Why are software companies valuable? Put another way, why have we spent so many years valuing software companies using revenue multiples, instead of the profit multiples that are more common in other industries?

There are several key reasons. First, software companies have very strong gross margins; software is cheap to sell once you’ve written the code. Secondly, and more to the point today, is the fact that modern software companies are set up to sell more of their product to existing customers over time.

This is often achieved through selling more seats (individual use licenses) to extant accounts or, in the case of on-demand pricing, more total usage of a service over time. Regardless of the method, what matters is that software companies today tend to see limited gross churn (customers dropping their contracts) and positive net dollar retention (the sale of more product to existing customers over time).

The Exchange explores startups, markets and money.

Read it every morning on TechCrunch+ or get The Exchange newsletter every Saturday.

Net dollar retention (NDR) is, essentially, gross churn from existing customers plus upsells from the same, measured over a set time period. The resulting metric, measured in a percent of prior revenue, helps investors understand just how much built-in growth momentum a company has. The greater net dollar retention that a software company has, the more efficient its growth will be (selling more stuff to already-landed customers is cheaper than securing net-new accounts).

NDR matters, and investors, focused on more efficient growth than last year, are likely putting more emphasis on the metric. So, what should startups target when it comes to NDR results? Even more, do those expectations match what startups are actually reporting? And who has better net retention, public software companies or their startup rivals?

To find out, we’re dipping back into the recent OpenView-Chargebee SaaS benchmarks report to pull fresh data from operating startups, which we’ll contrast with norms and other reported results. The picture that forms is one in which the commentary and the on-the-ground reality are not the same.

To find out, we’re dipping back into the recent OpenView-Chargebee SaaS benchmarks report to pull fresh data from operating startups, which we’ll contrast with norms and other reported results. The picture that forms is one in which the commentary and the on-the-ground reality are not the same.

NDR in context

Given that NDR is a metric, we can establish what counts as good and not good for net retention results.

What is a good NDR result for a software company? Certainly something over 100%. You want churn to be more than overcome by upsells, effectively implying a growth rate for your company apart from newly landed accounts. The greater your NDR, the more natural growth momentum your software company has and the more durable your growth curve may prove, and you can infer greater return from newly landed customers, allowing more sales and marketing flexibility.

To set the stage a little, TechCrunch dug into results from Amplitude this quarter and spoke to Appian about its results. Looking at the data, Appian reported “cloud subscription revenue retention rate was 115% as of September 30, 2022.” Amplitude, in contrast, reported “dollar-based net retention rate was 123% as of September 30, 2022.”

That’s what two public software companies with billion-dollar-plus valuations reported in Q3 2022. What are other companies doing? Some are reporting far greater NDR results. Snowflake, perhaps the most richly valued public software company today by certain metrics, backs up its share price with “net revenue retention” of 171%. (There’s nuance to how companies calculate net retention, so we’re not trying to compare these companies per se, but instead to show a range of results to provide context for what startups are themselves reporting).

With some mature software companies reporting NDR results between 115% and 171%, startups should target a figure somewhere in between, yeah? Perhaps. There has been some noise — expectation, if we’re being bold — that startups should aim for 200% NDR results. But, the recent OpenView dataset implies that, in reality, NDR figures for startups at all stages of revenue growth (measured in ARR terms) are lower than we might have thought.

NDR at private companies

Talking to TechCrunch, OpenView noted that public companies are by definition the best of the best, and Snowflake is definitely an outlier. “Our benchmark data shows much [better] what’s more realistic in private market software companies,” operating partner Kyle Poyar said.

OpenView’s benchmarks data is broken down by annual revenue range. When it comes to NDR, that variable is surprisingly flat across ARR cohorts, barely moving from a median of 100% for startups with ARR below $1 million to 110% for companies with ARR above $50 million.

NDR also remained fairly consistent compared to 2021, with variations under 10 percentage points in any direction for each cohort. Perhaps even more tellingly, there isn’t that much difference between the bottom quartile and top performers, or when looking at companies by funding stage rather than by ARR range.

