The European Commission is facing fresh calls to make good on its 2017 antitrust decision against Google Shopping by banning Google from displaying its own shopping comparison ads units in search results — boxes which Google populates with revenue-generating ads — as they argue the self-preferencing units constitute an ongoing competition abuse by the adtech giant.

The 2017 Commission decision found Google abused its dominance by systematically giving prominent placement to its own comparison shopping service and demoting rival comparison shopping services in search results.

Google was left to devise its own remedy to comply with the order to cease infringing the bloc’s competition rules and rivals have continued to complain there is still no level playing field for shopping comparison services trying to reach consumers via Google’s dominant search channel.

Yesterday Reuters reported that more than 40 rival comparison shopping services (CSS) operating across Europe — including Kelkoo, PriceRunner and idealo — had written to Commission EVP, Margrethe Vestager, accusing Google of continued noncompliance with the 2017 EU order.

The companies are calling for the Commission to step in and close down Google’s Shopping Units — arguing that the mechanism it devised following the original antitrust decision “allow[s] no competition” and leads to “higher prices and less choice for consumers,” as well as enabling what they describe as an “unfair transfer of profits” to Google.

“Today, there is clear evidence that Google’s chosen mechanism to comply with the Google Search (Shopping) decision is both economically ineffective and legally insufficient,” they add.

In a letter that stretches over seven pages, which TechCrunch has reviewed, the CSS also make a case for the Commission to act against Google’s self-preferencing ahead of the incoming EU Digital Markets Act (DMA) — which will bring in an up-front ban on self-preferencing by the most powerful intermediating platforms (so-called “gatekeepers”), starting next year — arguing that “Google’s prominent embedding of Shopping Units is a prima facie infringement of the DMA’s ban on self-preferencing.”

Google is widely expected to be designated a gatekeeper, and Google search a core platform service, under the DMA when the regime starts operating in 2023 — although it’s not clear how quickly these designations will happen (months at least will be required).

Evidently, the 40+ CSS are tired of hanging around waiting for the Commission to enforce a level playing field for shopping comparison services after five years of being frustrated by Google’s self-interested shaping of product search results.

Last November, the tech giant’s appeal against the 2017 EU decision was largely dismissed by the General Court that also made a critical assessment of its use of Shopping Units that it said depended on comparison shopping services changing their business model and “ceasing to be Google’s direct competitors, becoming its customers instead.”

While an investigation by Sky News, back in 2018, accused Google of trying to circumvent the EU antitrust ruling by offering incentives to ad agencies to create faux comparison sites filled with ads for their clients’ products which Google could display in the Shopping Units to present the impression of a thriving marketplace for price comparison services.

Separately, PriceRunner announced a competition lawsuit against Google earlier this year — seeking €2.1 billion in damages for what it alleges is continued noncompliance of the 2017 Google Shopping decision.

“Our industry has been stalled by Google’s confirmed abuse and the subsequent non-compliance for over 13 years. The Commission needs to re-open space on general search results pages for the most relevant providers, by removing Google’s Shopping Units that allow no competition but lead to higher prices and less choice for consumers and an unfair transfer of profit margins from merchants and competing CSSs to Google,” the CSS write in their letter to the Commission now.

“We have patiently waited for the General Court’s endorsement of the Shopping decision and the DMA’s ban on self-preferencing and assisted you along the way. Considering the unambiguous new legal framework, it is now time to walk the talk. The most paramount case at the heart of the calls for the DMA needs to be brought to an effective end. We have weighed up all alternative solutions but came to agree with Recital (51) DMA: the only effective end is that Google no longer displays groups of specialised search results that enable the comparison of products and prices directly within Google’s general results pages. Shopping Units need to go.”

