It’s no secret that the charging infrastructure for electric vehicles generally sucks.

There are exceptions, of course: Tesla has it pretty well figured out, and some highly trafficked corridors are well covered. But overall, the state of fast charging, which can replenish usable amounts of range in 30 minutes or less, isn’t great.

There are plenty of reasons why. Most chargers are located in massive parking lots, usually in a forgotten corner with little in the way of amenities for EV drivers. The equipment itself is notoriously unreliable, with one study suggesting that about a quarter of all Combined Charging System-compatible (CCS) stalls in the Bay Area are out of service at any given time. While charging speeds are increasing, most chargers aren’t nearly as fast as they need to be.

Some of those problems are easier to swallow than others. But one not mentioned above is a deal breaker: the dearth of available chargers. When they’re in short supply, EV drivers either struggle to find a spot or have to wait in line, sometimes for a while.

It’s widely accepted that Tesla’s Supercharger network is the best. It’s broadly distributed, the chargers are generally reliable, and most importantly, numerous.

That’s in part because Tesla’s fleet is the largest fully electric fleet in the U.S., with around 1.6 million vehicles on the road. It makes sense that their network is also the largest, with 17,551 stalls that charge at 120 kW or greater, according to data from the Department of Energy and Supercharger.info.

Image Credits: Miranda Halpern and Tim De Chant/TechCrunch

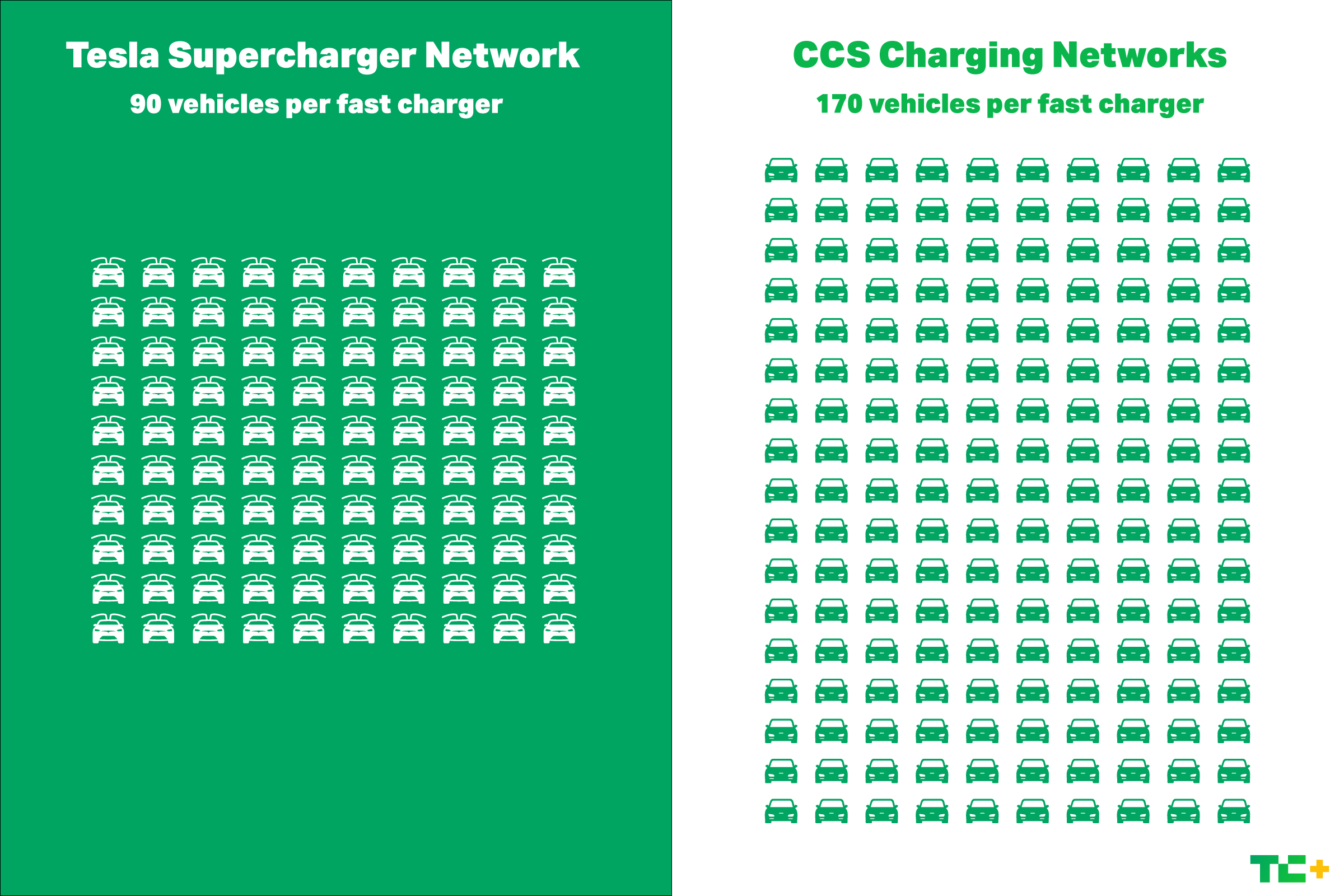

That’s just over 90 cars per stall. That ratio may not be perfect everywhere (some locations definitely need more chargers), but it seems about right overall.

On the other hand, there are far fewer non-Tesla electric vehicles in the U.S: At about 790,000 vehicles, it’s half the size. So in a sense, it’s logical that the charging network is about half the size as well, with 10,579 CCS ports.

But the reality is far worse. Those statistics include chargers that operate at wattages as low as 30 kW, which is hardly enough to count as fast charging. When considering chargers capable of 120 kW or more, the network shrinks by more than half: Just 4,643 CCS fast chargers fit the bill.

That means that each CCS fast-charging stall must serve 170 vehicles, about twice the number of a single Supercharger stall.

In the coming years, several CCS networks said they plan to install more chargers. EVgo has said it will add 3,250 fast chargers by the end of 2025. ChargePoint has said it will install 2,500 fast chargers as part of a deal with Mercedes. And Electrify America has a goal of operating 10,000 fast charging stalls by the end of 2025, up from about 3,500 today.

Altogether, that’s 12,250 new charging stalls a year and a half from now, bringing the leading non-Tesla networks up to where the Supercharger network is today. And Tesla isn’t standing still.

The task ahead is enormous. Tesla opening some of its chargers to other companies’ vehicles will ease the pain for Ford and GM drivers, but without rapid expansion of the Supercharger network, it’ll make Tesla drivers’ lives a little bit more miserable.

The situation is bleaker for everyone else. In a year and a half, there will be millions more EVs on the road, and the majority of them probably won’t be Teslas. Perhaps that’s what Ford and GM realized shortly before they signed their deals with Tesla. Charging networks may think they’re being ambitious with their targets, but the numbers suggest they’ll still fall drastically short of what’ll be needed.

If EV sales take off as expected — no reason why they won’t since they’ve already exceeded previous forecasts — there will be more than enough demand for a new charging network, one that maybe doesn’t just sell electricity and tries a different business model.

The EV transition is only beginning. There’s plenty of time to experiment.