Then again, maybe none of these are the most relevant breakdown when it comes to NDR.

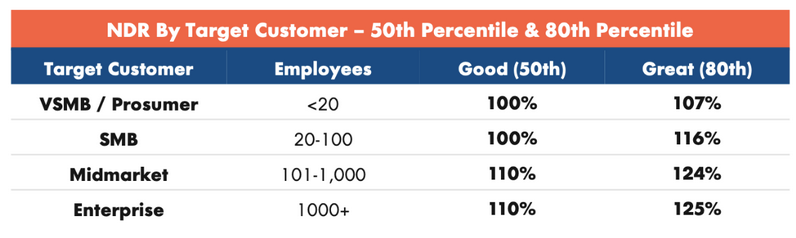

OpenView noted that more than other metrics, net dollar retention is “particularly sensitive to the type of customers you’re targeting.” Hence this graph, which splits companies based on their clients’ company size:

Image Credits: OpenView

From the above, it is pretty clear that the NDR of best-in-class SaaS startups is correlated to the size of their target customers. As OpenView observed, “opportunities for growth within an account are much higher at larger companies.” Some startups are clearly better at leveraging this than their average peers. But even then, we are talking about 125% not 200%.

Does it matter much, then, to have an NDR of 125% rather than 100%? Yes, it does. With more than 1,000 unicorns potentially in line to IPO, and no IPO in sight, it is more important than ever to show the kind of metrics that markets want to see. These days, that’s efficient growth, best illustrated by the Rule of 40.

