While artificial intelligence long ago surpassed human capability in chess, and more recently Go — and let us not forget Doom — other more complex board games still present a challenge to computer systems. Until very recently, Stratego and Diplomacy were two of those games, but now AI has become table-flipping good at the former and passably human at the latter.

On the surface, you might think that it’s just because these games require a certain level of long-term planning and strategy. But so do Go and chess, just in a different way.

The crucial difference is actually that Stratego and Diplomacy are games of strategy based on imperfect information. In chess and Go, you can see every piece on the board. Stratego hides the identity of pieces until they are encountered by another piece, and Diplomacy is largely about establishing agreements, alliances and, of course, vendettas that are kept secret but are core to the gameplay. No honest chess game will involve a third party swooping in to protect your opponent’s bishop with a blue rook.

Both games require not raw calculation of paths to victory, but softer skills like guessing what the opponent is thinking, and what they think the computer is thinking, and make moves that accommodate and hopefully upset those assumptions. In other words, it has to bluff and convince another player of something, not just overpower it with the best possible moves.

The Stratego-playing model, from DeepMind, is named DeepNash, after the famous equilibrium. It is focused less on clever moves and more on play that can’t be exploited or predicted. In some cases this can be bold, like one game the team watched against a human player where the AI sacrificed several high-level pieces, leaving it at a material disadvantage — but it was all a calculated risk to bring out the other player’s big guns, so it could strategize around those. (It won.)

DeepNash is good enough that it beat other Stratego systems almost every time, and 84% of the time versus experienced humans. Because the algorithms that work well in Go and chess don’t work well here, they invented a new algorithmic method called Regularised Nash Dynamics — but you’ll have to read the paper if you want to understand it any more deeply than that. In the meantime, here’s an annotated game:

On the Diplomacy side, we have an AI named Cicero (ah, hubris!) from Meta and CSAIL that manages to play the game at a human level — and if that sounds like damning with faint praise, remember Diplomacy is difficult for most humans to play at a human level. The level of scheming, backstabbing, false promises and general Machiavellian antics that people get up to in the game are such that it is banned from many friendly gaming groups. Is a computer really capable of that level of shenanigans?

Seems so, and the advances that make it possible are interesting. After all, the interesting part of Diplomacy isn’t the world map and pieces, which are fairly straightforward to read and evaluate, but the potential for schemes latent in those arrangements. Is Venice being threatened on two fronts, or is it luring the western front into an envelopment through a long contemplated volte-face?

Not only that, but in order to participate in the scheming, one must speak (or chat, online) to other players and convince them of your sincerity and intent. This takes more than CPU cycles!

Image Credits: Meta

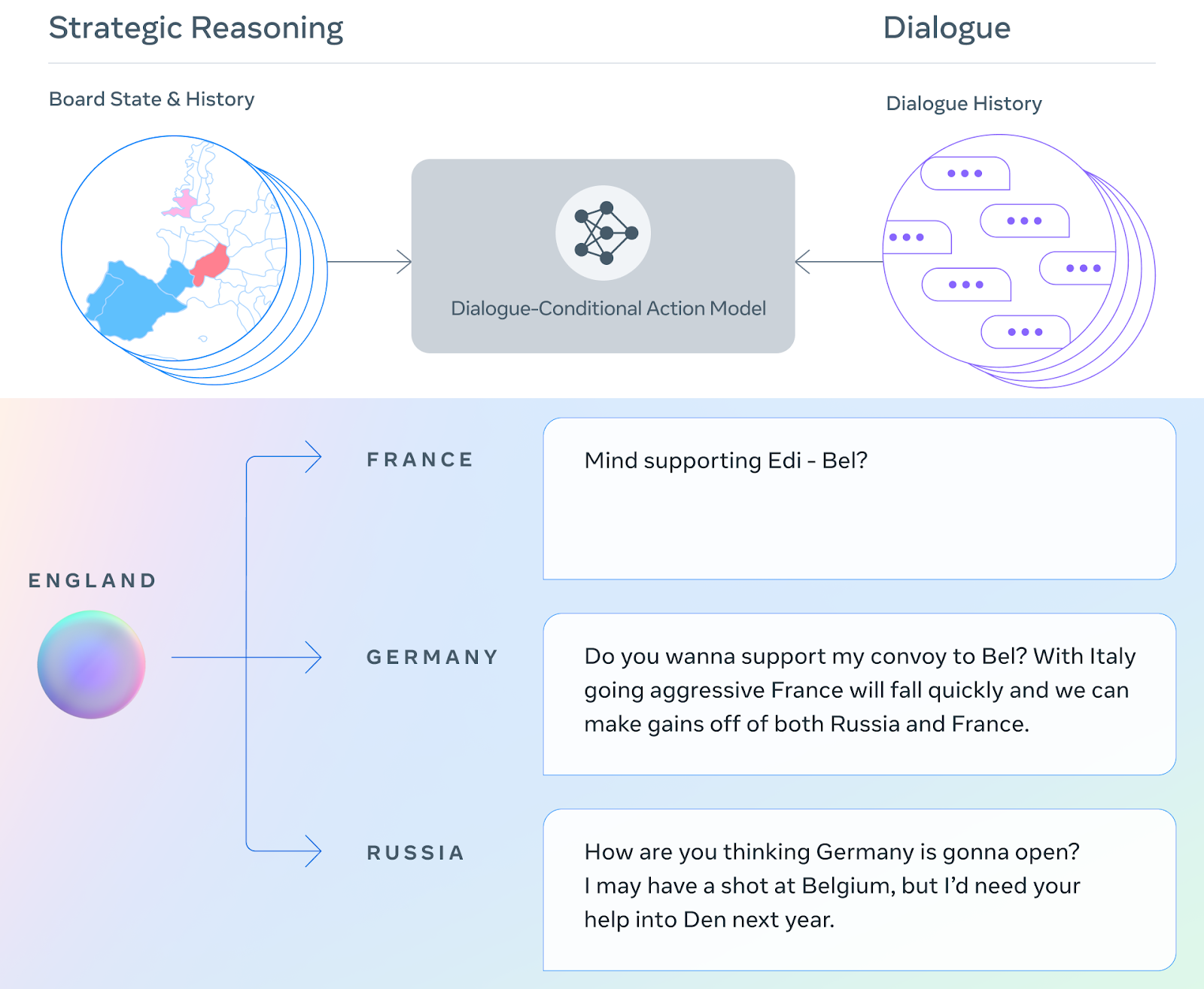

Here’s how Cicero works:

- Using the board state and current dialogue, make an initial prediction of what everyone will do.

- Refine that prediction using planning and then use those predictions to form an intent for itself and its partner.

- Generate several candidate messages based on the board state, dialogue and its intents.

- Filter the candidate message to reduce nonsense, maximize value and ensure consistency with our intents.

Then, plea your case and hope the other player isn’t planning your demise.

When set loose on webDiplomacy.net, Cicero played quite well against its opponents, placing 2nd out of 19 in a league and generally outscoring others.

It’s still very much a work in progress — it can lose track of what it’s said to others, or make other blunders humans probably wouldn’t — but it’s pretty remarkable that it can be competitive at all.