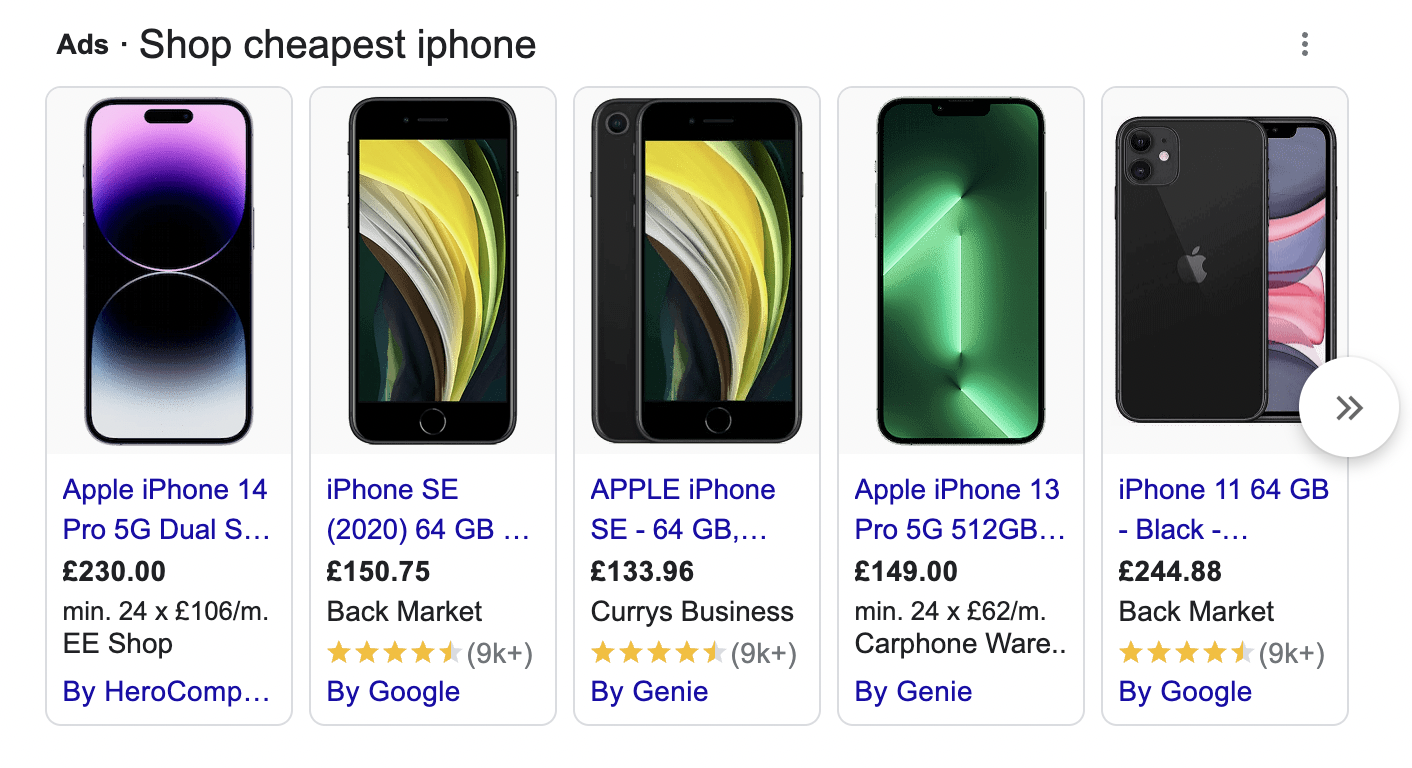

The disputed Shopping Units appear in Google search results in response to certain types of product search — such as the below example generated by a search for “cheapest iPhone” — and may link users to rival comparison services. However third parties must bid to win slots in the ad units, which means that if a CSS is successful in a Shopping Unit ad auction it is paying Google to appear in an advertisement that it typically locates at the top of search results, above organic results where shopping comparison services might otherwise be displayed more prominently on the merits of their utility.

Image Credits: (screengrab) Natasha Lomas/TechCrunch

The CSS argue that Google’s mechanism is skewed against genuine produce comparison services — favoring ad resellers that do not compete directly with Google in comparison shopping search.

“Empirical data confirms that Google’s mechanism requires a market exit. According to a study of over one million Shopping Units in Summer 2022, ‘93% of Google Shopping ads in Shopping Units are published by just the top 20 [Google] CSS partners’. Yet ‘the top 20 CSS partners only account for 1.4% of organic search results for the dataset.’ This is ‘because these CSS partners primarily facilitate Google Shopping Units — they don’t offer an online product comparison service themselves’,” they write.

“Put differently, today 93% of the offers in Shopping Units originate from companies that do not compete with Google on any relevant market for comparison shopping services but that have become mere resellers of Google Shopping Ads which they buy at a marginal profit on behalf of merchants. Shopping Units thus continue to constitute a Google-own CSS that is favoured within general search results pages.”

Google injects Shopping Units into search results for many types of products and services, from price comparison-focused electronic gadgetry to vacation accommodation, travel and jobs — and the CSS go on to suggest in their letter that players across other verticals “share our concerns and equally call for an end of Google’s boxes,” adding: “Enforcing compliance with the Shopping remedy will thus have an impact far beyond markets for comparison shopping. Conversely, any failure to act resolutely would only invite even more abuses of dominance.”

An auction mechanism Google devised following another Commission antitrust decision — back in 2018, against its Android smartphone platform — which saw rival search engines being required to bid in a paid Google auction to appear in a regional ‘choice screen’ on Android devices was similarly criticized — for years — as self-serving faux compliance by Google (and an ongoing failure of EU antitrust enforcement).

In that case the Commission did ultimately step in, last year, forcing Google to revise its approach by ditching the paid auction and displaying a selection of rival search engines that’s free for eligible participants, largely based on popularity per market. But search rivals remain critical of flagrant under-enforcement by the EU which allowed Google to devise and deploy a self-interested mechanism that led to — at the very least — years of delay during which there has been no meaningful reduction in its search marketshare.

As the DMA comes into application next year, the Commission will be taking on an expanded enforcement role for competition rules that absolutely demands a contrastingly pro-active approach — so the change of gear that will be required is huge. And there are already concerns that the EU’s executive will fumble the responsibility of effectively policing Big Tech, leaving consumer and businesses to continue to suffer from tipped digital markets.

