagnetic storms. According to NASA, we are ramping up to solar maximum, or the time in the solar cycle when sun’s activity peaks, which could take place in 2024 or 2025 (the full solar cycle began in 2019 and is anticipated to last through 2030). In general, this isn’t good for spacecraft; for example, in February 2022, SpaceX lost 40 Starlink satellites in one fell swoop due to a geomagnetic storm.

“The amount of solar activity in this new solar cycle is higher than anyone anticipated and atmospheric drag is affecting all LEO constellations,” said Steve Kiser, Phase Four board member, speaking on behalf of the company. “Phase Four and Capella Space enjoys a collaborative and cooperative partnership and we will continue to engage on how best to support their very important Earth Observation mission.”

“Probably they [Capella-7 and Capella-8] will reenter in Sep-Oct or so,” astronomer and analyst Jonathan McDowell said when reviewing the data at TechCrunch’s request. “I suspect propulsion failures but certainly it isn’t clear.”

In a statement to TechCrunch, Capella CEO Payam Banazadeh confirmed that some of the satellites have been deorbiting faster than expected “due to the combination of increased drag due to much higher solar activity than predicted by NOAA and less than expected performance from our 3rd party propulsion system.”

“We have upgraded our propulsion system on all future satellites to account for these facts, including the launch of our next generation satellite Acadia-1, currently scheduled for launch on August 5th 2023. We plan to launch eight of our next generation Acadia satellites over the next 12 months,” he added.

Late last month, Aviation Week reported that Phase Four has developed and tested a next-gen radio-frequency thruster for spacecraft that has hit performance parity or greater with a typical Hall-effect thruster, at decreased cost. It is unclear whether that thruster, which is called Maxwell Block 3, is the thruster that will be used on Capella’s Acadia satellites. TechCrunch has sent the inquiry to Banazadeh and will update the story with his response.

Seven year old Capella is one of a handful of startups building out constellations of synthetic aperture radar satellites in low Earth orbit, an imaging technique that allows for detailed 3D scans of the surface regardless of weather. In January, the company raised $60 million in funding, less than nine months after it closed a $97 million Series C. At the time, the company said the new capital would be used to build and launch the Acadia sats.

The first Acadia satellite will launch on board a Rocket Lab Electron rocket on August 6, the first of a multi-mission contract the two firms signed in February.

An independent report on orbital debris remediation prepared by NASA estimated each Capella satellite cost $5 million.