Monitoring service New Relic this morning said it has agreed to be acquired by Francisco Partners and TPG for $6.5 billion in cash.

Shares of the company, which went public back in 2014, are up around 13.5% on the news.

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

The deal is interesting because of its size, but we’re more interested in the insight it provides on the current state of the tech landscape as it pertains to valuations. Given the dry IPO climate, we are bereft of new data regarding exit values, so this deal is like a fresh, cool breeze on a sultry summer afternoon.

New Relic’s $87-per-share sale price gives it a valuation that’s less than seven times its current run-rate revenue. The question we have to answer is whether that price seems parsimonious, reasonable or indulgent given current market data and our valuation expectations based on recent private and public-market data.

New Relic’s $87-per-share sale price gives it a valuation that’s less than seven times its current run-rate revenue. The question we have to answer is whether that price seems parsimonious, reasonable or indulgent given current market data and our valuation expectations based on recent private and public-market data.

This morning, we’ll start with a look at New Relic’s latest quarterly results, compare that information to its sale price, and then relate what we’ve learned back to everyone’s favorite corporate cohort: richly valued startups that have yet to leave their parents’ basements.

A business based on consumption

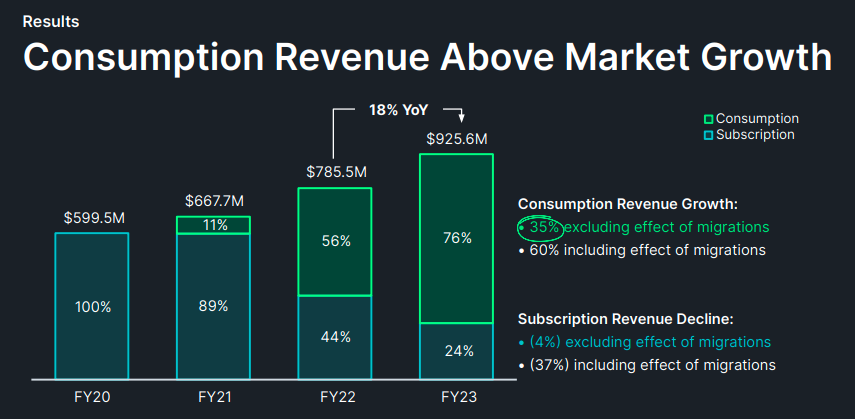

New Relic reported revenue of $242.6 million in the quarter ended June 30 (its fiscal first quarter), up 12% from a year earlier. The company has been shifting from a subscription model to a usage-based (consumption-based) pricing setup, and you can see that in the results: Consumption revenue increased 39% to $213.9 million, while subscription revenue declined by 54% to $28.7 million.

An investor deck from its Analyst Day in May details the company’s progress on the effort through the end of its fiscal 2023, which explains how it has changed its revenue mix:

Image Credits: New Relic

In Q1, consumption revenue accounted for just over 88% of New Relic’s total revenue, which means the company will soon be dependent almost entirely on usage-based revenue. The company’s gross margins also improved to 77.6%, up from 70.5% a year earlier.

However, New Relic still lost money: It recorded a $33 million operating loss (narrower than last year’s $55.7 million operating loss) and a similar net loss.

So the company is improving its profitability, sure, but it’s still far from breakeven in GAAP (generally accepted accounting principles) terms.

Still, New Relic is not lacking for cash. As it shared with its investors earlier today:

Trailing four quarter cash flows from operating activities was $89.1 million, compared to $36.8 million one year ago. Trailing four quarter free cash flow was $69.0 million, compared to $18.7 million one year ago.

In its Analyst Day presentation, New Relic pitched its new fiscal year as a period of “acceleration” and forecast more than 30% growth in consumption revenue and free cash flow of $150 million. So far, it is meeting that consumption revenue growth forecast and is making good progress toward its cash-flow goals.

Now all we have to do is answer this tiny, uncomplicated question: Just how much is a company like New Relic worth today? To save you from collecting the information needed to do the math: It is in a large, growing market; has annualized run-rate revenue of $970.4 million, growing at 12% a year; and has a trailing 12-month free cash flow of $69 million.

$6.5 billion

That’s 6.7x New Relic’s current run rate. In other words: Single-digit revenue multiples are all that’s within reach of unprofitable tech companies with growth rates in the low double digits and improving cash generation.

Going by today’s market standards, this is a reasonable figure. Altimeter’s Jamin Ball wrote last Friday that the median cloud software company has the following features:

- An enterprise value/NTM revenue multiple of 6.3x.

- 15% anticipated growth in the next year.

- 75% gross margins.

- A –20% operating margin.

- Free cash-flow margins of around 5%.

We already know New Relic’s exit multiple, its growth rates and its gross margins. Let’s sort out the last two numbers.

In its most recent quarter, New Relic reported GAAP operating margin of –13.6% and free cash-flow margin of around 30%, though we’d need to dive more into the seasonality of New Relic’s business before we can lean on that last metric.

New Relic is being bought at a time when it has better gross margins, operating margins, and cash generation than the median company of its size in today’s market. However, its revenue is expanding slower than the median rate for a company its size, which is perhaps the biggest reason it failed to command a bigger premium.

But what could New Relic do? Give up some profitability to chase a few more points of growth? If it did that, would investors have valued it more richly? Perhaps, but its improving cash generation is likely why private equity came knocking or why it managed to sell to its new owners at all.

Companies that spit out lots of cash — and can be squeezed for even more — can service a lot of debt, which means its owners can take huge chunks of cash out of their investment without sinking the business. If New Relic generated less cash, would it have been left alone?

In this case, it almost feels like we are looking at a median-ish public software company selling for a median-ish price in a boring market. There’s surprisingly little to learn here, apart from partly proving the argument that software companies are not great businesses. After all, impressive gross margins don’t mean that a software company will make money.