The Commission was contacted for a response to the CSS’ letter — and to their call for an end to Google’s Shopping Units — but at press time it had not provided any comment.

Update: A Commission spokeswoman confirmed it has received the letter and said it will respond “in due course,”adding: “We continue to carefully monitor the market with a view to assessing the effectiveness of the remedies.”

On the DMA, the spokeswoman said the Commission intends to organize “a number of technical workshops with interested stakeholders to gauge third-party views on compliance with gatekeepers’ obligations under the DMA.”

“The view of third parties, in particular those who are potential beneficiaries of the DMA’s obligations, will be essential in ensuring practicable and effective compliance of gatekeeper so as to achieve the goals of the DMA,” she said, adding: “We expect that the first of such technical workshops could take place by the end of the year/beginning of next year.”

In further remarks on “uptake” of Google’s remedy, the Commission spokeswoman noted that the rate of display of offers from competitors of Google make up “approximately 75% of total inventory of Shopping Units.”

“About 90% of the Shopping Unit displayed by Google have at least one offer from competitors of Google. About half of the clicks within Shopping Units are on offers from competitors of Google,” she added.

Asked for its response to the letter, a Google spokeswoman pointed us back to an earlier blog post, from March 2022, in which it claims Shopping Ads “support jobs and business growth in Europe” — while enabling shoppers to “quickly and easily find your merchants’ online inventory,” as it tells it.

“People find these results helpful and traffic to these ads has continuously increased over time (in 2021, consumers clicked on 30% more shopping ads from CSSs than in 2020). And almost all CSSs have increased the number of merchants they work with or increased their activity with existing merchants,” Google further claimed in the blog post, adding that the number of CSS businesses advertising on Google grew by more than 20% in 2021.

“In total, there were more than 350 active Comparison Shopping Services groups in Europe who advertise on shopping ads at the end of 2021. Together, they operate more than 800 CSS websites across multiple countries in Europe, creating new business opportunities and job growth,” it also wrote.

In their letter to the Commission, the CSS references the General Court’s judgment from last year — which they argue “clarified that equal treatment within search results pages is more than equal treatment within any element of a page such as Shopping Units.”

“The General Court listed several factors that Google needs to fulfil to treat rivals equally. Inter alia, it found that Shopping Units constitute a Google CSS in themselves that directly compete with rival CSSs and that the ability for CSSs to ‘participate’ in such units by bidding for ads within them entails no equal treatment. Google has not changed this mechanism after the decision and therefore does not fulfil the Court’s require,” they explain.

“The General Court also shuttered the only argument that we have ever heard in favour of the mechanism Google chose to adopt, namely that by now over 90% of the Shopping Units displayed contain at least one product ad (offer) that was served by a rival service. The Court clarified that ‘there is nothing in the contested decision to suggest that the Commission, ultimately, indirectly approved the method of integrating ads from competing [CSSs] in the Shopping Units.’ The Court itself rejected the mechanism that Google still uses today because to appear in Shopping Units requires rivals ‘to become customers of Google’s comparison shopping service and stop being its direct competitors’.”

The letter also highlights how much money Google generates from Shopping Units.

“While useless for rivals, Google’s ‘compliance mechanism’ is highly profitable for Google. ‘Rival ads’ were the biggest driver for tripling Google’s search advertising revenues from USD 89 billion in 2016 to USD 257 billion in year 2021. Consumers had to pay the price: Studies repeatedly found that Shopping Units recommend more expensive products than genuine CSSs would, causing overpayments in the billions,” they argue.

“This is thanks, not despite, the ‘compliance mechanism.’ That the Turkish and the South African competition authorities denounced Google’s chosen ‘compliance mechanism’ as ineffective and counter-productive, came as no surprise but confirms our position.”

The letter also rebuts Google’s suggestion of “alleged advantages of Shopping Units for consumers or merchants” and points out that the “per-se ban in Art. 6(5) DMA of any ’embedding’ of a separate service, such as a CSS, within search results pages, leaves no room for any justification” (i.e., based on such claimed advantages).

They also note the General Court’s skepticism that Google’s conduct could generate “efficiency gains by improving the user experience” — as well as highlighting its view that “those efficiency gains, assuming they exist, do not appear in any way to be likely to counteract the significant actual or potential anticompetitive effects generated by those practices”.

Nor, the CSS argue, would enforcing a ban on Google’s self-preferencing require a return to a basic “10 blue links” being displayed in search results as they say “Google has falsely claimed” — suggesting it’s offering a false choice between self-serving self-preferencing or an intentionally degraded search experience.

“There are no technical limits to ensure an equal treatment of CSSs without reducing the quality of general search results pages for consumers and merchants,” they argue. “An end of Google’s self-serving Shopping Units would not necessitate an end of product images and or other enriched formats that Google considers helpful for consumers, as long as Google does not use such features to provide a price and product comparison service directly within its general search results pages (thereby embedding its own CSS). Conversely, the positive reactions of consumers and merchants in countries without Shopping Units suggest that an end of such units would pave the way for more innovation and competition in the markets for comparison shopping services, which, by definition, are of high significance for consumer welfare as they promote and encourage low product prices.”