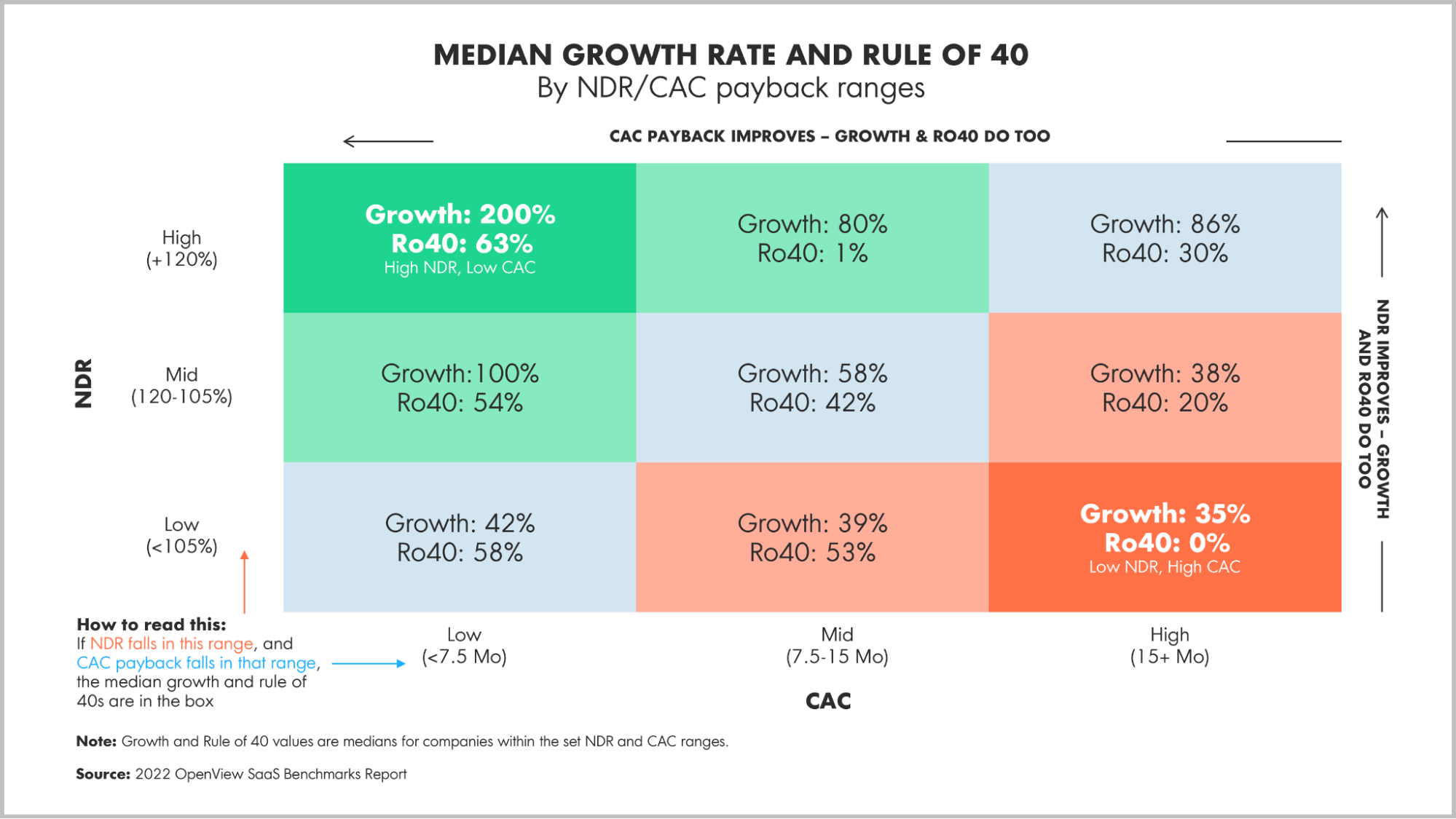

To both have outstanding growth and comply with the Rule of 40, it is necessary for SaaS companies to also have above-average NDR and a shorter CAC payback period, another metric that OpenView pays extra attention to. The graph below illustrates how this can pay off:

Image Credits: OpenView

It is not just OpenView that insists on these criteria, by the way. For instance, Battery Ventures’ recent State of the Open Cloud Report also stated that “high NDR is the cornerstone of efficiency and profitability.” However, what we found particularly interesting in OpenView’s report is that it also includes some advice on how to move the NDR needle.

Moving the NDR needle

Net dollar retention is sometimes thought of as an immovable object because it is heavily dependent on the type of customers a company is targeting and because a great NDR reflects a product that customers can’t get enough of — and that’s obviously hard to achieve.

Commenting on options a founder might consider, Poyar noted that there are not very many things a company can do to meaningfully improve their NDR, “especially in the near term.”

“It takes a while to build products or find new products that you can sell into your customer base,” the VC said. “You could build out a new go-to-market motion to put more emphasis on a cross-sell upsell, maybe even add dedicated teams that work on that; but [there are] additional headcount, additional costs associated with sales compensation and new motions that you don’t know whether they’re going to be effective.”

This inspired OpenView’s recommendation: That pricing, rather than expanding one’s product mix, is the lever founders should focus on to improve their NDR. Poyar’s co-author, Curt Townshend, explained that this variable is a “simple” way to try to expand customers. While it is not immediate, either, it has clearer short-term impact than other options.

It is worth noting that improved pricing doesn’t translate as “charging more.” Rather, it means finding the pricing model that will drive more revenue overall. This can mean trying new approaches, Poyar said: “We see a number of companies looking at ways to experiment with some sort of either usage-based model or ‘hybrid subscription plus usage’ in order to have that expansion path with their customers.”

Abandoning traditional pricing may seem like a paradox, as charging for more seats seems like a straightforward way to expand revenue. But expanding based on consumption is equally valid, and perhaps stickier, because it reflects consumer demand more accurately. This could explain why more SaaS companies are shifting to usage-based pricing.

This gives us two key metrics to track in Q4 earnings, when they come early next year: Beyond the usual growth percentages and revenue tallies, we will keep close tabs on NDR and Rule of 40 data, and we will also check whether usage-based pricing remains on the rise.